6. Information Gathering

The goal of a penetration test (or pentest) is to detect security gaps to improve the defenses of the company being tested. Because the network, devices, and software within the company's environment change over time, penetration testing is a cyclic activity. A company's attack surface changes periodically due to newly discovered software vulnerabilities, configuration mistakes from internal activities, or IT restructuring that might expose new segments for targeting.

In this Learning Module, we'll learn how to methodically map such an attack surface using both passive and active means, and understand how to leverage this information during the entire penetration test lifecycle.

6.1. The Penetration Testing Lifecycle

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objectives:

- Understand the stages of a Penetration Test

- Learn the role of Information Gathering inside each stage

- Understand the differences between Active and Passive Information Gathering

To keep a company's security posture as tightly controlled as possible, we should conduct penetration testing on a regular cadence and after every time there's a significant shift in the target's IT architecture.

A typical penetration test comprises the following stages:

- Defining the Scope

- Information Gathering

- Vulnerability Detection

- Initial Foothold

- Privilege Escalation

- Lateral Movement

- Reporting/Analysis

- Lessons Learned/Remediation

In this Module, we'll briefly cover scoping before turning our focus to the main objective, Information Gathering. We will learn more about the other stages during the rest of the course.

The scope of a penetration test engagement defines which IP ranges, hosts, and applications should be test subjects during the engagement, as compared to out-of-scope items that should not be tested.

Once we have agreed with the client on the engagement's scope and time frame, we can proceed to the second step, information gathering. During this step, we aim to collect as much data about the target as possible.

To begin information gathering, we typically perform reconnaissance to retrieve details about the target organization's infrastructure, assets, and personnel. This can be done either passively or actively. While the former technique aims to retrieve the target's information with almost no direct interaction, the latter probes the infrastructure directly. Active information gathering reveals a bigger footprint, so it is often preferred to avoid exposure by gathering information passively.

It's important to note that information gathering (also known as enumeration) does not end after our initial reconnaissance. We'll need to continue collecting data as the penetration test progresses, building our knowledge of the target's attack surface as we discover new information by gaining a foothold or moving laterally.

In this Module, we'll first learn about passive reconnaissance, then explore how to actively interact with a target for enumeration purposes.

6.2. Passive Information Gathering

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objectives:

- Understand the two different Passive Information Gathering approaches

- Learn about Open Source Intelligence (OSINT)

- Understand Web Server and DNS passive information gathering

Passive Information Gathering, also known as Open-source Intelligence (OSINT), is the process of collecting openly-available information about a target, generally without any direct interaction with that target.

Before we begin, we need examine the two different schools of thought about what constitutes "passive" in this context.

In the strictest interpretation, we never communicate with the target directly. For example, we could rely on third parties for information, but we wouldn't access any of the target's systems or servers. Using this approach maintains a high level of secrecy about our actions and intentions, but can also be cumbersome and may limit our results.

In a looser interpretation, we might interact with the target, but only as a normal internet user would. For example, if the target's website allows us to register for an account, we could do that. However, we would not test the website for vulnerabilities during this phase.

Both approaches can be useful, depending on the objectives of the test we are conducting. For this reason, we need to consider the scope and rules of engagement for our penetration test before deciding which to use.

In this Module, we will adopt this latter, less rigid interpretation for our approach.

There are a variety of resources and tools we can use to gather information, and the process is cyclical rather than linear. In other words, the "next step" of any stage of the process depends on what we find during the previous steps, creating "cycles" of processes. Since each tool or resource can generate any number of varied results, it can be hard to define a standardized process. The ultimate goal of passive information gathering is to obtain information that clarifies or expands an attack surface, helps us conduct a successful phishing campaign, or supplements other penetration testing steps such as password guessing, which can ultimately lead to account compromise.

Instead of demonstrating linked scenarios, we will simply cover various resources and tools, explain how they work, and arm you with the basic techniques required to build a passive information gathering campaign.

Before we begin discussing resources and tools, let's share a personal example of a penetration test that involved successful elements of a passive information gathering campaign.

A Note From the Authors

Several years ago, the team at OffSec was tasked with performing a penetration test for a small company. This company had virtually no internet presence and very few externally-exposed services, all of which proved to be secure. There was practically no attack surface to be found. After a focused passive information gathering campaign that leveraged various Google search operators, connected bits of information "piped" into other online tools, and a bit of creative and logical thinking, we found a forum post made by one of the target's employees in a stamp-collecting forum:

Hi!

I'm looking for rare stamps from the 1950's - for sale or trade.

Please contact me at david@company-address.com

Cell: 999-999-9999

We used this information to launch a semi-sophisticated client-side attack. We quickly registered a stamps-related domain name and designed a landing page that displayed various rare stamps from the 1950's, which we found using Google Images. The domain name and design of the site definitely increased the perceived reliability of our stamp trading website.

Next, we embedded some nasty client-side attack exploit code in the site's web pages, and called "David" during the workday. During the call, we posed as a stamp collector that had inherited their Grandfather's huge stamp collection.

David was overjoyed to receive our call and visited the malicious website to review the "stamp collection" without hesitation. While browsing the site, the exploit code executed on his local machine and sent us a reverse shell.

This is a good example of how some innocuous passively-gathered information, such as an employee engaging in personal business with his corporate email, can lead to a foothold during a penetration test. Sometimes the smallest details can be the most important.

Warning

While "David" wasn't following best practices, it was the company's policy and lack of a security awareness program that set the stage for this breach. Because of this, we avoid casting blame on an individual in a written report. Our goal as penetration testers is to improve the security of our client's resources, not to target a single employee. Simply removing "David" wouldn't have solved the problem.

Let's review some of the most popular tools and techniques that can help us conduct a successful information gathering campaign. We will use MegaCorp One, a fictional company created by OffSec, as the subject of our campaign.

6.2.1. Whois Enumeration

Whois is a TCP service, tool, and type of database that can provide information about a domain name, such as the name server and registrar. This information is often public, since registrars charge a fee for private registration.

We can gather basic information about a domain name by executing a standard forward search and passing the domain name, megacorpone.com, into whois, providing the IP address of our Ubuntu WHOIS server as an argument of the host (-h) parameter.

kali@kali:~$ whois megacorpone.com -h 192.168.50.251

Domain Name: MEGACORPONE.COM

Registry Domain ID: 1775445745_DOMAIN_COM-VRSN

Registrar WHOIS Server: whois.gandi.net

Registrar URL: http://www.gandi.net

Updated Date: 2019-01-01T09:45:03Z

Creation Date: 2013-01-22T23:01:00Z

Registry Expiry Date: 2023-01-22T23:01:00Z

...

Registry Registrant ID:

Registrant Name: Alan Grofield

Registrant Organization: MegaCorpOne

Registrant Street: 2 Old Mill St

Registrant City: Rachel

Registrant State/Province: Nevada

Registrant Postal Code: 89001

Registrant Country: US

Registrant Phone: +1.9038836342

...

Registry Admin ID:

Admin Name: Alan Grofield

Admin Organization: MegaCorpOne

Admin Street: 2 Old Mill St

Admin City: Rachel

Admin State/Province: Nevada

Admin Postal Code: 89001

Admin Country: US

Admin Phone: +1.9038836342

...

Registry Tech ID:

Tech Name: Alan Grofield

Tech Organization: MegaCorpOne

Tech Street: 2 Old Mill St

Tech City: Rachel

Tech State/Province: Nevada

Tech Postal Code: 89001

Tech Country: US

Tech Phone: +1.9038836342

...

Name Server: NS1.MEGACORPONE.COM

Name Server: NS2.MEGACORPONE.COM

Name Server: NS3.MEGACORPONE.COM

...

Not all of this data is useful, but we did discover some valuable information. First, the output reveals that Alan Grofield registered the domain name. According to the Megacorp One Contact page, Alan is the "IT and Security Director".

We also found the name servers for MegaCorp One. Name servers are a component of DNS that we won't be examining now, but we should nevertheless add these servers to our notes.

Assuming we have an IP address, we can also use the whois client to perform a reverse lookup and gather more information.

kali@kali:~$ whois 38.100.193.70 -h 192.168.50.251

...

NetRange: 38.0.0.0 - 38.255.255.255

CIDR: 38.0.0.0/8

NetName: COGENT-A

...

OrgName: PSINet, Inc.

OrgId: PSI

Address: 2450 N Street NW

City: Washington

StateProv: DC

PostalCode: 20037

Country: US

RegDate:

Updated: 2015-06-04

...

The results of the reverse lookup give us information about who is hosting the IP address. This information could be useful later, and as with all the information we gather, we will add this to our notes.

6.2.2. Google Hacking

The term "Google Hacking" was popularized by Johnny Long in 2001. Through several talks and an extremely popular book (Google Hacking for Penetration Testers), he outlined how search engines like Google could be used to uncover critical information, vulnerabilities, and misconfigured websites.

At the heart of this technique is using clever search strings and operators for the creative refinement of search queries, most of which work with a variety of search engines. The process is iterative, beginning with a broad search, which is narrowed using operators to sift out irrelevant or uninteresting results.

We'll start by introducing several of these operators to learn how they can be used.

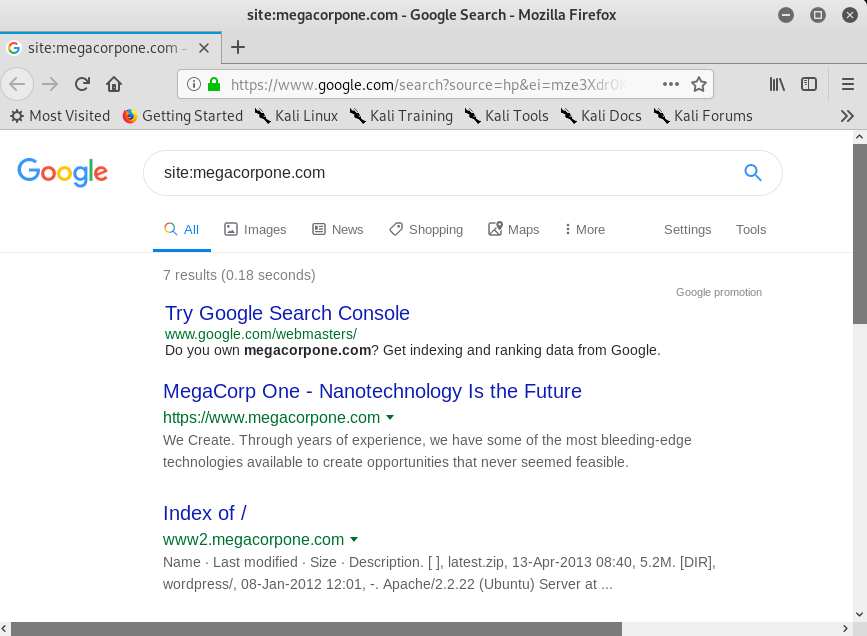

The site operator limits searches to a single domain. We can use this operator to gather a rough idea of an organization's web presence.

Figure 1: Searching with a Site Operator

The image above shows how the site operator limited the search to the megacorpone.com domain we have specified.

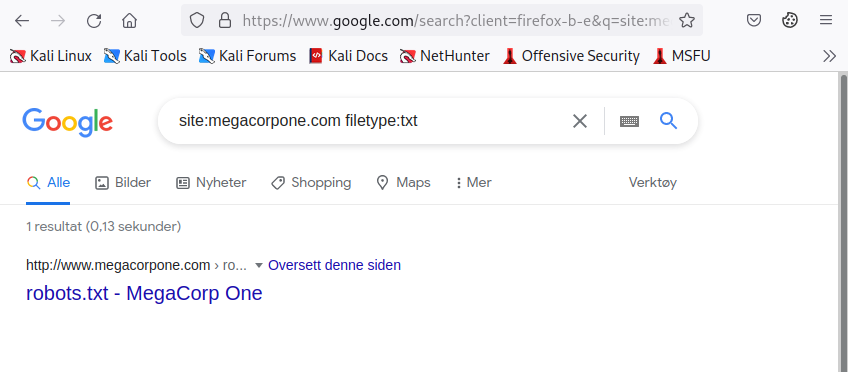

We can then use further operators to narrow these results. For example, the filetype (or ext) operator limits search results to the specified file type.

In the example below, we combine operators to locate TXT files (filetype:txt) on www.megacorpone.com (site:megacorpone.com):

Figure 2: Searching with a Filetype Operator

We receive an interesting result. Our query found the robots.txt file, containing following content.

Listing 4 - robots.txt fileThe robots.txt file instructs web crawlers, such as Google's search engine crawler, to allow or disallow specific resources. In this case, it revealed a specific PHP page (/nanities.php) that was otherwise hidden from the regular search, despite being listed allowed by the policy.

The ext operator could also be helpful to discern which programming languages might be used on a web site. Searches like ext:php, ext:xml, and ext:py will find indexed PHP Pages, XML, and Python pages, respectively.

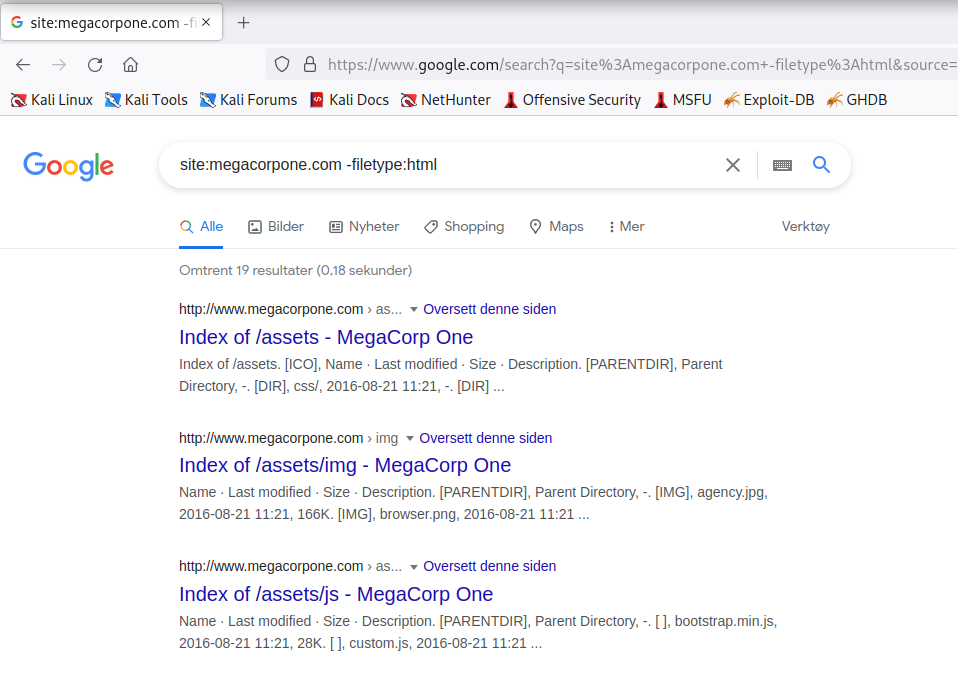

We can also modify an operator using - to exclude particular items from a search, narrowing the results.

For example, to find interesting non-HTML pages, we can use site:megacorpone.com to limit the search to megacorpone.com and subdomains, followed by -filetype:html to exclude HTML pages from the results.

Figure 3: Searching with the Exclude Operator

In this case, we found several interesting pages, including web directories indices.

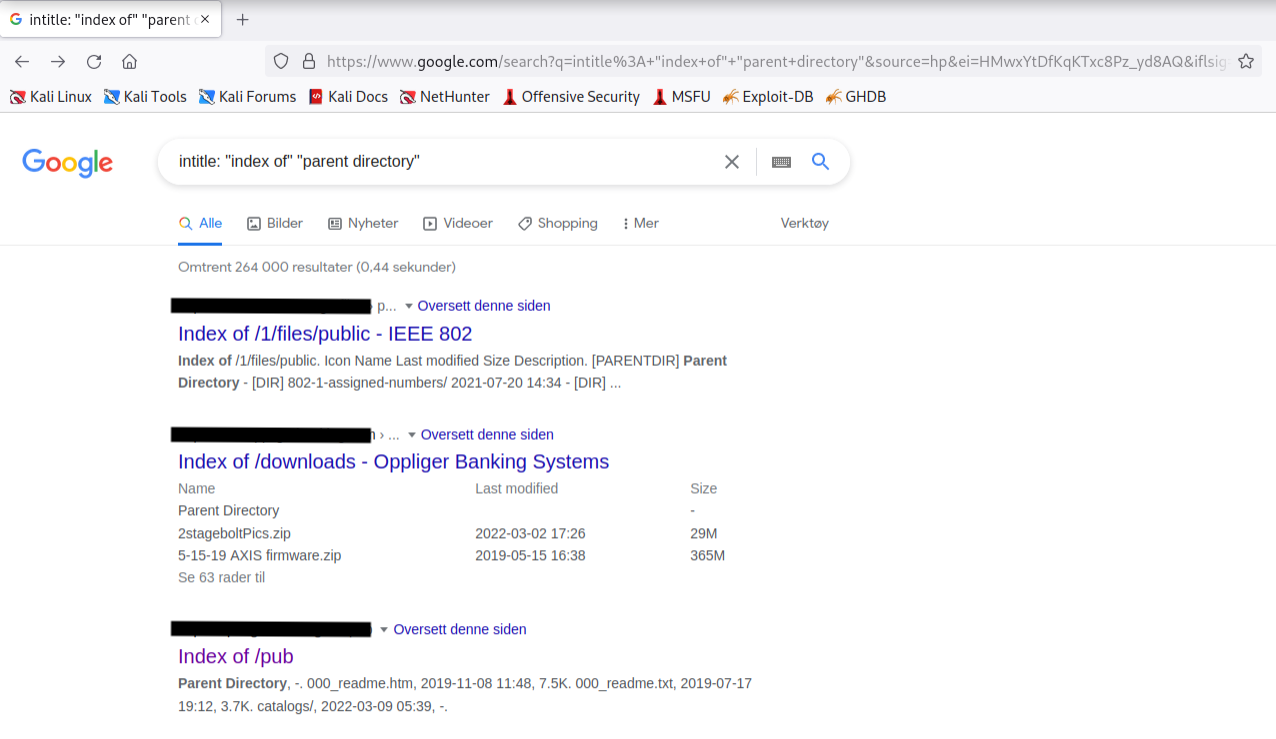

In another example, we can use a search for intitle:"index of" "parent directory" to find pages that contain "index of" in the title and the words "parent directory" on the page.

Figure 4: Using Google to Find Directory Listings

The output refers to directory listing pages that list the file contents of the directories without index pages. Misconfigurations like this can reveal interesting files and sensitive information.

These basic examples only scratch the surface of what we can do with search operators. The Google Hacking Database (GHDB) contains multitudes of creative searches that demonstrate the power of leveraging combined operators.

Figure 5: The Google Hacking Database (GHDB)

Another way of experimenting with Google Dorks is through the DorkSearch portal, which provides a pre-built subset of queries and a builder tool to facilitate the search.

Mastery of these operators, combined with a keen sense of deduction, are key skills for effective search engine "hacking".

6.2.3. Netcraft

Netcraft is an internet service company, based in England, offering a free web portal that performs various information gathering functions such as discovering which technologies are running on a given website and finding which other hosts share the same IP netblock.

Using services such as Netcraft is considered a passive technique, since we never directly interact with our target.

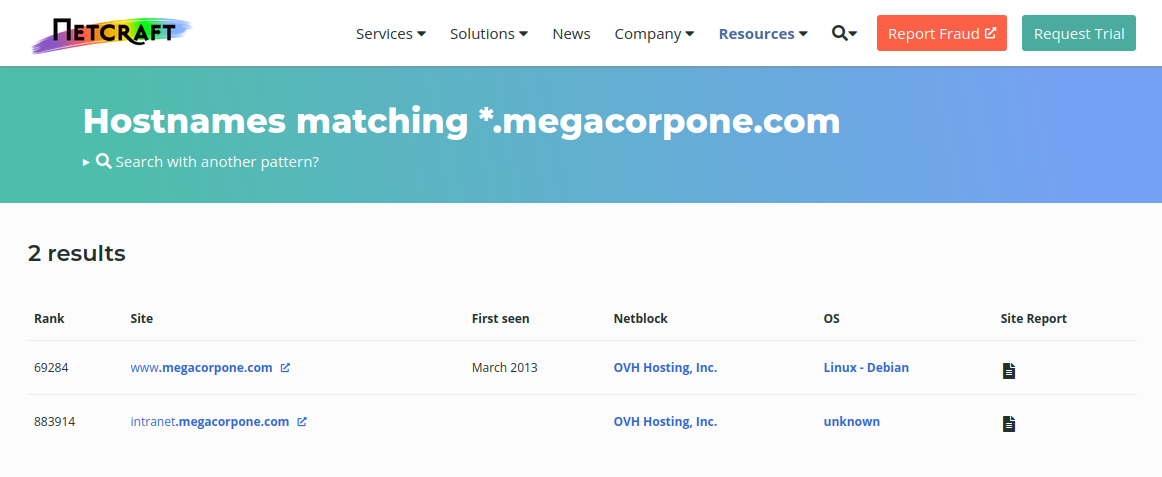

Let's review some of Netcraft's capabilities. For example, we can use Netcraft's DNS search page to gather information about the megacorpone.com domain:

Figure 6: Netcraft Results for *.megacorpone.com Search

For each server found, we can view a "site report" that provides additional information and history about the server by clicking on the file icon next to each site URL.

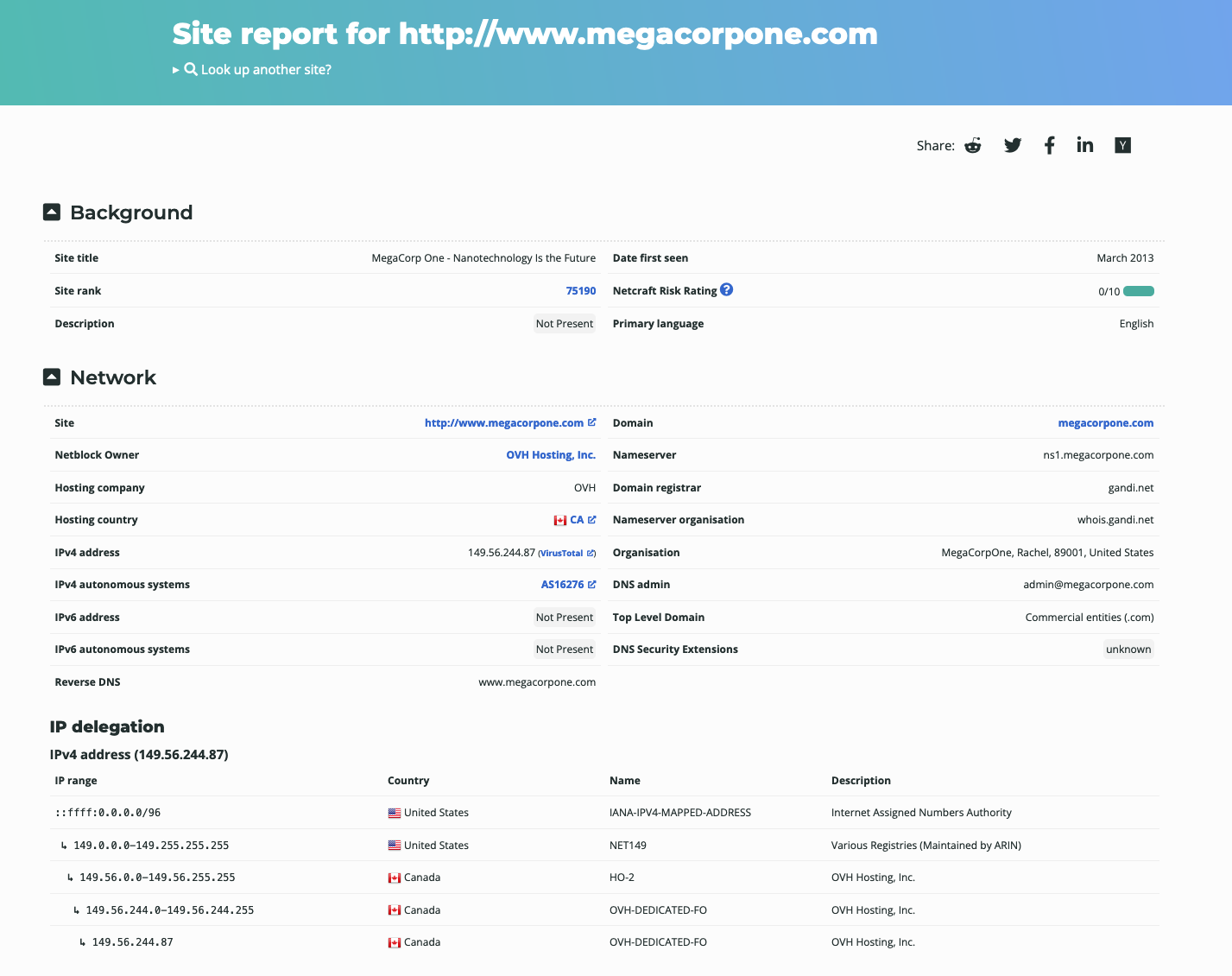

Figure 7: Netcraft Site Report for www.megacorpone.com

The start of the report covers registration information. However, if we scroll down, we discover various "site technology" entries.

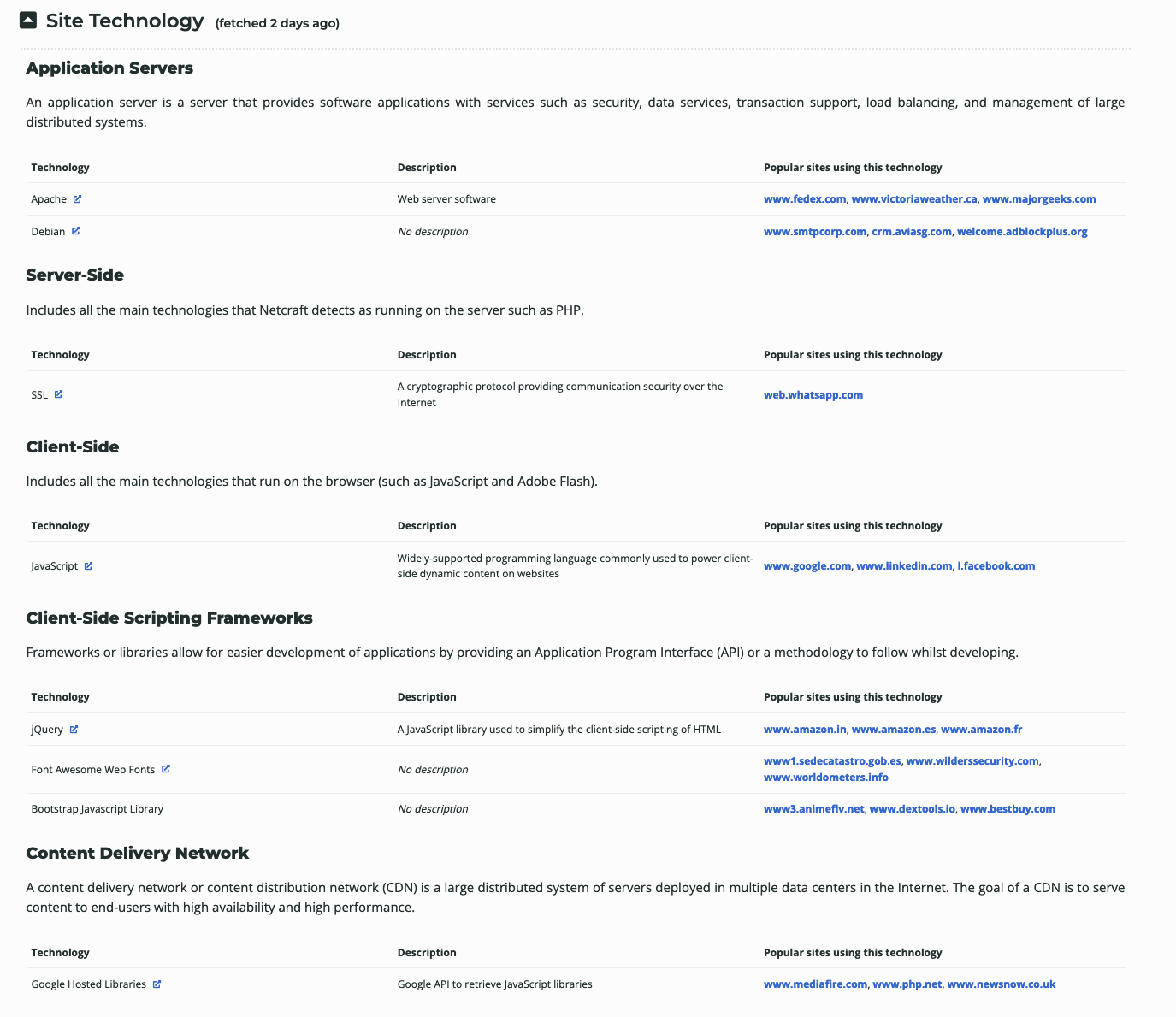

Figure 8: Site Technology for www.megacorpone.com

This list of subdomains and technologies will prove useful as we move on to active information gathering and exploitation. For now, we will add it to our notes.

Recently, Netcraft has decided to discontinue this part of their service. The info to answer these questions are in the images, or you can visit: https://www.wappalyzer.com/lookup/megacorpone.com/ to find the answers on a live site.

6.2.4. Open-Source Code

In the following sections, we'll explore various online tools and resources we can use to passively gather information. This includes open-source projects and online code repositories such as:

Code stored online can provide a glimpse into the programming languages and frameworks used by an organization. On a few rare occasions, developers have even accidentally committed sensitive data and credentials to public repos.

The search tools for some of these platforms will support the Google search operators that we discussed earlier in this Module.

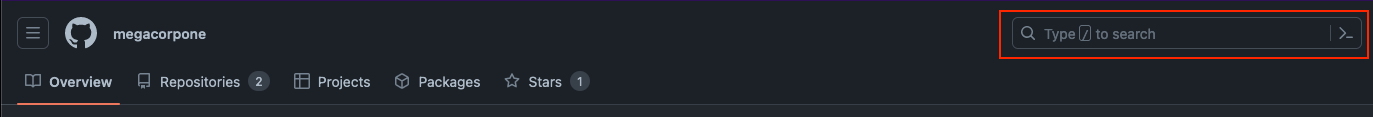

GitHub's search for example, is very flexible. We can use GitHub to search a user's or organization's repos; however, we need an account if we want to search across all public repos.

To perform any Github search, we first need to register a basic account, which is free for individuals and organizations.

Once we've logged in to our Github account, we can perform multiple keyword-based searches by typing into the top-right search field.

Figure 9: GitHub Search

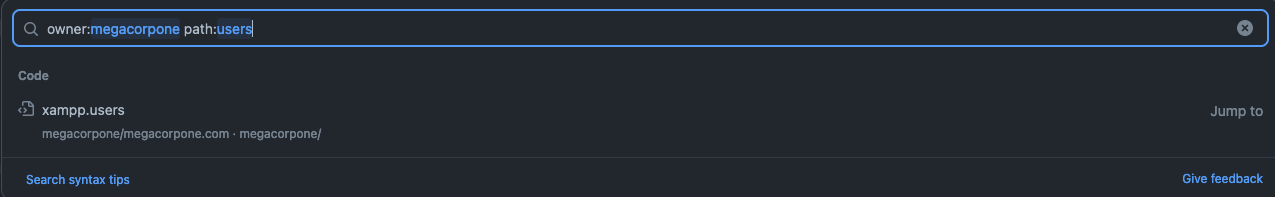

Let's search MegaCorp One's repos for interesting information. We can use path:users to search for any files with the word "users" in the filename and press ENTER.

Figure 10: File Operator in GitHub Search

Our search only found one file - xampp.users. This is nevertheless interesting because XAMPP is a web application development environment. Let's check the contents of the file.

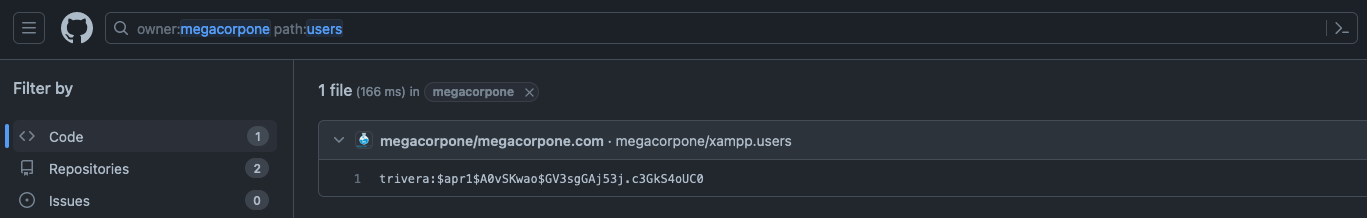

Figure 11: xampp.users File Content

This file appears to contain a username and password hash, which could be very useful when we begin our active attack phase. Let's add it to our notes.

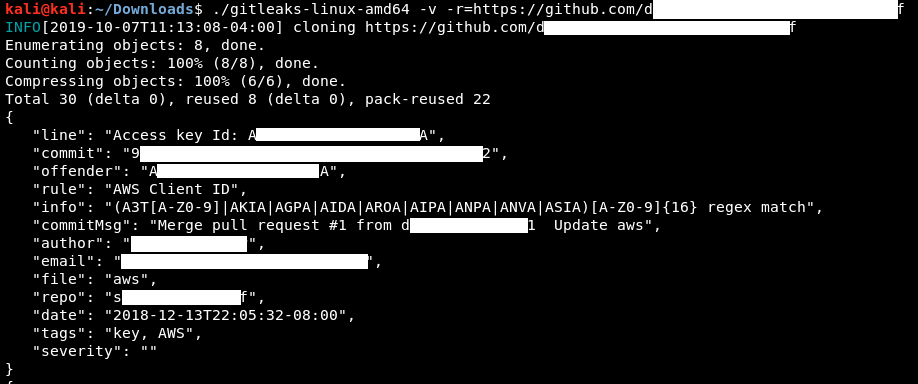

This manual approach will work best on small repos. For larger repos, we can use several tools to help automate some of the searching, such as Gitrob and Gitleaks.. Most of these tools require an access token to use the source code-hosting provider's API.

The following screenshot shows an example of Gitleaks finding an AWS access key ID in a file.

Figure 12: Example Gitleaks Output

Obtaining these credentials allows us unlimited access to the same AWS account and could lead to a compromise of any cloud service managed by this identity.

Warning

Tools that search through source code for secrets, like Gitrob or Gitleaks, generally rely on regular expressions or entropy-based detections to identify potentially useful information. Entropy-based detection attempts to find strings that are randomly generated. The idea is that a long string of random characters and numbers is probably a password. No matter how a tool searches for secrets, no tool is perfect and they will miss things that a manual inspection might find.

6.2.5. Shodan

As we gather information on our target, it is important to remember that traditional websites are just one part of the internet.

Shodan is a search engine that crawls devices connected to the internet, including the servers that run websites, but also devices like routers and IoT devices.

To put it another way, Google and other search engines search for web server content, while Shodan searches for internet-connected devices, interacts with them, and displays information about them.

Although Shodan is not required to complete any material in this Module or the labs, it's worth exploring a bit. Before using Shodan we must register a free account, which provides limited access.

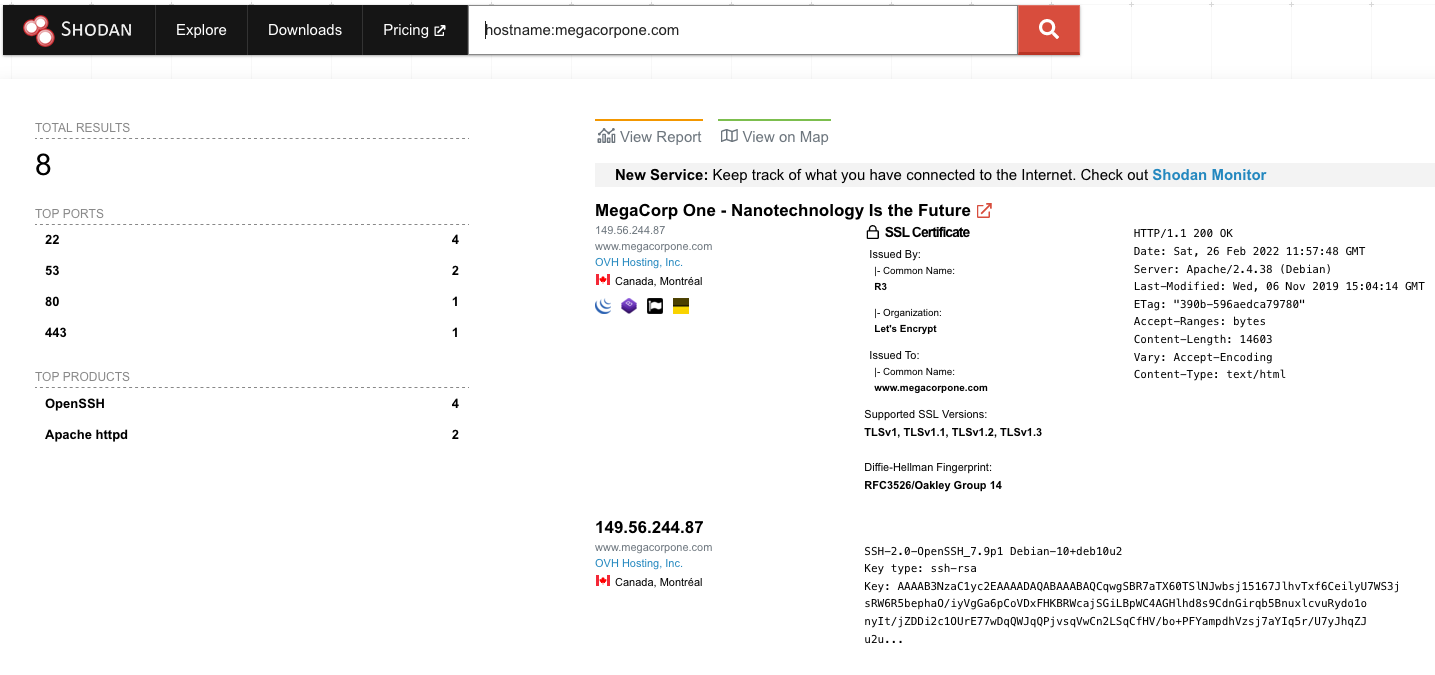

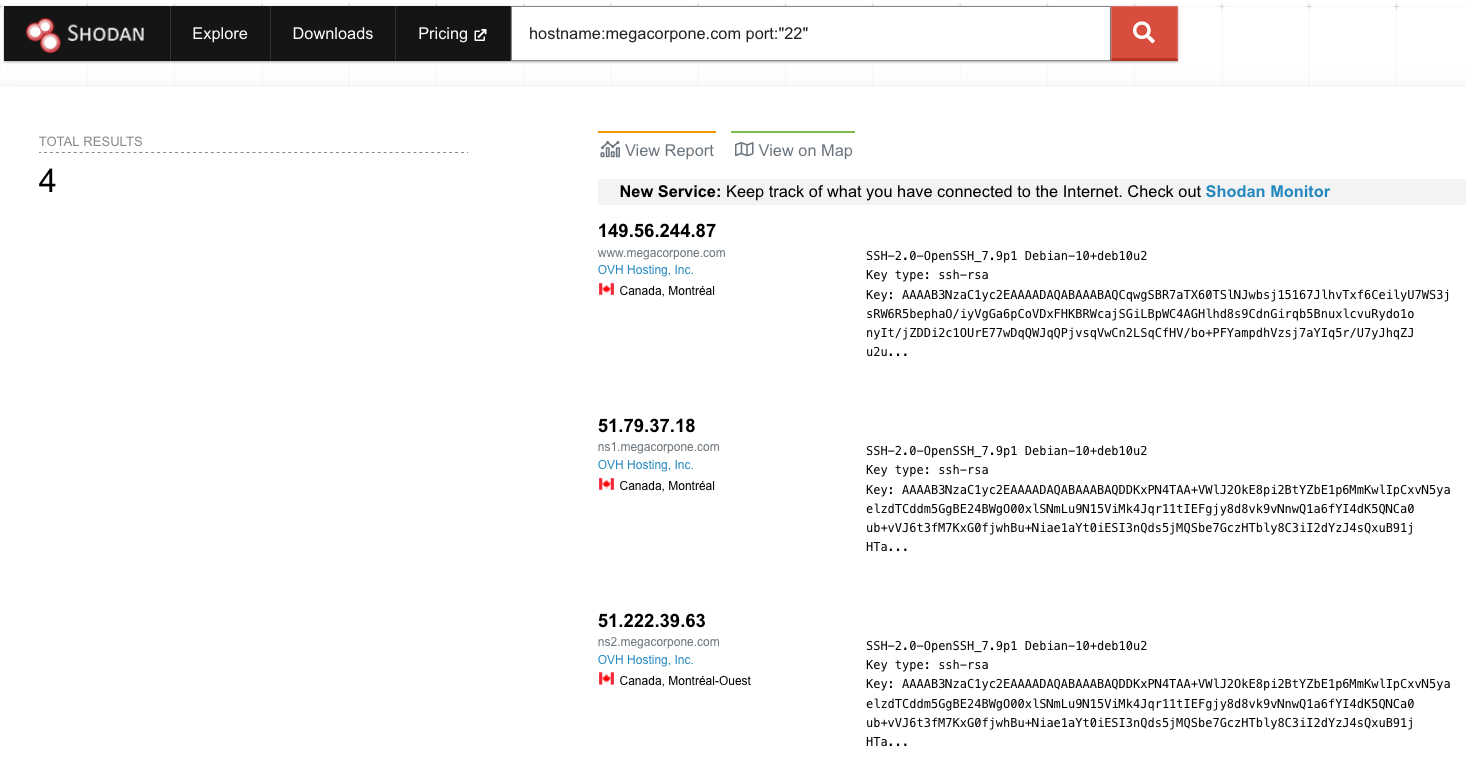

Let's start by using Shodan to search for hostname:megacorpone.com.

Figure 13: Searching MegaCorp One's domain with Shodan

In this case, Shodan lists the IPs, services, and banner information. All of this is gathered passively, avoiding interacting with the client's web site.

This information gives us a snapshot of our target's internet footprint. For example, there are four servers running SSH. We can drill down to refine our results by clicking on SSH under Top Ports on the left pane.

Figure 14: MegaCorp One servers running SSH

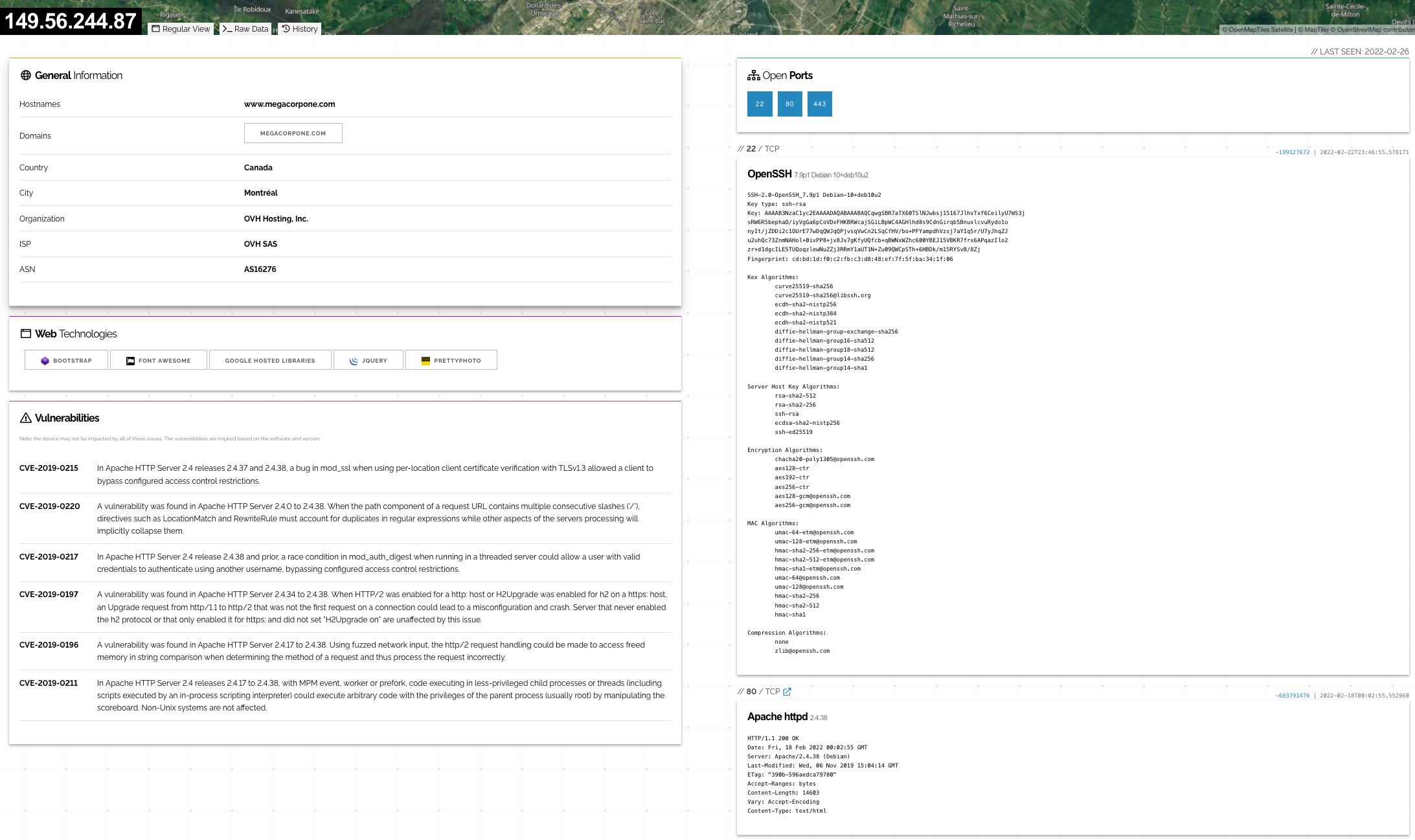

Based on Shodan's results, we know exactly which version of OpenSSH is running on each server. If we click on an IP address, we can retrieve a summary of the host.

Figure 15: Shodan Host Summary

We can review the ports, services, and technologies used by the server on this page. Shodan will also reveal if there are any published vulnerabilities for any of the identified services or technologies running on the same host. This information is invaluable when determining where to start when we move to active testing.

6.2.6. Security Headers and SSL/TLS

There are several other specialty websites that we can use to gather information about a website or domain's security posture. Some of these sites blur the line between passive and active information gathering, but the key point for our purposes is that a third-party is initiating any scans or checks.

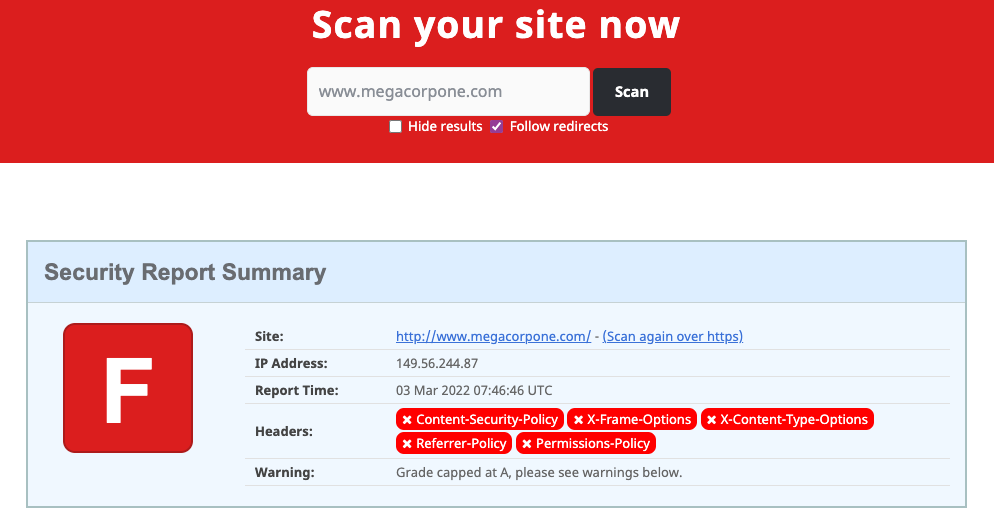

One such site, Security Headers, will analyze HTTP response headers and provide basic analysis of the target site's security posture. We can use this to get an idea of an organization's coding and security practices based on the results.

Let's scan www.megacorpone.com and check the results.

Figure 16: Scan results for www.megacorpone.com

The site is missing several defensive headers, such as Content-Security-Policy and X-Frame-Options. These missing headers are not necessarily vulnerabilities in and of themselves, but they could indicate web developers or server admins that are not familiar with server hardening.

Warning

Server hardening is the overall process of securing a server via configuration. This includes processes such as disabling unneeded services, removing unused services or user accounts, rotating default passwords, setting appropriate server headers, and so forth. We don't need to know all the ins and outs of configuring every type of server, but understanding the concepts and what to search for can help us determine how best to approach a potential target.

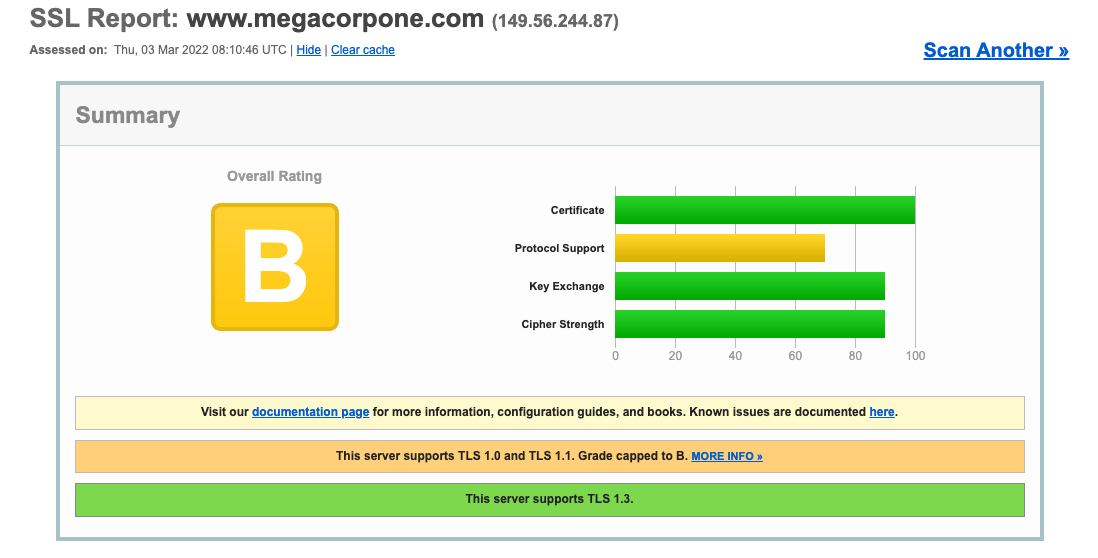

Another scanning tool we can use is the SSL Server Test from Qualys SSL Labs. This tool analyzes a server's SSL/TLS configuration and compares it against current best practices. It will also identify some SSL/TLS related vulnerabilities, such as Poodle or Heartbleed. Let's scan www.megacorpone.com and check the results.

Figure 17: SSL Server Test results for www.megacorpone.com

The results seem better than the Security Headers check. However, this shows that the server supports TLS versions such as 1.0 and 1.1, which are deemed legacy as they implement insecure [cipher suites](