3. Introduction To Cybersecurity

We will cover the following Learning Units in this Learning Module:

- The Practice of Cybersecurity

- Threats and Threat Actors

- The CIA Triad

- Security Principles, Controls, and Strategies

- Cybersecurity Laws, Regulations, Standards, and Frameworks

- Career Opportunities in Cybersecurity

This Module is designed to provide learners, regardless of current proficiency or experience, with a solid understanding of the fundamental principles of cybersecurity. It is intended for a wide range of individuals, from employees working adjacent to information technology or managing technical teams to learners just getting started in the highly dynamic information security field.

Completing this Module will help learners build a useful base of knowledge for progressing onto more technical, hands-on Modules.

An in-depth analysis of each concept is outside the scope of this Module. To learn more about the concepts introduced here, learners are encouraged to progress through the 100-level content in the OffSec Learning Library.

Throughout this Module, we'll examine some recent examples of cyber attacks and analyze their impact as well as potential prevention or mitigation steps. We'll also supply various links to articles, references, and resources for future exploration. Please review these links for additional context and clarity.

3.1. The Practice of Cybersecurity

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objectives:

- Recognize the challenges unique to information security

- Understand how "offensive" and "defensive" security reflect each other

- Begin to build a mental model of useful mindsets applicable to information security

3.1.1. Challenges in Cybersecurity

Cybersecurity has emerged as a unique discipline and is not a sub-field or niche area of software engineering or system administration. There are a few distinct characteristics of cybersecurity that distinguish it from other technical fields. First, security involves malicious and intelligent actors (i.e. opponents).

The problem of dealing with an intelligent opponent requires a different approach, discipline, and mindset compared to facing a naturally-occurring or accidental problem. Whether we are simulating an attack or defending against one, we will need to consider the perspective and potential actions of our opponent and try to anticipate what they might do. Because our opponents are human beings with agency, they can reason, predict, judge, analyze, conjecture, and deliberate. They can also feel emotions like happiness, sorrow, greed, fear, triumph, and guilt. Both attackers and defenders can leverage the emotions of their human opponents. For example, an attacker might rely on embarrassment by holding a computer system hostage and threaten to publish its data. Defenders, meanwhile, might leverage fear to dissuade attackers from entering their networks. This reality means human beings are a critical component of cybersecurity.

Another important aspect of security is that it usually involves reasoning under uncertainty. Although we have plenty of deductive skills, we are by no means mentally omniscient. We cannot determine everything that follows from a given truth, and we cannot know or remember an infinite number of facts.

Consider how a game like chess is different from a game like poker. In chess, you know everything that your opponent does about the game state (and vice versa). You may not know what they are thinking, but you can make predictions about their next move based on the same information that they are using to determine it. Playing poker, however, you do not have all of the information that your opponent possesses, so you must make predictions based on incomplete data.

When considering the mental perspectives of attackers and defenders, information security is a lot closer to poker than chess. For example, when we simulate an attack, we will never know everything there is to know about the machine/system/network/organization we are targeting. We therefore must make assumptions and estimate probabilities, sometimes implicitly and sometimes explicitly.

Conversely, as defenders, we will not be aware of every potential attack vector or vulnerability we might be exposed to. We therefore need to hedge our bets and make sure that our attack surfaces that are most likely to be vulnerable are adequately protected.

The problem of the intelligent adversary and the problem of uncertainty both suggest that understanding cybersecurity necessitates learning more about how we think as human agents, and how to solve problems. This means we'll need to adopt and nurture specific mindsets that will help us as we learn and apply our skills.

3.1.2. A Word on Mindsets

Security is not only about understanding technology and code but also about understanding your own mind and that of your adversary. We tend to think of a mindset as a set of beliefs that inform our personal perspective on something.

Two contrasting examples of well-known mindsets are the fixed mindset and the growth mindset.

An individual with a fixed mindset believes that their skill/talent/capacity to learn is what it is and that there is no gain to be made by trying to improve.

On the other hand, a growth mindset encourages the belief that mental ability is flexible and adaptable and that one can grow their capacity to learn over time.

Research suggests that, for example, a mindset in which we believe ourselves capable of recovering from a mistake makes us measurably better at doing so. This is just one aspect of the growth mindset, but it's an important one. This is because security requires us to make mistakes and learn from them and to be constantly learning and re-evaluating.

Another extremely valuable mindset is the aptly-coined security mindset. Proposed by security researcher Bruce Schneier. This mindset encourages a constant questioning of how one can attack (or defend) a system. If we can begin to ask this question automatically when encountering a novel idea, machine, system, network, or object, we can start noticing a wide array of recurring patterns.

At OffSec, we encourage learners to adopt the "Try Harder" mindset. To better understand this mindset, let's quickly consider two potential perspectives in a moment of "failure."

-

If my attack or defense fails, it represents a truth about my current skills/processes/configurations/approach as much as it is a truth about the system.

-

If my attack or defense fails, this allows me to learn something new, change my approach, and do something differently.

These two perspectives help provide someone with the mental fortitude to make mistakes and learn from them, which is essential in any cybersecurity sub-field. More information about how to learn and the Try Harder mindset can be found in the "Effective Learning Strategies" Module that is part of this introductory Learning Path.

3.1.3. On Emulating the Minds of our Opponents

It's worth pausing to consider the particular attention that we will give to the offensive side of security, even in many of our defensive courses and Modules. One might wonder why a cybersecurity professional whose primary interest and goal is defending a network, organization, or government should also learn the offensive side.

Let's take the analogy of a medieval monarch building a castle. If the monarch learns that their enemy has catapults capable of hurling large boulders, they might design their castle to have thicker walls. Similarly, if their enemy is equipped with ladders, the monarch might give their troops tools to push the ladders off the walls.

The more this monarch knows about their would-be attacker and the more they can think like an attacker, the better defense they can build. The monarch might engage in "offensive" types of activities or audits to understand the gaps in their own defenses. For example, they could conduct "war games" where they direct their own soldiers to mock-battle each other, helping them fully understand the capabilities and destructive potential of a real attacker.

In cybersecurity, enterprises might hire an individual or a firm to perform a penetration test, also known as a pentest. A penetration tester takes on the role of an attacker to better understand the system's vulnerabilities and exposed weaknesses.

Leveraging the skill-sets and mindsets of an attacker allows us to better answer questions like:

- "How might an attacker gain access?"

- "What can they do with that access?" -" What are the worst possible outcomes from an attack?"

While learning hacking skills is (of course) essential for aspiring penetration testers, we also believe that defenders, system administrators, and developers will greatly benefit from at least a cursory education in offensive techniques and technologies as well.

Conversely, it's been our experience that many of the best penetration testers and web application hackers are those who have had extensive exposure to defending networks, building web applications, or administrating systems.

3.2. Threats and Threat Actors

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objectives:

- Understand how attackers and defenders learn from each other

- Understand the differences between risks, threats, vulnerabilities, and exploits

- List and describe different classes of threat actors

- Recognize some recent cybersecurity attacks

- Learn how malicious attacks and threats can impact an organization and individuals

The term cybersecurity came to mainstream use from a military origin. For clarity, we'll use cybersecurity to describe the protection of access and information specifically on the Internet or other digital networks. While included within the broader context of cybersecurity, information security also examines the protection of physical information-storing assets, such as servers or physical vaults.

As we explore various threats and threat actors throughout this Module, we'll mainly consider their online capabilities. Therefore, we'll generally use the term cybersecurity here, but won't be too concerned about using information security as a synonym.

3.2.1. The Evolution of Attack and Defense

Cybersecurity can be especially fascinating because it involves multiple agents trying to achieve mutually exclusive outcomes. In the most basic example, a defender wants to control access to an asset they own, and an attacker wants to gain control over the same asset. This is interesting because both roles, defender and attacker, exist on the continued persistence of the other. In particular, each will become more skilled and sophisticated because of the efforts (or imagined efforts) of their counterpart.

The attacker-defender relationship dynamic helps to fundamentally explain why cybersecurity becomes exponentially more complicated over time. To understand this dynamic better, let's introduce the fictional characters Alice and Bob. We'll make use of them often throughout the OffSec Learning Library and the cryptography literature in various contexts to demonstrate examples and thought experiments.

For this particular story, let's imagine that Bob has an asset that he wants to defend: a great banana tree! Bob wants to make sure that only he can pick its bananas. Meanwhile, attacker Alice would love to nothing more than to steal Bob's bananas.

First, Bob doesn't pay any special attention to the security of his tree. It's relatively easy for Alice to just walk up to it and steal a banana. As Alice gets better and better at stealing however, Bob will also get better at protecting his tree.

When Bob first realizes Alice's treachery, he learns that standing guard prevents Alice from attempting to steal bananas. But Alice hypothesizes that Bob must sleep at some point. She pays attention to when Bob goes to sleep, then quietly sneaks up to the tree to steal.

Bob then figures out how to build a tall stone wall around the tree. Alice struggles to break through it or climb over it. Eventually, she learns how to dig under the wall.

Next, Bob trains a guard dog to protect the tree. Alice learns that she can pacify the dog with treats.

Bob takes a hardware security course and installs cameras and alarms to warn him anytime Alice is nearby. Alice learns how to disable the cameras and alarms.

This cycle can continue almost indefinitely. Strangely, both attacker and defender depend on each other to increase their skill sets and better understand their respective crafts.

We can take this analogy further to include compliance and risk management aspects of security. At some point, Bob accepts the risk that Alice may steal bananas and decides to get insurance. But his banana insurance won't pay for stolen bananas unless he complies with their requirements for risk mitigation, which entail having a sturdy wall and guard dog.

3.2.2. Risks, Threats, Vulnerabilities, and Exploits

Like many technical fields, cybersecurity relies on a significant amount of jargon, acronyms, and abbreviations. Throughout the OffSec Learning Library, we'll try to introduce terms and vocabulary as they come up organically. Before we learn about various cybersecurity theories and principles, however, it's important to define a few terms so we can follow what we're learning. Let's begin with a cursory review of some of the basic concepts that cybersecurity is about: risks, threats, vulnerabilities, and exploits.

The most fundamental of these four terms is risk because it applies to many domains outside of cybersecurity and information technology. A simple way to define risk is to consider two axes: the probability that a negative event will occur, and the impact on something we value if such an event happens. This definition allows us to conceptualize risks via four quadrants:

- Low-probability, low impact events

- Low-probability, high impact events

- High-probability, low impact events

- High-probability, high impact events

As cybersecurity professionals, we should always consider risk by examining the questions:

- How likely is it that a particular attack might happen?

- What would be the worst possible outcome if the attack occurs?

When we can attribute a specific risk to a particular cause, we're describing a threat. In cybersecurity, a threat is something that poses risk to an asset we care about protecting. Not all threats are human; if our network depends on the local electricity grid, a severe lightning storm could be a threat to ongoing system operations.

Nevertheless, in many cases, we are focused on human threats, including malicious programs built by people. A person or group of people embodying a threat is known as a threat actor, a term signifying agency, motivation, and intelligence. We'll learn more about different kinds of threat actors in the next section.

For a threat to become an actual risk, the target being threatened must be vulnerable in some manner. A vulnerability is a flaw that allows a threat to cause harm. Not all flaws are vulnerabilities. To take a non-security example, let's imagine a bridge. A bridge can have some aesthetic flaws; maybe some pavers are scratched or it isn't perfectly straight. However, these flaws aren't vulnerabilities because they don't pose any risk of damage to the bridge. Alternatively, if the bridge does have structural flaws in its construction, it may be vulnerable to specific threats such as overloading or too much wind.

Let's dive into an example. In December 2021, a vulnerability was discovered in the Apache Log4J library, a popular Java-based logging library. This vulnerability could lead to arbitrary code execution by taking advantage of a JNDI Java toolkit feature which, by default, allowed for download requests to enrich logging. If a valid Java file was downloaded, this program would be executed by the server. This means that if user-supplied input (such as a username or HTTP header) was improperly sanitized before being logged, it was possible to make the server download a malicious Java file that would allow a remote, unauthorized user to execute commands on the server.

Due to the popularity of the Log4j library, this vulnerability was given the highest possible rating under the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) used to score vulnerabilities: 10.0 Critical. This rating led to a frenzied aftermath including vendors, companies, and individuals scrambling to identify and patch vulnerable systems as well as search for indications of compromise. Additional Log4J vulnerabilities were discovered soon after, exacerbating matters.

This vulnerability could have been prevented by ensuring that user-supplied data is properly sanitized. The issue could have been mitigated by ensuring that potentially dangerous features (such as allowing web requests and code execution) were disabled by default.

In computer programs, vulnerabilities occur when someone who interacts with the program can achieve specific objectives that are unintended by the programmer. When these objectives provide the user with access or privileges that they aren't supposed to have, and when they are pursued deliberately and maliciously, the user's actions become an exploit.

The word exploit in cybersecurity can be used as both a noun and as a verb. As a noun, an exploit is a procedure for abusing a particular vulnerability. As a verb, to exploit a vulnerability is to perform the procedure that reliably abuses it.

Let's wrap up this section by exploring attack surfaces and vectors. An attack surface describes all the points of contact on our system or network that could be vulnerable to exploitation. An attack vector is a specific vulnerability and exploitation combination that can further a threat actor's objectives. Defenders attempt to reduce their attack surfaces as much as possible, while attackers try to probe a given attack surface to locate promising attack vectors.

3.2.3. Threat Actor Classifications

The previous section introduced threats and threat actors. Cybersecurity professionals are chiefly interested in threat actors since typically, most threats that our systems, networks, and enterprises are vulnerable to are human. Some key attributes of cybercrime compared to physical crime include its relative anonymity, the ability to execute attacks at a distance, and (typically) a lack of physical danger and monetary cost.

There are a wide variety of threat actors. Different people and groups have various levels of technical sophistication, different resources, personal motivations, and a variety of legal and moral systems guiding their behavior. While we cannot list out every kind of threat actor, there are several high-level classifications to keep in mind:

Individual Malicious Actors: On the most superficial level, anyone attempting to do something that they are not supposed to do fits into this category. In cybersecurity, malicious actors can explore digital tactics that are unintended by developers, such as authenticating to restricted services, stealing credentials, and defacing websites.

The case of Paige Thompson is an example of how an individual attacker can cause extreme amounts of damage and loss. In July 2019, Thompson was arrested for exploiting a router that had unnecessarily high privileges to download the private information of 100 million people from Capital One. This attack led to the loss of personal information including SSNs, account numbers, addresses, phone numbers, email addresses, etc.

This attack was partly enabled by a misconfigured Web Application Firewall (WAF) that had excessive permissions allowing it to list and read files. The attack could have been prevented by applying the principle of least privilege and verifying the correct configuration of the WAF. Since the attacker posted about their actions on social media, another mitigation could have included social media monitoring.

Malicious Groups: When individuals band together to form groups, they often become stronger than their individual group members. This can be even more true online because the ability to communicate instantly and at vast distances enables people to achieve goals that would have been impossible without such powerful communication tools. For example, the ability to quickly coordinate on who-does-what over instant messaging services is just as valuable to malicious cyber groups as it is to modern businesses. Malicious groups can have any number of goals but are usually more purposeful, organized, and resourceful than individuals. Thus, they are often considered to be one of the more dangerous threat actors.

Let's examine an example of a group-led attack. Over the span of several months, the "Lapsus$" group performed several attacks on a wide range of companies, stealing proprietary information and engaging in extortion. These attacks resulted in a loss of corporate data - including proprietary data such as source code, schematics, and other documentation. The attacks further resulted in the public exposure of data, and financial losses for companies that submitted to extortion.

The variety and sophistication of techniques used by the group show how this kind of malicious actor can be so dangerous. In particular, individuals within a group can bring their own specialties to the table that people working alone wouldn't be able to leverage. In addition, they can launch many different types of attacks at targets at a volume and velocity that an individual wouldn't be able to. There's a common truism in the cybersecurity industry that the attacker only needs to succeed once, while the defender must succeed every time. The efficacy of groups of attackers highlights this asymmetry.

There are only a few targeted mitigations available for such a wide variety of attack vectors. Because recruiting employees was one of the techniques used, awareness of internal threat actors and anomaly detection is key. Palo Alto Networks additionally suggests focusing on security best practices such as MFA, access control, and network segmentation.

Insider Threats: Perhaps one of the most dangerous types of threat actors, an insider threat is anyone who already has privileged access to a system and can abuse their privileges to attack it. Often, insider threats are individuals or groups of employees or ex-employees of an enterprise that become motivated to harm it in some capacity. Insider threats can be so treacherous because they are usually assumed to have a certain level of trust. That trust can be exploited to gain further access to resources, or these actors may simply have access to internal knowledge that isn't meant to be public.

During a PPE shortage in March 2020 at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Christopher Dobbins, who had just been fired as Vice President of a medical packaging company, used a fake account that he had created during his employment to access company systems and change/delete data that was critical to the company's distribution of medical supplies.

This attack resulted in the delayed delivery of critical medical supplies at a crucial stage of the pandemic and the disruption of the company's broader shipment operations. The danger of an insider threat is showcased here. The attack was enabled by a fake account created by a vice president, who may have had access to more permissions than what might be considered best practice for a VP of Finance.

This attack likely could have been prevented by applying the principle of least privilege, which we'll explore in a later section. Since the attack was enabled by a fake account, it also could have been prevented by rigorously auditing accounts. Lastly, since this activity was performed after the VP's termination, better monitoring of anomalous activity may have also prevented or mitigated the attack.

Nation States: Although international cyber politics, cyber war, and digital intelligence are vast subjects and significantly beyond the scope of this Module, we should recognize that some of the most proficient, resourceful, and well-financed operators of cyber attacks exist at the nation-state level within many different countries across the globe.

Since 2009, North Korean threat actors, usually grouped under the name Lazarus, have engaged in several different attacks ranging from data theft (Sony, 2014) to ransomware (WannaCry, 2017) to financial theft targeting banks (Bangladesh Bank, 2016) and cryptocurrencies - notably, the 2022 Axie Infinity attack. These attacks have resulted in the loss and leak of corporate data, including proprietary data (Sony) and financial losses for companies that paid a ransom.

An information assurance firm called NCC Group suggests the following steps prevent or mitigate attacks from the Lazarus group: network segmentation, patching and updating internet-facing resources, ensuring the correct implementation of MFA, monitoring for anomalous user behavior (example: multiple, concurrent sessions from different locations), ensuring sufficient logging, and log analysis.

3.2.4. Recent Cybersecurity Breaches

While the above section focused on who performs attacks, in this section we'll cover different kinds of breaches that have occurred in the last few years. We'll analyze some more recent cybersecurity attacks, discuss the impact they had on enterprises, users, and victims, and then consider how they could have been prevented or mitigated.

There are many examples of recent breaches to choose from. For each breach, we'll indicate the kind of attack that allowed the breach to occur. This list by no means represents a complete survey of all types of attacks, so instead we'll aim to provide a survey highlighting the scope and impact of cybersecurity breaches.

Social Engineering: Social Engineering represents a broad class of attacks where an attacker persuades or manipulates human victims to provide them with information or access that they shouldn't have.

In July 2020, attackers used a social engineering technique called spearphishing to gain access to(https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-53607374) an internal Twitter tool that allowed them to reset the passwords of several high-profile accounts. They used these accounts to tweet promotions of a Bitcoin scam. The impacts of this attack included financial losses for specific Twitter users, data exposure for several high-profile accounts, and reputational damage to Twitter itself.

To understand potential prevention and mitigation, we need to understand how and why the attack occurred. The attack began with phone spear-phishing and social engineering, which allowed attackers to obtain employee credentials and access to Twitter's internal network. This could have been prevented had employees been better equipped to recognize social engineering and spear-phishing attacks. Additional protections that could have prevented or mitigated this attack include limiting access to sensitive internal tools using the principle of least privilege and increased monitoring for anomalous user activity.

Phishing: Phishing is a more general class of attack relative to spear-phishing. While spear-phishing attacks are targeted to specific individuals, phishing is usually done in broad sweeps. Phishing strategy is usually performed by sending a malicious communication to as many people as possible, increasing the likelihood of a victim clicking a link or otherwise doing something that would compromise security.

In September 2021, a subsidiary of Toyota acknowledged that they had fallen prey to a Business Email Compromise (BEC) phishing scam. The scam resulted in a transfer of ¥ 4 billion (JPY), equivalent to roughly 37 million USD, to the scammer's account. This attack occurred because an employee was persuaded to change account information associated with a series of payments.

The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) recommends these and other steps be taken to prevent BEC:

- Verify the legitimacy of any request for payment, purchase, or changes to account information or payment policies in person.

- If this is not possible, verify legitimacy over the phone.

- Be wary of requests that indicate urgency.

- Carefully inspect email addresses and URLs in email communications.

- Do not open email attachments from people that you do not know.

- Carefully inspect the email address of the sender before responding.

Ransomware: Ransomware is a type of malware that infects computer systems and then locks a legitimate user from accessing it properly. Often, users are contacted by the attacker and asked for a ransom to unlock their machine or documents.

In May 2021, a ransomware incident occurred at Colonial Pipeline, a major American oil company. The attack lead to the disruption of fuel distribution for multiple days. This attack resulted in a loss of corporate data, the halting of fuel distribution, millions of dollars in ransomware payments, increased fuel prices, and fuel shortage fears.

In this attack, hackers gained access to Colonial Pipeline's network with a single compromised password. This attack could have been prevented or at least made less likely by ensuring that MFA was enabled on all internet-facing resources, as well as by prohibiting password reuse.

Credential Abuse: Credential Abuse can occur when an attacker acquires legitimate credentials, allowing them to log into machines or services that they otherwise would not be able to. Often, attackers can guess user passwords because they are predictable or weak.

In December 2020, a series of malicious updates were discovered in the SolarWinds Orion platform, an infrastructure monitoring and management tool. These malicious updates allowed malware to be installed on the environment of any SolarWinds customer that installed this update and led to the compromise of several these customers, including universities, US government agencies, and other major organizations.

As a supply-chain attack, this attack affected approximately 18,000 SolarWinds customers and led to the breach of a subset of customers including government agencies and other major companies. According to former SolarWinds CEO Kevin Thompson, this attack resulted from a weak password that was accidentally exposed publicly on GitHub. This attack could have been prevented by ensuring that passwords are sufficiently strong and by monitoring the internet for leaked secrets. CISA has also stated that this attack could have been mitigated by blocking outbound internet traffic from SolarWinds Orion servers.

Authentication Bypass: While Credential Abuse allows attackers to log in to services by legitimate means, Authentication Bypasses can allow attackers to ignore or step around intended authentication protocols.

Similar to the above SolarWinds attack, on July 2nd 2021 an attack was detected that took advantage of a vulnerability in software vendor Kaseya's VSA remote management tool. Attackers were able to bypass the authentication system of the remote tool to eventually push REvil ransomware from compromised customer Virtual System Administrator (VSA) servers to endpoints via a malicious update.

Since this attack targeted several Managed Service Providers (MSPs), its potential scope encompassed not only the MSP customers of Kaseya but also the customers of those MSPs. According to Brian Krebs, this vulnerability had been known about for at least three months before this ransomware incident. This attack could have been prevented by prioritizing and fixing known vulnerabilities in an urgent and timely manner.

3.3. The CIA Triad

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objectives:

- Understand why it's important to protect the confidentiality of information

- Learn why it's important to protect the integrity of information

- Explore why it's important to protect the availability of information

To understand offensive techniques, we need to understand the principles defenders should follow so that we can quickly identify opportunities to exploit their mistakes. Similarly, good defenders will benefit from understanding how attackers operate, including what kinds of biases and errors they are prone to.

One of the models often used to describe the relationship between security and its objects is known as the CIA triad. CIA stands for Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability. Each of these is a desirable property of the things we might want to secure, and each of these three properties can be attacked. Most (though not all) attacks against computer systems and networks will threaten one of these attributes. Let's begin with a high-level overview before we dive into each one:

- Confidentiality: Can actors who should not have access to the system or information access the system or information?

- Integrity: Can the data or the system be modified in some way that is not intended?

- Availability: Are the data or the system accessible when and how they are intended to be?

It is also important to note that in some cases, we may be far more concerned with one aspect of the CIA triad than others. For instance, if someone has a personal journal that contains their most secret thoughts, the confidentiality of the journal may be far more important to the owner than its integrity or availability. In other words, they may not be as concerned about whether someone can write to the journal (as opposed to reading it) or whether or not the journal is always accessible.

On the other hand, if we are securing a system that tracks medical prescriptions, the integrity of the data will be most critical. While it is important to prevent other people from reading what medications someone uses and it is important that the right people can access this list of medications. If someone were able to change the contents of the system, it could lead to potentially life-threatening consequences.

When we are securing a system and an issue is discovered, we will want to consider which of these three concepts, or which combination of them, the issue impacts. This helps us understand the problem in a more comprehensively manner and allows us to categorize the issues and respond accordingly.

3.3.1. Confidentiality

A system is Confidential if the only people who can access it are the people explicitly permitted to do so. A person's social media account credentials are considered confidential as long as the user's password is known only to the owner. If a hacker steals or guesses the password and can access the account, this would constitute an attack against confidentiality. Common attacks against confidentiality include network eavesdropping and credential stuffing.

Let's consider an example of an attack against confidentiality, assess its impact, and understand how it could have been prevented or mitigated. In August 2021, T-Mobile announced that hackers had accessed data associated with over 50 million current, former, and prospective customers. While no payment information, passwords, or PINs were accessed, some of the data included first and last names, dates of birth, social security numbers, and ID/drivers' license information. This data was subsequently offered for sale on the dark web.

The attack impacted the confidentiality of the personal information of millions of current, former, and prospective customers. The confidentiality of this information was subsequently further compromised by being made available for purchase on the dark web. This also led to further reputational damage to T-Mobile as the attack was one of several then-recent breaches.

There is limited information available on the exact methodology used by the attackers; however, they claim to have first compromised a router to gain access to over 100 servers including the database or databases that contained the affected customer data. This breach could have been prevented by ensuring that all internet-facing resources were properly configured, patched, and updated. Then the network should have been monitoring for anomalous user behavior, and by instituting better network segmentation.

Private documents such as driver's licenses ought to be confidential because they contain information that can identify individuals.

However, not all information possessed by a company is necessarily confidential. For example, T-Mobile's board members are publicly listed on their website. Therefore, if an attack were to divulge that information, it would not be a breach of confidentiality.

3.3.2. Integrity

A system has Integrity if the information and functionality it stores is only that which the owner intends to store. Integrity is concerned with maintaining the accuracy and reliability of data and services. Merely logging on to a user's social media account by guessing their password is not an attack against integrity. However, if the attacker starts to post messages or delete information, this would become an attack on integrity as well. A common attack against integrity is arbitrary code execution.

In January 2022, researchers identified a new wiper malware, dubbed WhisperGate, being used against Ukrainian targets. This malware has two stages: stage one overwrites the Master Boot Record (MBR) to display a fake ransomware note, while stage two downloads further malware overwriting files with specific extensions, thus rendering them corrupt and unrecoverable. This attack impacts the integrity of data on the affected system by overwriting files in an irrecoverable manner, effectively deleting them.

In their advisory, Microsoft recommended that potential targets take the following steps to protect themselves: enable MFA to mitigate potentially compromised credentials, enable Controlled Folder Access (CFA) in Microsoft Defender to prevent MBR/VBR tampering, use provided IoCs to search for potential breaches, review and validate authentication activity for all remote access, and investigate other anomalous activity. More information about the technical details of the attack has been published by CrowdStrike.

Put simply, integrity is important for an enterprise to protect because other businesses and consumers need to be able to trust the information held by the enterprise.

3.3.3. Availability

A system is considered Available if the people who are supposed to access it can do so. Imagine an attacker has gained access to a social media account and also posted content of their choosing. So far, this would constitute an attack against confidentiality and integrity. If the attacker changes the user's password and prevents them from logging on, this would also become an attack against availability. A common attack against availability is a denial of service attack.

On February 24, 2022, at the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Viasat's satellite broadband service was hit by a Denial of Service (DoS) attack that brought down satellite internet for Ukrainian customers, including the Ukrainian government and military. This attack utilized a then-novel wiper malware known as AcidRain.

The impact of this attack was that Viasat's satellite internet was temporarily unavailable in Ukraine at a critical moment at the beginning of the invasion, disrupting communication and coordination. Very little information is available about how this attack unfolded. Viasat stated that a VPN "misconfiguration" allowed initial access. Though it is unclear what the specific misconfiguration was, this attack could have been prevented by ensuring proper VPN configuration.

It is possible that this attack could have been prevented, though we should acknowledge the well-known difficulties associated with prevention, by following general guidance for defending against Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs). This guidance suggests ensuring complete visibility into one's environment, engaging in threat intelligence, and performing threat hunting, among other recommendations.

3.3.4. Balancing the Triad with Organizational Objectives

Before concluding this section, let's zoom out and consider how prioritizing the CIA triad can impact an organization. In particular, an important nuance to consider is that security controls themselves can sometimes be a detriment to availability. Extremely strong security isn't always optimal for an organization. If security is so strong that users are not able to use the systems, or frequently become frustrated with the systems, this may lead to inefficiency, low morale, and potentially the collapse of the organization.

Balancing security controls with availability is a critical and continuous process of evaluation, exploration, threat modeling, discussion, testing, and releasing. Making rules that prevent employees from participating in improvements is an easy way to ruin a security program.

Security is everyone's responsibility, and processes that receive feedback from the entire organization as well as educate employees about how to use the controls are typically important to a successful security program.

3.4. Security Principles, Controls, and Strategies

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objectives:

- Understand the importance of multiple layers of defense in a security strategy

- Describe threat intelligence and its applications in an organization

- Learn why access and user privileges should be restricted as much as possible

- Understand why security should not depend on secrecy

- Identify policies that can mitigate threats to an organization

- Understand different security models

- Determine which controls an organization can use to mitigate cybersecurity threats

3.4.1. Security Principles

During this Learning Unit, we'll begin to explore a few we might encounter throughout our OffSec Learning Journey.

Two excellent resources for security principles are David Wheeler's website and the OWASP cheatsheet.

Although this subject could be its own in-depth Module, for now, we'll cover a few high-level descriptions.

The Principle of Least Privilege expresses the idea that each part within a system should only be granted the lowest possible privileges needed to achieve its task. Whether referring to users on a machine or lines of code in a program, correctly adhering to this discipline can greatly narrow the attack surface.

Earlier we referenced the 2019 Capital One attack. We'll recall that this attack was facilitated by leveraging a Web Application Firewall with permissions that were too high for its required functions. It's important to understand that the Principle of Least Privilege does not only apply to human individuals or groups, but any entity (including machines, routers, and firewalls) that can read, write, or modify data.

The Zero Trust security model takes the Principle of Least Privilege and carries it to its ultimate conclusion. This model advocates for removing all implicit trust in networks and has a goal of protecting access to resources, often with granular authorization processes for every resource request. Zero Trust encapsulates five key elements: Just in Time Access (JITA), which requires access to be validated just before access is granted; Just Enough Access (JEA), which aligns with the traditional concept of least privilege; tokenization and encryption to protect data; dynamic (or adaptive) access control policies to ensure that policy is always fit for purpose; and microsegmentation, to limit access to the appropriate level of granularity.

Open Security, a somewhat counter-intuitive principle, states that the security of a system should not depend on its secrecy. In other words, even if an attacker knows exactly how the system's security is implemented, the attacker should still be thwarted. This isn't to say that nothing should be secret. Credentials are a clear case where the security of a password depends on its secrecy. However, we'd want our system to be secure even if the attacker knows there is a password, and even if they know the cryptographic algorithm behind it.

Defense in Depth advocates for adding defenses to as many layers of a system as possible, so that if one is bypassed, another may still prevent full infiltration. An example of defense in depth outside the context of cybersecurity would be a garage that requires entering an electronic code, using a key on a bolted door lock, and then finally disabling a voice-activated internal alarm system to open the garage.

Many organizations do not apply adequate defenses for their systems. They lean too heavily on external tools or providers that focus on one specific area of defense. This can lead to single points of failure, resulting in a very weak security posture. We must learn to apply many layers of controls, and design our systems with defense in depth to resist more threats and better respond to incidents.

3.4.2. Security Controls and Strategies

To meet the ideals of concepts such as least privilege, open security, and defense-in-depth, we need to implement Security Strategies. These can include interventions like:

- 24/7 vigilance

- Threat modeling

- Table top discussions

- Continuous training on tactics, processes, and procedures

- Continuous automated patching

- Continuous supply chain verification

- Secure coding and design

- Daily log reviews

- Multiple layers of well-implemented Security Controls

This might feel overwhelming at first. In particular, a defense-in-depth strategy involves people and technologies creating layers of barriers to protect resources.

In the CIA Triad Learning Unit, we mentioned that a consequence of strong security can be reduced availability. If a system's security is prioritized over availability, then there may be increased downtime and ultimately increased user frustration. An example of this could be using the Kerberos authentication protocol without a fallback authentication method. In GNU/Linux, Kerberos might be configured without a failsafe, with no alternate network access authorization method. This can result in no one being able to access network services if there is a Kerberos issue. If security is the top priority, this could be ideal depending on the organization's goals. However, if availability is the top priority, such an approach could damage the system by improving its security without care.

Security controls can also be extremely time-consuming to properly use and maintain. If a control is expensive enough, an organization could lose profitability. Security controls must also be balanced with financial resources and personnel restraints.

Next, let's explore a variety of different security controls that an organization might implement.

3.4.3. Security Models

A security model is a type of schema that is used to implement security controls in information systems. They rarely specify specific controls but they present a theoretical framework and, in some cases, a set of rules that can be implemented in several different contexts.

Many of the most well-known models target access controls. We'll focus on examples of these in this section. Some of these specifically focus on confidentiality or integrity, others are more general.

First, let's consider a security model that deals primarily with confidentiality. The Bell–LaPadula model is used to enforce access controls in systems with multiple security levels (for instance, unclassified, confidential, secret and top secret). It's often used in a government or military context to determine who can access what objects at the various security levels. In this model, individuals cannot read content with a security level higher than their own (known as the Simple Security Property) or write content with a security level lower than their own (known as the Star Security Property). In certain contexts, they may not be allowed to read or write at a level other than their own (known as the Discretionary Security Property).

Similarly, the Brewer and Nash model is used to enforce access controls to maintain confidentiality, but with the specific aim of minimizing conflict of interest. This may be used by accounting or consulting organizations. The model uses data segregation and dynamic access controls. Dynamic access controls may function by denying access to certain individuals based on other information that they have viewed or have access to. For instance, an organization that works with customers who compete with one another may temporarily restrict an individual from accessing a company's data once they have accessed data belonging to their competitor.

Next, let's consider some security models that deal primarily with integrity. The Biba model is also used to enforce access controls and is designed to protect the integrity of information where individuals and information are assigned different integrity levels. In this model, individuals cannot read data with a lower integrity level than their own (known as the Simple Integrity Property) or write content with an integrity level higher than their own (known as the Star Integrity Property). Another rule, states that individuals cannot request access to information with a higher integrity level than their own (known as the Invocation Property).

The Clark-Wilson model is another module used to protect data integrity. This is implemented through access control triples (or simply triples), which consist of a subject, program (also known as a transaction) and object. According to this model, individual subjects don't have direct access to data objects but only access and modify them through a series of programs, which themselves operate on data objects and enforce integrity policies.

Other access control security modules are focused on access controls more generally. One example of this is Role-Based Access Control (RBAC). This security model, widely used in cloud computing Identity and Access Management (IAM), grants permissions to roles, which are in turn applied to individual users. Rather than permissions being granted to each user directly, permissions are granted to users based on the roles that they have.

Another variant is Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC). This security model is based on a series of attributes that are applied to users and objects, and rules use these attributes to determine which users can perform which types of access on which objects. ABAC has the advantage of providing more granular access control and of being more dynamic.

These are only a few security models but they give us a general idea of what security models are, what goals specific models have, where they may be used and what level of specification they involve.

3.4.4. Shift-Left Security

One of the best ways to avoid extra costs and impacts on availability is to design an entire system so that security is built into the service architecture, rather than requiring many additional software layers. To design systems with built-in security, the idea of shift-left security can improve efficiency. The idea of shift-left security is to consider security engineering from the outset when designing a product or system, rather than attempt to bake it in after the product has been built.

Without shift-left security, we might have developers shipping products without security, and then need to add additional layers of security on top of, or along with, the product. If the security team is involved in the development process, we have a better chance of creating a product with controls built in, making a more seamless user experience as well as reducing the need for additional security services.

Most applications do not have security built in and instead rely on platform-level security controls surrounding the services. This can work well; however, it can result in security being weaker or easier to bypass. For example, if a specific technology (for example, Kubernetes modules) is providing all of the security services, then someone who controls that technology (in this case, a Kubernetes administrator) could remove or tamper with it and bypass security for all services.

However, we once again need to consider business impact. In particular, shifting left can potentially cause slower production times because developers will need to explicitly think about security in addition to the product specifications. An organization therefore will need to decide what trade-offs they can make in their particular circumstance. Despite the potential reduction in security posture, focusing on platform-level security controls can provide the lowest friction to development efforts and the fastest time to market for application developers while producing a reasonable security posture.

3.4.5. Administrative Segmentation

It may seem okay to have an administrator bypass security controls based on their role and functional needs. Shouldn't we trust our administrators? However, when a threat is internal or otherwise able to obtain valid administrative credentials, our security posture becomes weaker. To defeat internal threats and threats that have acquired valid credentials or authentication capability, we must segment controls so that no single authority can bypass all controls. To accomplish this, we may need to split controls between application teams and administrators, or split access for administration between multiple administrators, as with Shamir's Secret Sharing (SSS).

With SSS, we might design a system so that three different administrator authorizations are required to authorize any one administrative root access. Shamir's secret sharing scheme enables a system to split access authorization requirements between multiple systems or persons. With this in place, we can design a system so that no one person has the root credentials.

3.4.6. Threat Modelling and Threat Intelligence

Before researching potential threats against an organization, it is vital for an organization to have a detailed inventory of their assets. It would make no sense to devote time and energy on identifying potential threats against Cisco devices when an organization only uses Juniper devices. After we've completed an inventory for both systems and software and we understand our organization's requirements, we're ready to begin researching potential threats. Security teams research (or leverage vendor research about) threats to different industries and software.

We can use this information in our Threat Modeling. Threat modeling involves taking data from real-world adversaries and evaluating those attack patterns and techniques against our people, processes, systems, and software. It is important to consider how the compromise of one system in our network might impact others.

Threat Intelligence is data that has been refined in the context of the organization: actionable information that an organization has gathered via threat modeling about a valid threat to that organization's success. Information isn't considered threat intelligence unless it results in an action item for the organization. The existence of an exploit is not threat intelligence; however, it is potentially useful information that might lead to threat intelligence.

An example of threat intelligence occurs when a relevant adversary's attack patterns are learned, and those attack patterns could defeat the current controls in the organization, and when that adversary is a potential threat to the organization. The difference between security information and threat intelligence is often that security information has only been studied out of context for the specific organization. When real threat intelligence is gathered, an organization can take informed action to improve its processes, procedures, tactics, and controls.

3.4.7. Table-Top Tactics

After concerning threat intelligence or other important information is received, enterprises may benefit from immediately scheduling a cross-organization discussion. One type of discussion is known as a table-top, which brings together engineers, stakeholders, and security professionals to discuss how the organization might react to various types of disasters and attacks. Conducting these regular table-tops discussions to evaluate different systems and environments is a great way to ensure that all teams know the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) for handling various scenarios. Often organizations don't build out proper TTPs, resulting in longer incident response times.

Table-top discussions help organizations raise cross-team awareness. This helps teams understand weaknesses and gaps in controls so they can better plan for different scenarios in their tactics, procedures, and systems designs. Having engineers and specialists involved in table-tops might help other teams find solutions to security issues, or vice-versa.

Let's imagine a scenario in which we learn that a phishing email attack on an administrator would represent a complete company compromise. To build up our defensive controls, we may decide to create an email access portal for administrators that is physically isolated. When the administrators view their email, they would do so through a screen displaying a client view into a heavily-secured email sandbox. This way, emails are opened up inside a sandboxed machine on separate hardware, instead of on administrative workstations that have production access.

Table-top security sessions are part of Business Continuity Planning (BCP). BCP also includes many other aspects such as live drill responses to situations like ransomware and supply-chain compromise. BCP extends outside of cybersecurity emergencies to include processes and procedures for natural disasters and gun violence. Routine table-top sessions and continuous gathering of relevant intelligence provide a proactive effort for mitigating future issues as well as rehearsing tactics, processes, and procedures.

3.4.8. Continuous Patching and Supply Chain Validation

Another defensive technique known as continuous automated patching is accomplished by pulling the upstream source code and applying it to the lowest development environment. Next, the change is tested and only moved to production if it is successful. We can leverage cloud provider infrastructure to spin up complete replicas of environments for testing these changes. Rather than continuously running a full patch test environment, we can create one with relative ease using our cloud provider, run the relevant tests, and then delete it. The primary risk of this approach is supply chain compromise.

Continuous supply chain validation happens by both the vendor and the consumer. It occurs when people and systems validate that the software and hardware received from vendors is the expected material and that it hasn't been tampered with. For the vendor, it ensures that the software and materials being sent out are verifiable by customers and business partners.

Continuous supply chain validation is difficult and sometimes requires more than software checks, such as physical inspections of equipment ordered. On the software side of supply chain security, we can use deeper testing and inspection techniques to evaluate upstream data more closely. We might opt to increase the security testing duration to attempt to detect sleeper malware implanted in upstream sources. Sleeper malware is software that is inactive while on a system for for some period of time, potentially weeks before it starts taking action.

Utilizing a software bill of materials (SBOM) as a way to track dependencies automatically in the application build process greatly helps us evaluate supply chain tampering. If we identify the software dependencies, create an SBOM with them, and package the container and SBOM together in a cryptographically-verifiable way, then we can verify the container's SBOM signature before loading it into production. This kind of process presents additional challenges for adversaries.

3.4.9. Backups

A backup is a copy of data made at a certain point in time. Backups enable us to restore data if it has been deleted or corrupted. Data can be deleted or corrupted in several different ways, for instance, as a result of an attack (ransomware, wiper malware, etc), human error or natural disasters (electrical surges, fire, etc), among other possibilities.

Since a backup is a copy of data at a specific point in time, restoring data using a backup only returns data to the state that it was in when the backup was taken. If that data does not change over time, this effectively allows us to ensure its availability and integrity. If it does change over time, restoration allows us to mitigate data loss.

In the second case, taking regular backups is an important part of data management because it reduces the difference between the backup and the state of the data when the incident occurs, further reducing data loss.

There are a few different types of backups: full, incremental and differential. A full backup is a complete copy of the data. This is the simplest solution and is easy to recover from since we simply restore the entire backup. The disadvantage is that it may be slow to copy large amounts of data. Further, it may be expensive to store many different copies, which we may wish to do if we want to retain different versions of the data.

An incremental backup copies files that have changed since the last backup, which may be either a full backup or another incremental backup. This reduces the amount of data that is backed up, the time needed to copy data, and the space needed to store it. However, this makes recovery slightly more complicated because the most recent version of the data must be reconstructed from multiple different backups.

A differential backup copies files that have changed since the last full backup. This is similar to an incremental backup except that it does not take prior incremental backups into account when determining which files have changed. For this reason, the time and storage space required for a differential backup is less than a full backup but more than an incremental backup. Recovering from differential backups, on the other hand is more complex than recovery from full backups but less complex than recovering from incremental backups.

The following table summarizes these backup types.

| Type | Backs up | Backup | Recovery | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full | all files | slowest | simple | most expensive |

| Differential | file changed since last full backup | faster | more complex | less expensive |

| Incremental | files changed since last full or incremental backup | fastest | most complex | least expensive |

Table 1 - Comparison of backup types

Warning

It's always a good idea to test our backup and restore processes before an incident on a scheduled basis as part of disaster recovery routine to make sure they work as expected.

The are two other types of backups that refer to the state of the system when the backup is made: hot and cold. A hot backup is taken from a running, online system. We can create these backups without shutting down the system or service. The backup can be stored on the same computer as the original files or on a different designated computer. Hot backups can be performed periodically, scheduled, or triggered by changes or specific conditions. Either way, this creates a backup of the current state of the system or files.

Cold backups, on the other hand, are taken when the system or service is offline. Cold backups are safer in terms of data consistency but require system downtime, which can be a significant drawback for systems that require full-time availability.

Backups can be stored in a few different places. For example, they can be stored on the source machine, on another machine, or on some sort of external medium such as an external hard drive, DVD, USB flash drive, magnetic tape, or other storage device.

Once we create a backup, we can detach the backup media and store it offline. This incurs obvious logistical challenges as well as a significant time and cost investment as we must buy external media and physically manage the media. However, this protects the backups from online threats, although they are still at risk from physical threats. If an adversary manages to steal the physical backup, they can obviously leverage that as part of an extortion scheme. To combat this, we can use escrow backup services in which we transport physical backups to a third party, which locks the backup in a secure location. This provides redundancy, separation and further assurance that we'll be able to protect and recover that data.

In contrast with offline backup storage, online storage solutions offer convenience, allowing us to store data on dedicated servers and restore quickly in the event of data loss. However, online backups are susceptible to deletion or alteration by adversaries.

We can offset this by creating read-only, protected backups which resist deletion and modification. To create protected hot backups, we need to remove our own access to certain functions, add security layers such as MFA or add multi-user authentication. Even with these measures in place, we're still at risk from unforeseen exploits or social engineering tactics that an adversary could use to delete the backups before activating the ransomware.

Warning

Although it can be difficult to engineer our own protected hot backup solution, there are various third-party solutions including those offered by Veeam, which offers comprehensive backup and replication features and Acronis, known for its cloud backup and cybersecurity protection services.

A hybrid approach using redundant backups is the safest approach. We can combine hot and cold backup strategies, as well as online and offline storage solutions. We should consider a strategy that makes the most sense given our business needs and level of accepted risk.

Specifically, we should focus on redundancy. We should adopt several different backup techniques so that if one backup system fails, we have another at our disposal. This creates defense in depth, a strategy that layers multiple security controls and measures to protect against a variety of different threats. The idea is that no single security measure is foolproof, so multiple layers of defense can help mitigate the risks of an attack.

Backups must also be stored securely. One of the ways that we can do this is by encrypting them. We'll discuss encryption in the next section.

3.4.10. Encryption

Beyond tracking software, many organizations likely want to leverage encryption. Encryption often protects us from adversaries more than any other type of control. While using encryption doesn't solve all problems, well-integrated encryption at multiple layers of controls creates a stronger security posture.

Keeping this in mind, there are some caveats to consider when it comes to encryption. Encrypting all our data won't be useful if we can't decrypt it and restore it when required. We must also consider some types of data that we won't want to decrypt as the information is to be used only ephemerally. One example of ephemeral encryption is TLS. Here, only the server and the client of that specific interaction can decrypt the information (not even the administrators). On top of this, the decryption keys only exist in memory for a brief time before being discarded.

Decryption keys in such a scenario are never on disk and never sent across the network. This type of privacy is commonly used when sending secrets or Personal Identifiable Information (PII) across the wire. Any required tracing and auditing data can be output from the applications rather than intercepted, and the secrets and PII can be excluded, encrypted, or scrubbed. PII can include names, addresses, phone numbers, email addresses, SSNs, and other information that can be used to track down or spy on a person.

Along with ensuring we can encrypt data, we should ensure that only the minimum required persons or systems can decrypt said data. We also probably want backups that are encrypted with different keys. In general, we don't want to reuse encryption keys for different uses, as each key should only have one purpose. A file encryption key might encrypt millions of files, but that key should be used for only that purpose, and not, for example, signing or TLS.

Although using encryption and backups are great practices, we also should implement protocols for routinely restoring from backups to ensure that we know how and that the process works for every component. In some cases, we don't need to back up detailed log data; however, most compliance and auditing standards require historic logs. Some specifications may even require that systems are in place to query for and delete specific historic log records.

3.4.11. Logging and Chaos Testing

Being able to access granular data quickly is of great benefit to an organization. Well-engineered logging is one of the most important security aspects of application design. With consistent, easy-to-process, and sufficiently-detailed logging, an operations team can more quickly respond to problems, meaning incidents can be detected and resolved faster.

Logging is not limited to just what happens on the network. Network equipment such as routers, switches and firewalls, the backbone of a company's network also need to be logged. This type of logging can include purchase date, OS version, and end of life date. Having this inventory allows management to not only budget for large purchases when the end of life date appears, but it also allow the security team to have a quick reference of their network devices.

Imagine a network administrator waking up the morning of the SolarWinds' attack. Would it be easier for the administrator to check an inventory database to verify if the company used SolarWinds devices, or having to call remote sites and have someone check server rooms.

Having an asset register also allows companies to track devices such as laptops or mobile devices. This helps in the event a device is lost, stolen, or when the device has reached its end-of-life.

As devices age, they fall out of warranty and need to be replaced. Having an asset inventory allows a company to be prepared for large equipment purchases.

The last control we'll explore is Chaos Testing. Chaos testing is a type of BCP or disaster recovery (DR) practice that is often handled via automation. For example, we might leverage a virtual machine that has valid administrative credentials in the production network to cause intentional disasters from within.

Chaos engineering includes a variety of different approaches, such as having red teams create chaos in the organization to test how well the organization can handle it, scheduling programmed machine shutdowns at various intervals, or having authenticated malicious platform API commands sent in. The goal is to truly test controls during messy and unpredictable situations. If a production system and organization can handle chaos with relative grace, then it is an indication that it will be robust and resilient to security threats.

3.5. Cybersecurity Laws, Regulations, Standards, and Frameworks

This Learning Unit covers the following Learning Objectives:

- Gain a broad understanding of various legal and regulatory issues surrounding cybersecurity

- Understand different frameworks and standards that help organizations orient their cybersecurity activities

- Be familiar with the anatomy of cyber perspective

3.5.1. Laws and Regulations

Much can be written about cybersecurity laws and regulations, especially since different countries and jurisdictions all have their own. Most of the items we'll discuss here are centered in the United States; however, some are applicable globally as well. As a security professional, it's always important to understand exactly which laws and regulations one might be subject to.

HIPAA: The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) is a United States federal law regulating health care coverage and the privacy of patient health information. Included in this law was a requirement to create of a set of standards for protecting patient health information, known as Protected Health Information (PHI). The standards that regulate how PHI can be used and disclosed are established by the Privacy Rule. This rule sets limits on what information can be shared without a patient's consent and grants patients several additional rights over their information, such as the right to obtain a copy of their health records.

Another rule known as the Security Rule outlines how electronic PHI (e-PHI) must be protected. It describes three classes of safeguards that must be in place:

- administrative (having a designated security official

- a security management process, periodic assessments, etc.)

- physical (facility access control, device security), and technical (access control, transmission security, audit abilities, etc.).

These rules also include provisions for enforcement and monetary penalties for non-compliance. Importantly, HIPAA also requires that covered entities (healthcare providers, health plans, business associates, etc.) provide notification if a PHI breach occurs.

FERPA: The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA) is a United States federal law regulating the privacy of learners' education records. This law sets limits upon the disclosure and use of these records without parents' or learners' consent. Some instances where schools are permitted to disclose these records are school transfers, cases of health or safety emergencies, and compliance with a judicial order.

FERPA also grants parents and learners over the age of 18 several rights over this information. These rights include the right to inspect these records, the right to request modification to inaccurate or misleading records, and more. Schools that fail to comply with these laws risk losing access to federal funding.

GLBA: The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), enacted by the United States Congress in 1999, establishes several requirements that financial institutions must follow to protect consumers' financial information. This law requires that institutions describe how they use and share information and allow individuals to opt-out in certain cases.

Like other cybersecurity laws, GLBA requires that financial institutions ensure the confidentiality and integrity of customer financial information by anticipating threats to security and taking steps to protect against unauthorized access. In addition, financial institutions must also describe the steps that they are taking to achieve this.

GDPR: The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a law adopted by the European Union in 2016 that regulates data privacy and security. It applies to the private sector and most public sector entities that collect and process personal data. It provides individuals with a wide set of rights over their data including the well-known "right to be forgotten" and other rights related to notifications of data breaches and portability of data between providers.

GDPR outlines a strict legal baseline for processing personal data. For example, personal data may be processed only if the data subject has given consent, to comply with legal obligations, to perform certain tasks in the public interest, or for other "legitimate interests". For businesses that process data on a large scale or for whom data processing is a core operation, a data protection officer - who is responsible for overseeing data protection - must be appointed.

GDPR also establishes an independent supervisory authority to audit and enforce compliance with these regulations and administer punishment for non-compliance. The fines for violating these regulations are very high: a maximum of 20 million Euros or 4% of revenue (whichever is higher), plus any additional damages that individuals may seek.

One unique aspect of GDPR is that it applies to any entity collecting or processing data related to people in the European Union, regardless of that entity's location. At the time of its adoption, it was considered the most strict data privacy law in the world and has since become a model for several laws and regulations enacted around the globe.

Key disclosure laws are laws that compel the disclosure of cryptographic keys or passwords under specific conditions. This is typically done as part of a criminal investigation when seeking evidence of a suspected crime. Several countries have adopted key disclosure laws requiring disclosure under varying conditions. For instance, Part III of the United Kingdom's Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA) grants authorities the power to force suspects to disclose decryption keys or decrypt data. Failure to comply is punishable by a maximum of two years in prison or five years if a matter of national security or child indecency is involved.

CCPA: The California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (CCPA) is a Californian law granting residents of the state certain privacy rights concerning personal information held by for-profit businesses. One of these rights is the "right to know", which requires businesses to disclose to consumers, upon request, what personal information has been collected, used, and sold about them, and why.

The "right to opt-out" also allows consumers to request that their personal information not be sold, something that must, with few exceptions, be approved. Another right is the "right to delete", which allows consumers to request that businesses delete collected personal information. In this case, however, some exceptions allow businesses to decline these requests.

3.5.2. Standards and Frameworks

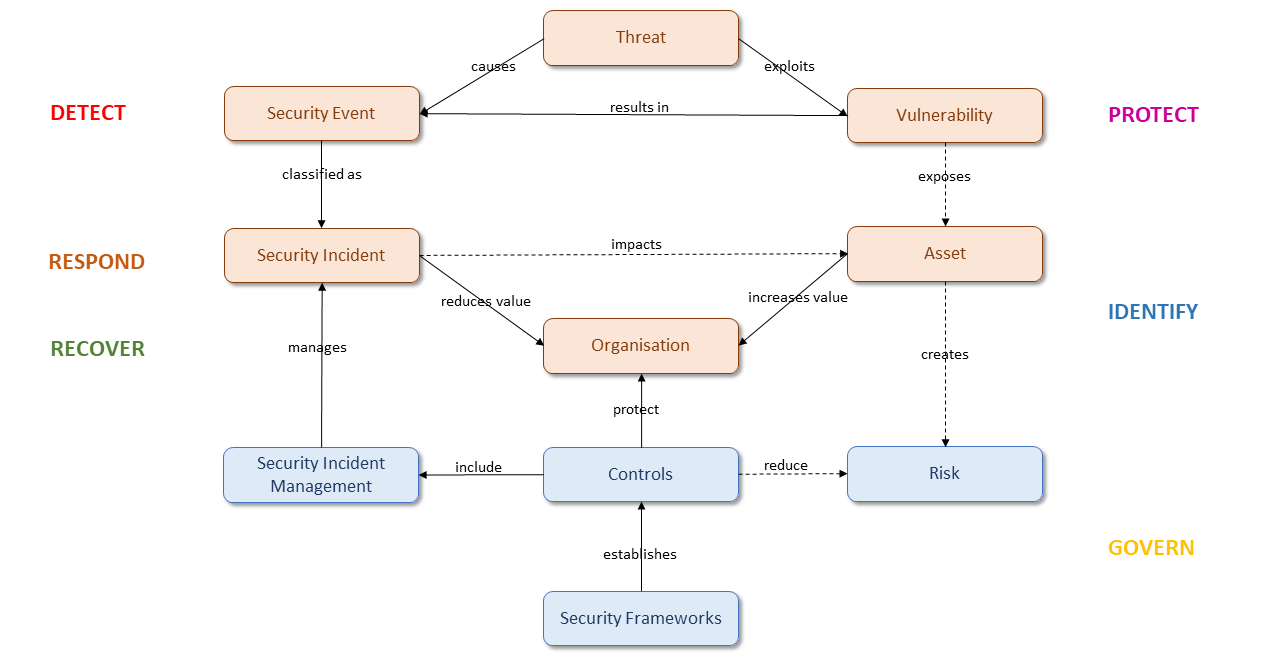

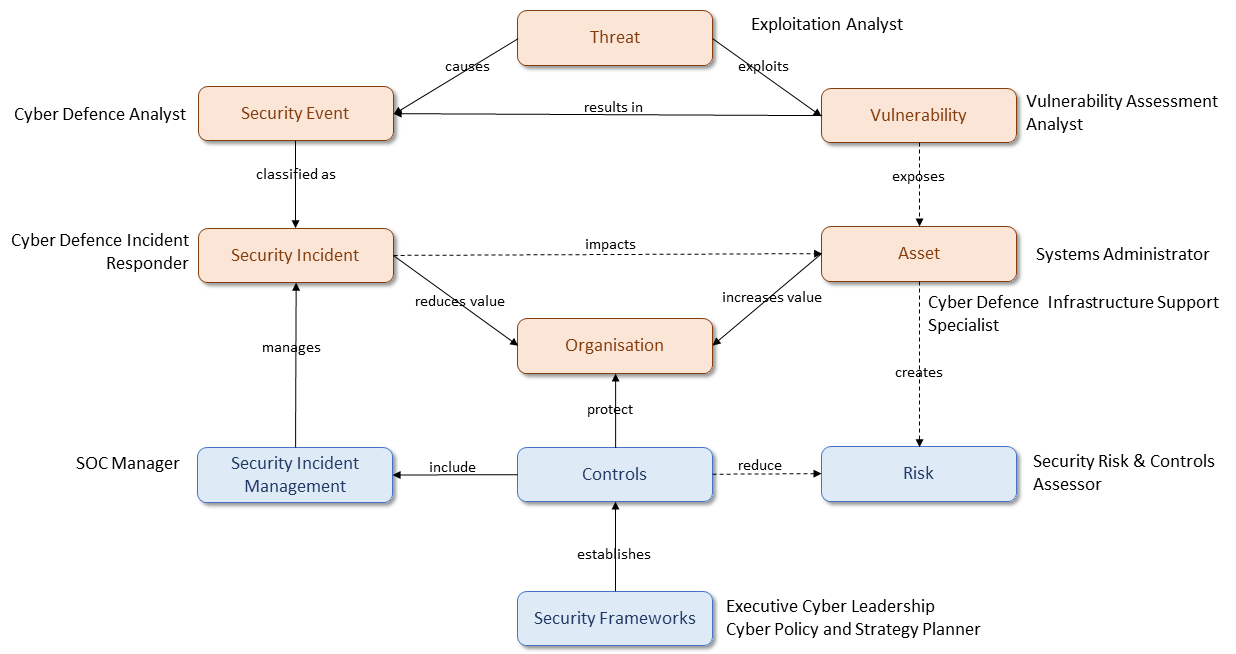

PCI DSS: The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) is an information security standard, first published in 2004, for organizations handling customer payment data for several major credit card companies. It is managed by the Payment Card Industry Standards Council. Its purpose is to ensure that payment data is properly secured to reduce the risk of credit card fraud. As with other frameworks, PCI DSS consists of several requirements and an organization's compliance must be assessed annually.